Ultrafast Delivery: The $28B Market to Build the On-Demand Bodega

Jan-Erik Asplund

Jan-Erik Asplund

This report contains company financials based on publicly available information and data acquired by Sacra during the preparation of the report. Sacra did not receive any compensation from any of the companies mentioned in the report. This report is not investment advice or an endorsement of any securities. Find our complete disclaimers at the bottom.

Shifting the demand curve

In 2005, Amazon transformed their business when they announced the launch of 2-day delivery with free shipping through a program called Prime.

Inside the company, teams feared the cost of the program would sink the company. Prices were so low that people were already saving money shopping on Amazon rather than driving to the store—now they were going to give away even more?

Of course, in the end, the cost of Prime shipping turned out to be far more than covered by the growth in customers and their frequency of purchase.

More people were buying, they were buying more frequently, and they were filling up their carts with more products. The company’s growth took off. Today, Prime has more than 200 million members and drives $25B a year in revenue.

Amazon’s big insight with Prime was the importance of speed in ecommerce.

Before, many Amazon customers had frugally waited until they had at least $25 worth of goods in their cart before checking out—which was the previous threshold to get free 2-day shipping. Prime created a sense of abundance and convenience that shifted the demand curve and opened the floodgates, clearing the way for rapid growth.

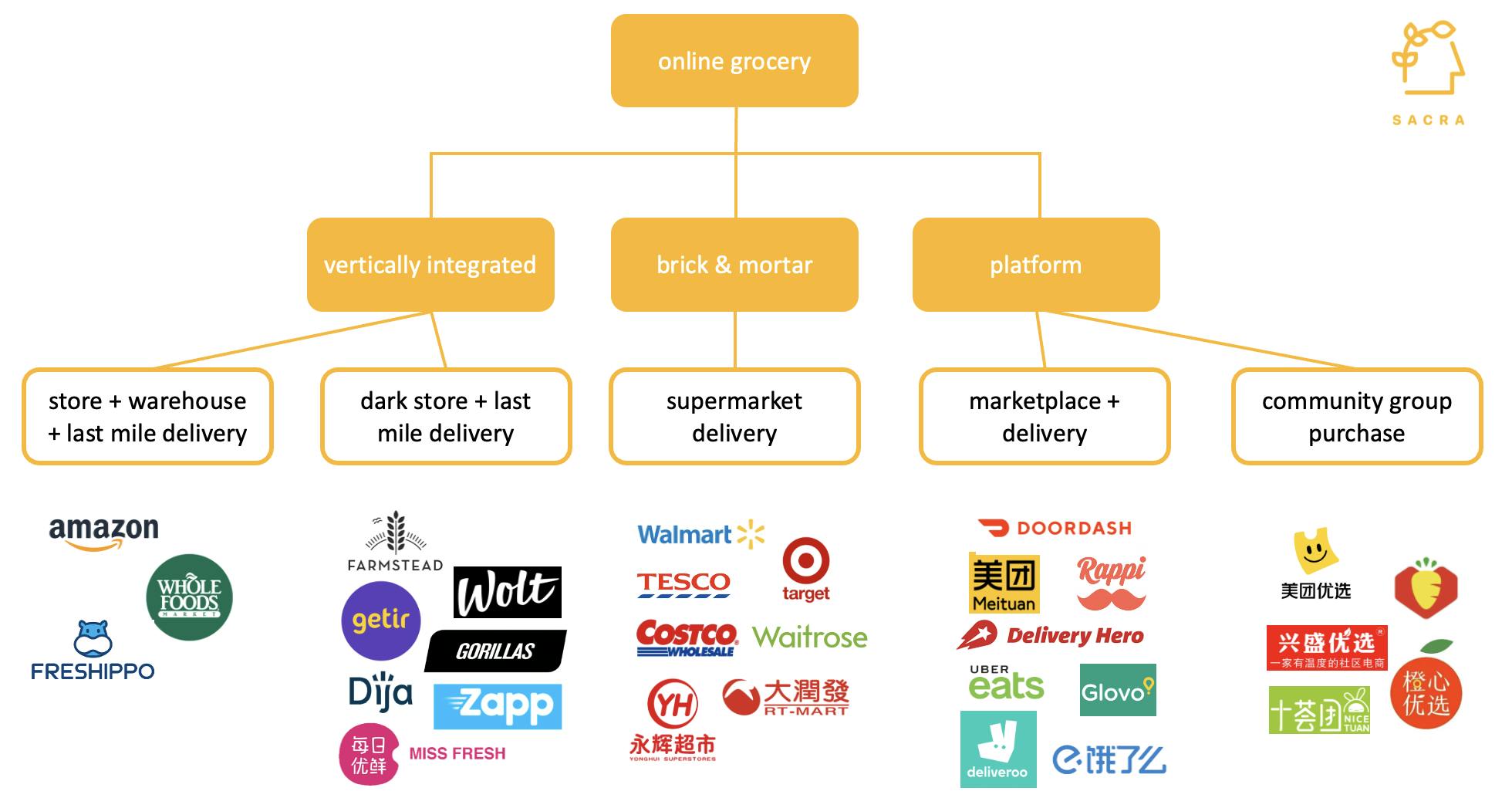

Today, there is a new crop of companies looking to push the envelope on shipping even further. Dark store-enabled, “ultrafast” delivery companies are getting funded and expanding across Europe, Asia, Russia, South America, and the United States.

Their big brand promise is 10 to 15 minute delivery—or "faster than you can," as the tag line for Gorillas goes—on grocery items.

With dark stores in densely populated urban areas on the back-end, and armies of delivery people on bikes and scooters for the last mile, they’re betting that delivering items in just 15 minutes can be as powerful a wedge as Amazon’s promise of two-day shipping was in 2005.

The strategy is largely out of the same playbook as other on-demand apps—capture customers, consolidate control over a high-frequency behavior, expand and cross-sell to other higher-margin categories. But their challenges are significant as well, from spoilage rates on grocery to hard-to-predict inventory requirements and building relationships with upstream suppliers.

Key points

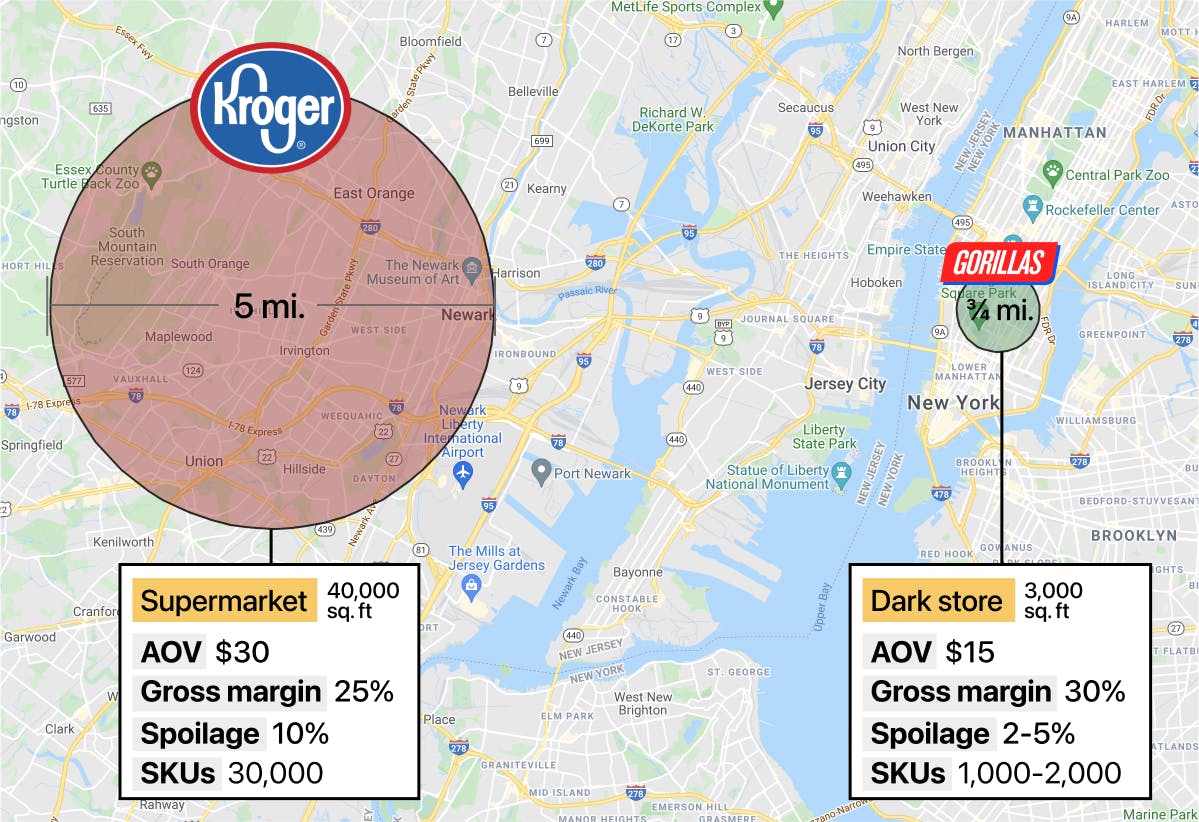

- Ultrafast delivery services operate out of 3,000~ square foot dark stores in urban core areas. That enables 10-15 minute delivery within their .75-1 mile service radius, as well as reducing supply chain costs and minimizing spoilage.

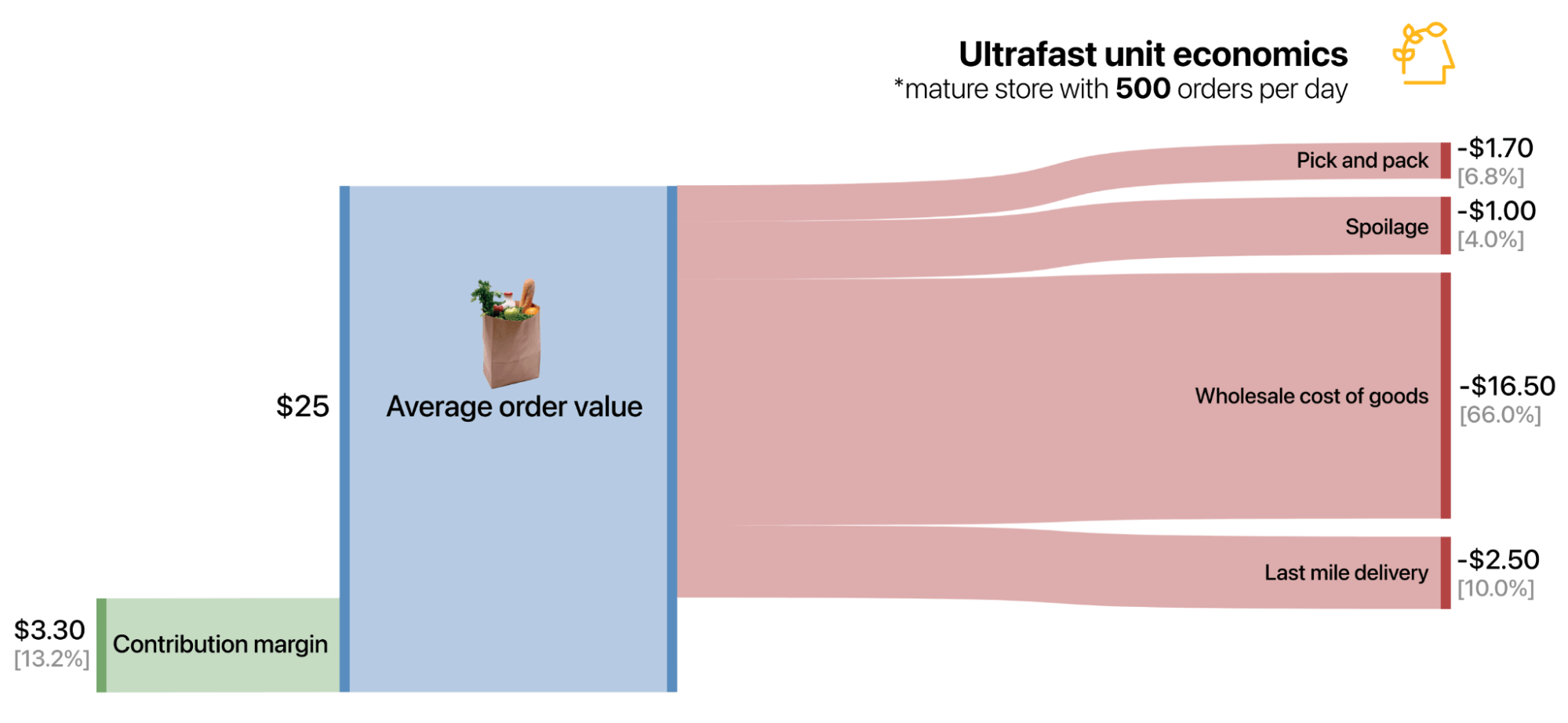

- Dark store profitability is measured with contribution margin, which excludes fixed costs. With $25 average order value in a mature ultrafast dark store with 500 orders per day, we project about 13% contribution margin.

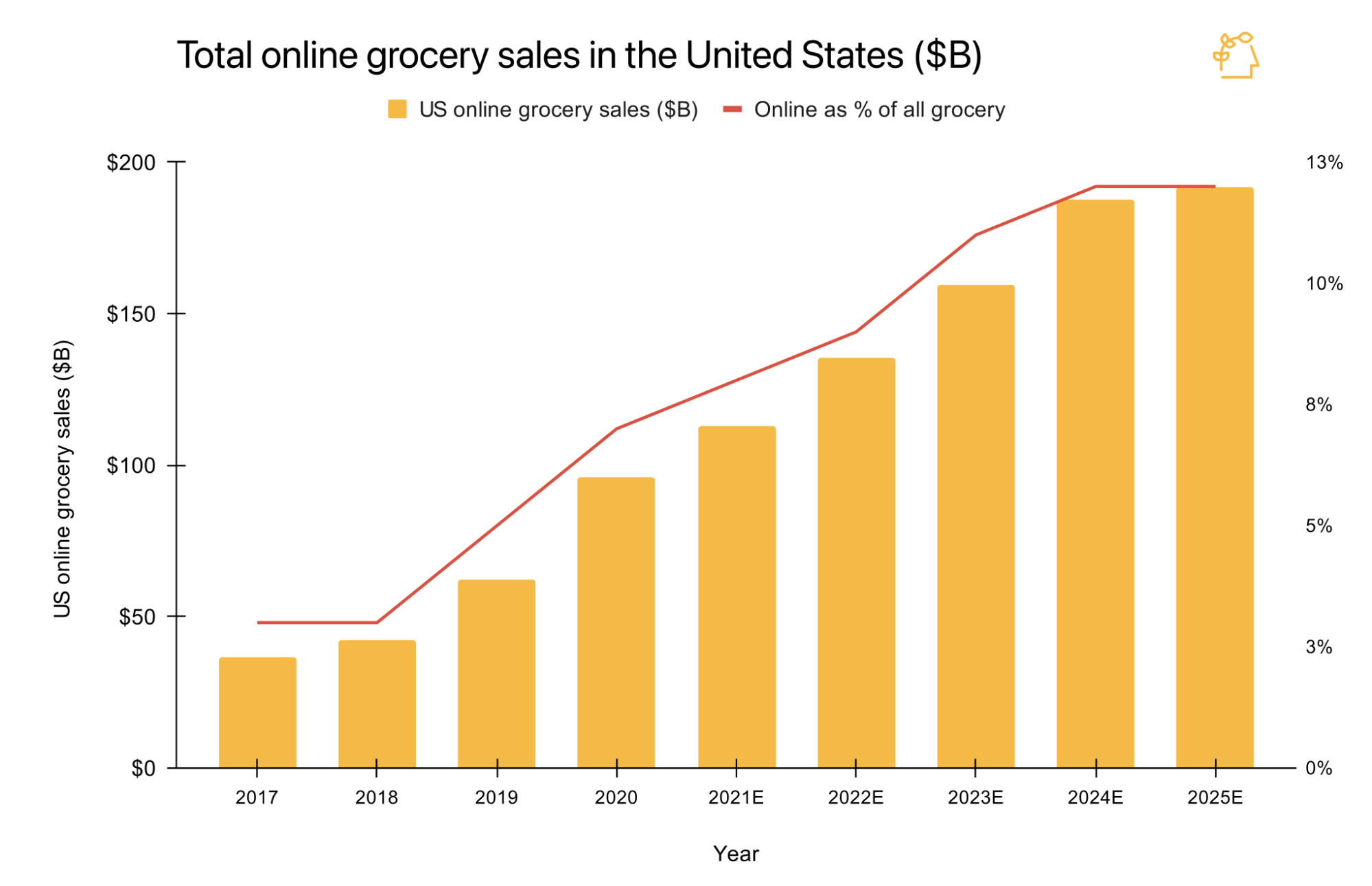

- In 2020, the growth of the online grocery market rapidly accelerated in the United States. The share of all grocery spending that took place online grew from 5% to 7%, with $96B in total online sales for the year up from $62B the previous year.

- We expect the total volume of online grocery sales in the U.S. to continue to grow, hitting $192B by 2025. 60% of people bought more groceries online during COVID and said they plan to buy groceries online at the same frequency or more often in the future

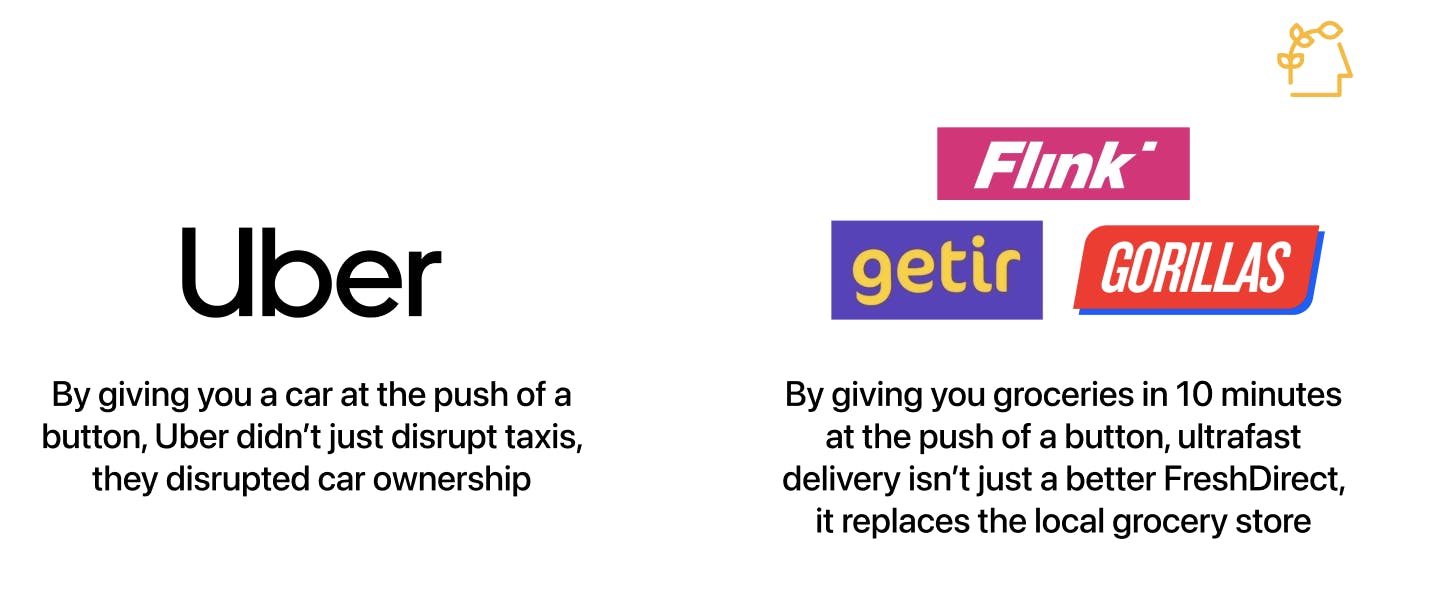

- The ultrafast vision is to replace the local grocery store the way Uber disrupted car ownership. By turning groceries into something summoned at the touch of a button rather than something planned and scheduled, ultrafast services want to change how we shop entirely.

- But the economics of ultrafast are hard, and micromobility is a cautionary tale. Both are capital-intensive industries with no customer loyalty, low switching costs, and limited network effects.

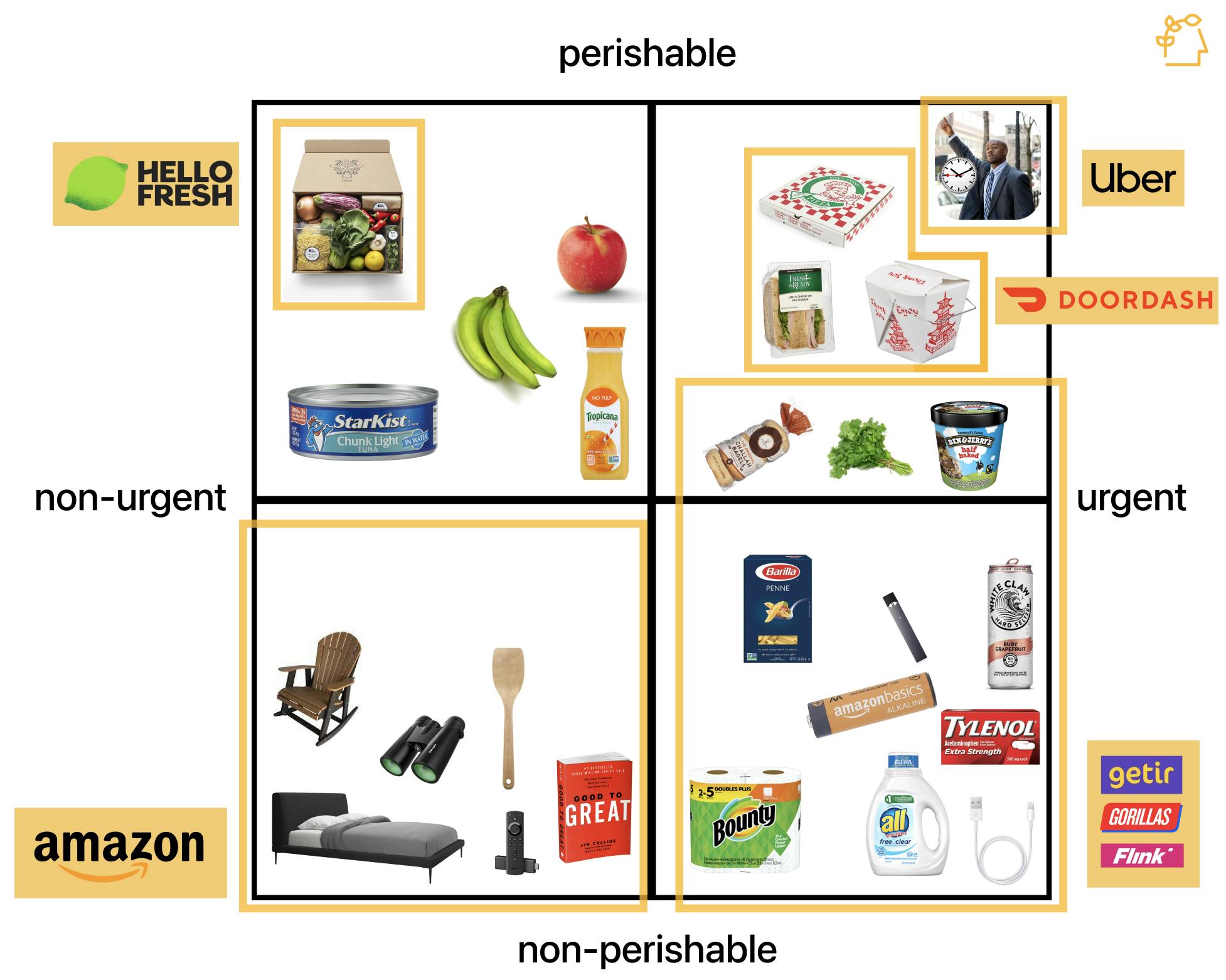

- Non-perishables with a high premium on fast delivery are where the ultrafast model makes most sense. Convenience store-type products like detergents, tobacco, phone chargers and grocery staples have low spoilage and consumers want to get them quickly, which fits the dark store model.

- Ultimately, CVS ($110B) and 7-Eleven ($42B) should be ultrafast's real targets, not Kroger ($28B) or Albertsons ($9B). Online grocery is a massive challenge both in logistics and demand generation, and ultrafast services are better off building a better convenience store than challenging for the whole of the online grocery market.

Business model: The internet-native online store

The Key Profitability Levers in Online Grocery

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

The Key Profitability Levers in Online Grocery

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

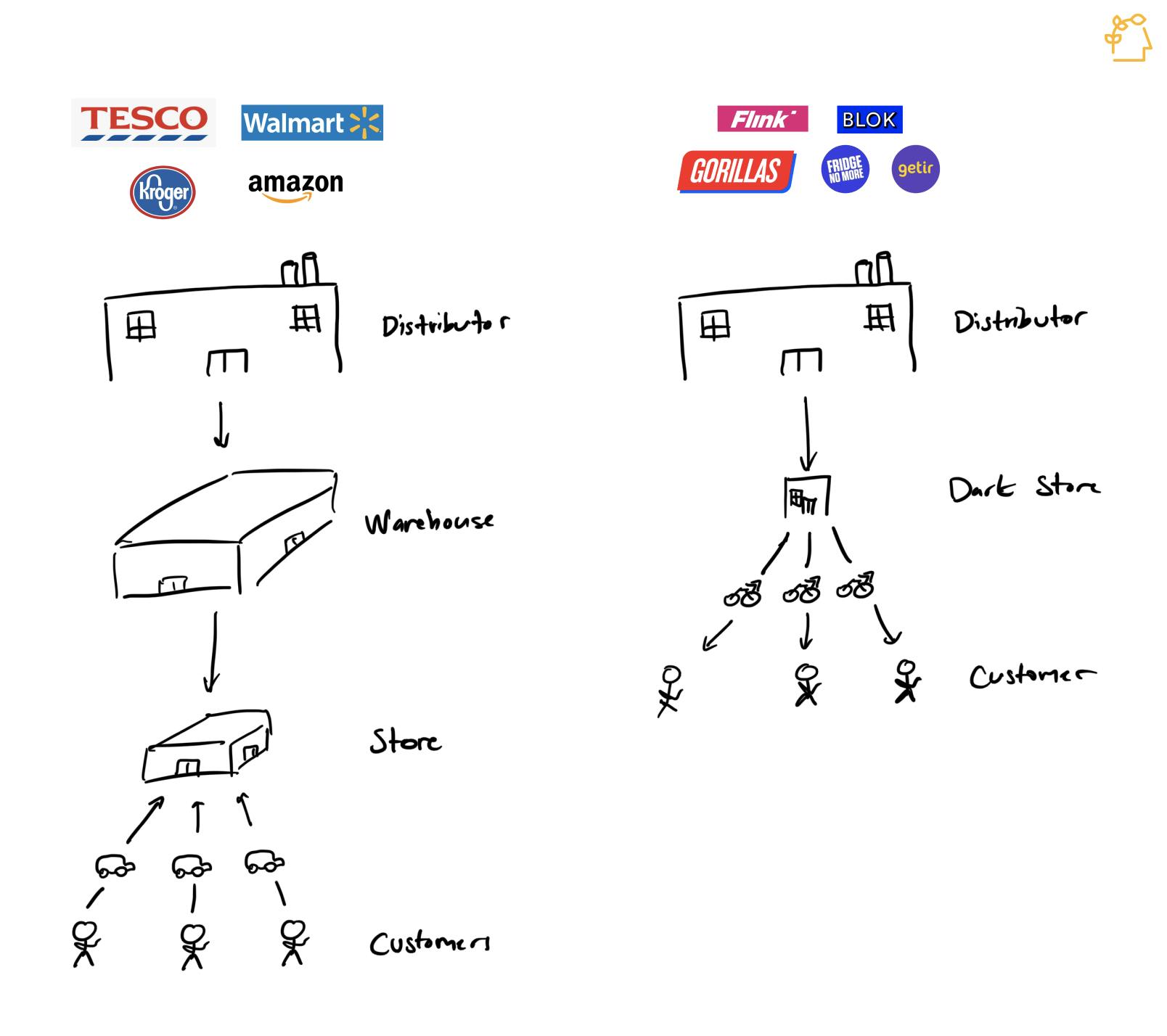

Ultrafast delivery services are stores that cut the intermediary out of the distributor-warehouse-supermarket supply chain, receiving inventory and fulfilling orders out of the same place.

These dark stores are located in dense, urban areas to facilitate super fast last-mile delivery, within 10-15 minutes. They’re also small—about 3,000 square feet—which means a limited range of SKUs.

Fleets of delivery workers utilizing scooters, bicycles, e-bikes and other micro mobility options pick up orders from these dark stores when customers order via app, and then deliver around the hub within a tightly limited radius of around a few miles.

Because the urban areas where ultrafast dark stores are located are dense, ultrafast services can make frequent deliveries, or drops. At 6x drops/hr, Getir’s claimed drop rate is higher than our estimation of 2x/hr for Deliveroo, 4x/hr for Dominos and 5x/hr for Farmstead.

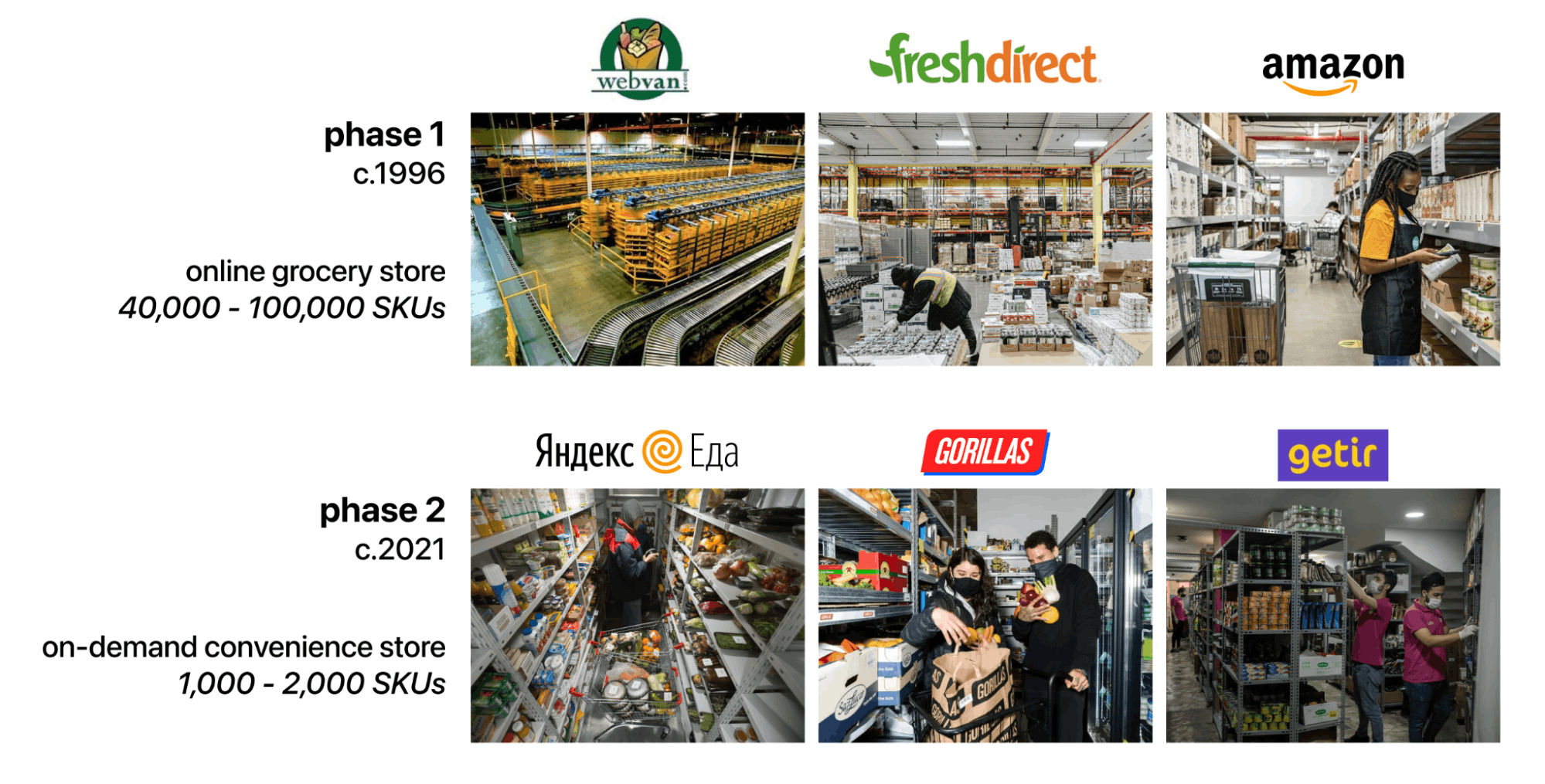

The trade-off is the small selection of items: Jokr, which is live in Mexico City, Lima, Sao Paolo, and New York, carries about 1,500 SKUs in each one of its dark stores, and most ultrafast delivery services have a similar range around 1,000 to 2,000. That’s in contrast to the 30,000 SKUs that might be available at a supermarket.

The challenge, as it is for all online grocery businesses, is finding a way to make the economics work given the costs: labor, inventory, spoilage, delivery, and so on.

Contribution margin is a measure of profitability that excludes fixed costs that don’t scale up with growth (administrative costs, etc.) instead only factoring in variable costs (e.g. paying for the staff at a dark store and delivery costs).

In the diagram above, contribution margin is calculated as it would be for an individual order from a hypothetical mature dark store with 500 orders per day: average order value less spoilage, cost of goods, labor and delivery. Depending on the resolution at which you want to understand the business, you might also deduct either rent or cost of customer acquisition:

- Cost of customer acquisition: Brick-and-mortar grocers have built in geographical demand, but online grocers must pay “rent” to Google, Facebook and other top-of-funnel acquisition tools—and that rent tends to rise over time

- Rent: Rent is traditionally a fixed cost but could be a variable cost in online grocery, if scaling up your volume and growing geographically means you might need more packing and storage space per store, so it could be deducted if looking at store-by-store contribution margin

Looking at the economics of online grocery through the lens of contribution margin rather than mere gross margin means a better picture, at least early on, of whether a company’s core unit economics are profitable. A loss-making company with a good contribution margin—assuming those fixed costs truly don’t scale up with growth—can eventually grow into true profitability.

A loss-making company with a negative contribution margin still has work to do, either to increase the size of the average customer basket or reduce how much it costs to procure the items.

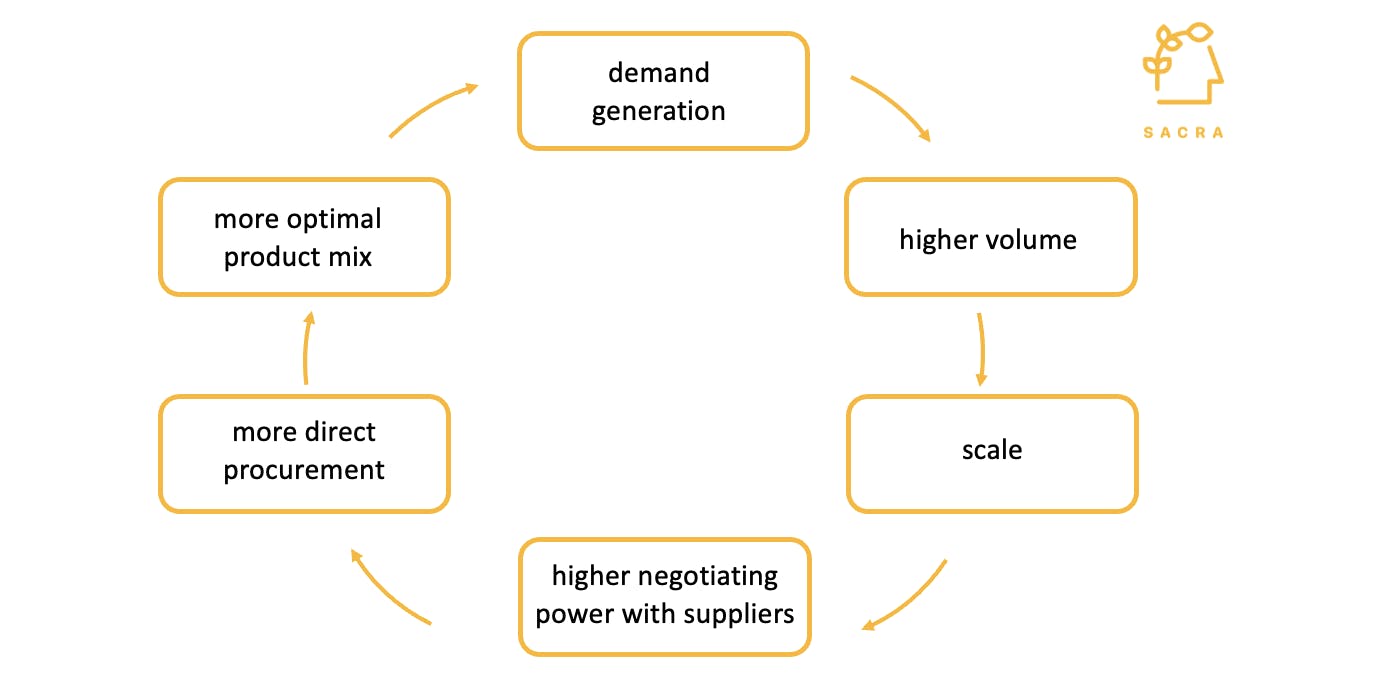

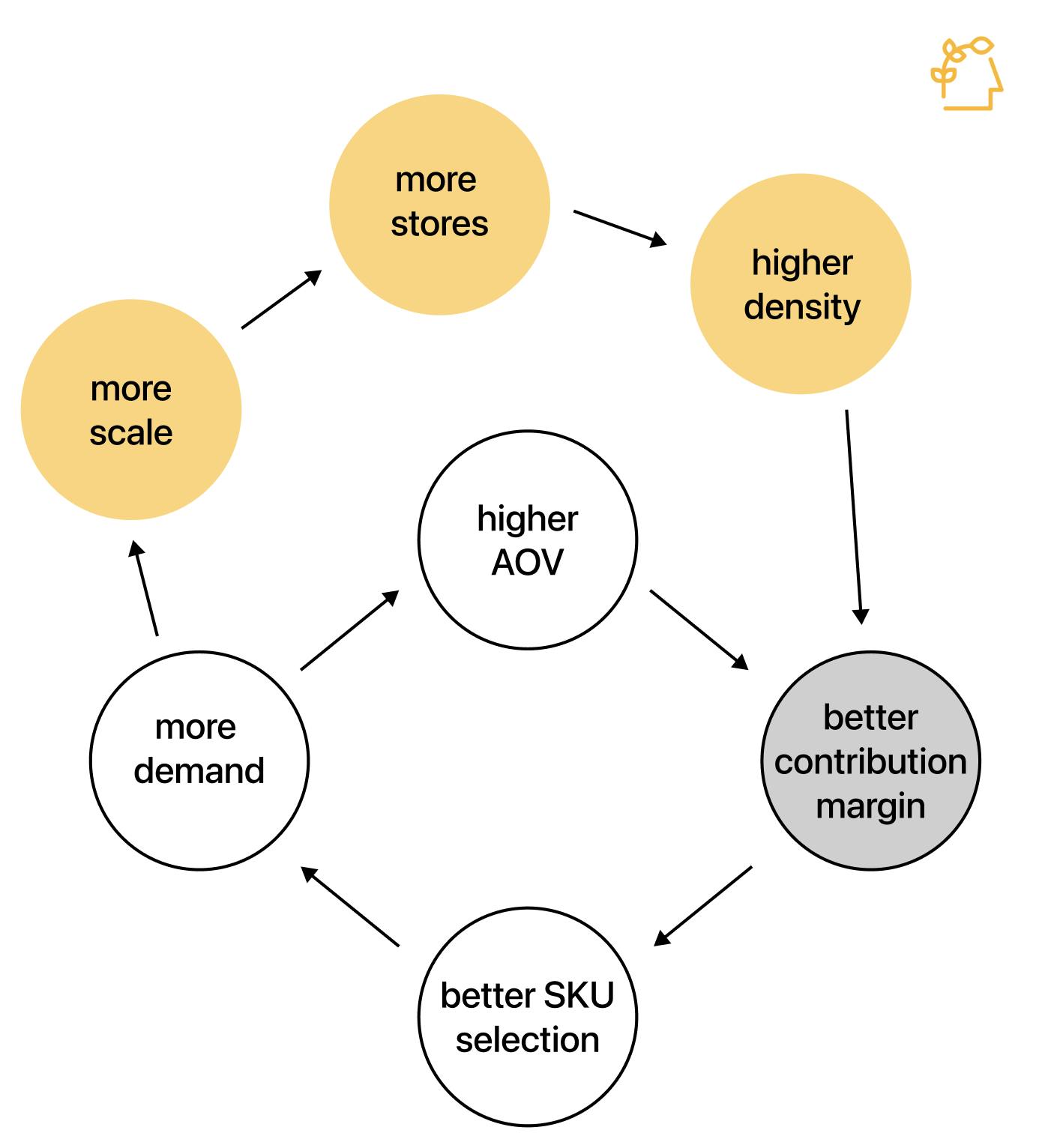

This is why there are two core levers for any online grocery business, including ultrafast delivery services:

- Growing AOV: By aggregating more demand and selling more SKUs, services increase the value of the average customer basket and get closer to a sustainable business

- Improving gross margin: Through things like moving towards direct procurement, using data to reduce spoilage and optimizing product mix, services can cut down distribution costs and improve their economics

Ultrafast’s simplification of the grocery supply chain, with inventory being received, stored, and delivered from the same dark stores, helps reduce costs and spoilage—for them, growing AOV can be a bigger problem given the smaller basket sizes typical of on-demand services and the challenge of competing with other services for demand.

TAM: On-demand grocery is growing 25%+ CAGR

Online Grocery Unit Economics, Sensitivity Analysis and TAM

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

Online Grocery Unit Economics, Sensitivity Analysis and TAM

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

In 2020, the growth of the online grocery market rapidly accelerated in the United States. The share of grocery spending that took place online grew from 5% to 7%, with $96B in total online sales for the year, up from $62B the previous year.

While we expect growth to slow to c.15% 3-year CAGR, we expect the total volume of online grocery sales to continue to grow, hitting $192B by 2025, and we expect the total proportion of grocery spend that is online to grow to 12%.

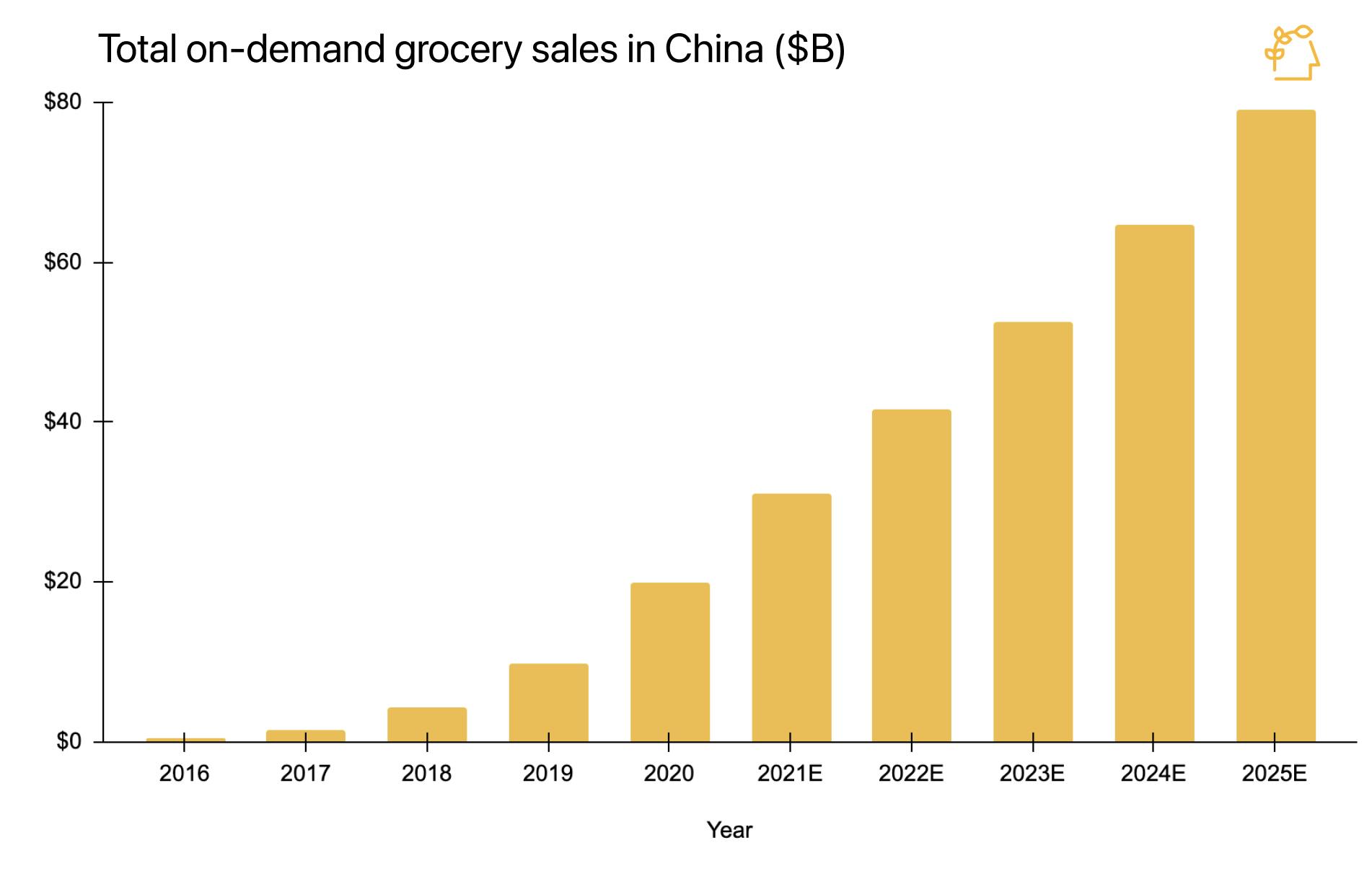

On-demand grocery delivery GMV can serve as a useful proxy for understanding the future of the ultrafast category.

Looking at some indicators from China, on-demand grocery and daily necessities—encompassing services that deliver perishables and non-perishables in anywhere from between 20 minutes and 1 hour—grew 106% YoY in 2020, reaching $20B GMV. That brought it to 6% of all online grocery sales, up from 4% the year before.

We expect the on-demand delivery category to continue to grow at 25%+ CAGR, with ultrafast delivery services growing faster, particularly as they expand into under-penetrated urban American markets:

- In China: We project that on-demand grocery and daily necessity spend will hit $80B by 2025, about 10% of online grocery spend and 3.5% of all grocery spend

- In the United States: With online grocery sales hitting $192B by 2025, we expect on-demand online grocery spend to hit a 15% share of that total, or about $28B in total

Ultrafast could represent as much as a third of that spend on on-demand online groceries. While the primary ultrafast delivery services (today) are designed to operate in urban centers, In the United States, just 31 urban or urban-adjacent counties represented 32.3% of the country’s gross domestic product in 2018.

Analysis: How ultrafast services are building the convenience stores of on-demand

The first online grocery services—Peapod, Webvan, Kozmo, FreshDirect, as well as early iterations of Amazon Fresh—made the mistake of thinking that they needed to stock everything that you would find in a traditional grocery store. They stocked tens of thousands of SKUs, many of them perishables, and found that they incurred huge amounts of waste as a result.

Their problem was that they didn’t have the demand to back up the incredible amounts of supply that they were accumulating in their warehouses.

The ultrafast delivery services take the opposite approach. Instead of stocking themselves like a grocery store and then setting out to find customers, they stock a 3,000 square foot dark store with a few thousand SKUs and aim to generate demand via hyperlocal advertising, digital marketing, and a novel value proposition: necessities and groceries delivered in 10 minutes.

Pradeep Elankumaran, CEO of Farmstead, on the future of online grocery

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

Pradeep Elankumaran, CEO of Farmstead, on the future of online grocery

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

1. The COVID-fueled rise of everything on-demand

New data from American shoppers suggests that the trend from offline to online grocery shopping—accelerated by COVID—will not slow down or give up its gains in the years to come.

In the United States:

- 60% of people bought groceries online between April 2020 and April 2021—up from 52% a year before

- 60% of those people said they plan to buy groceries online at the same frequency or more often in the future

As buying groceries online becomes increasingly normalized, ultrafast delivery services are betting that they can win customers by offering a value proposition similar to Uber’s when it first launched.

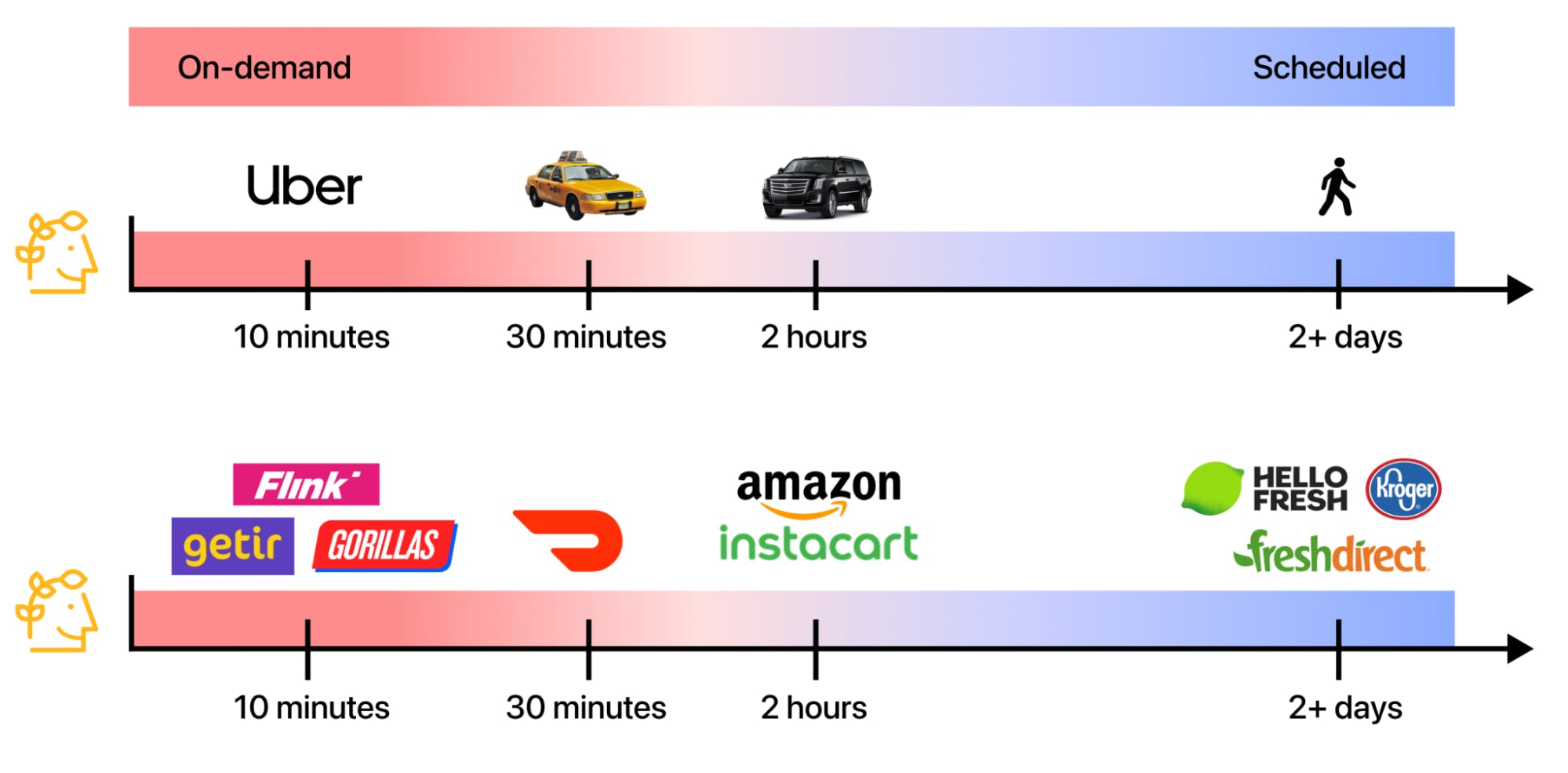

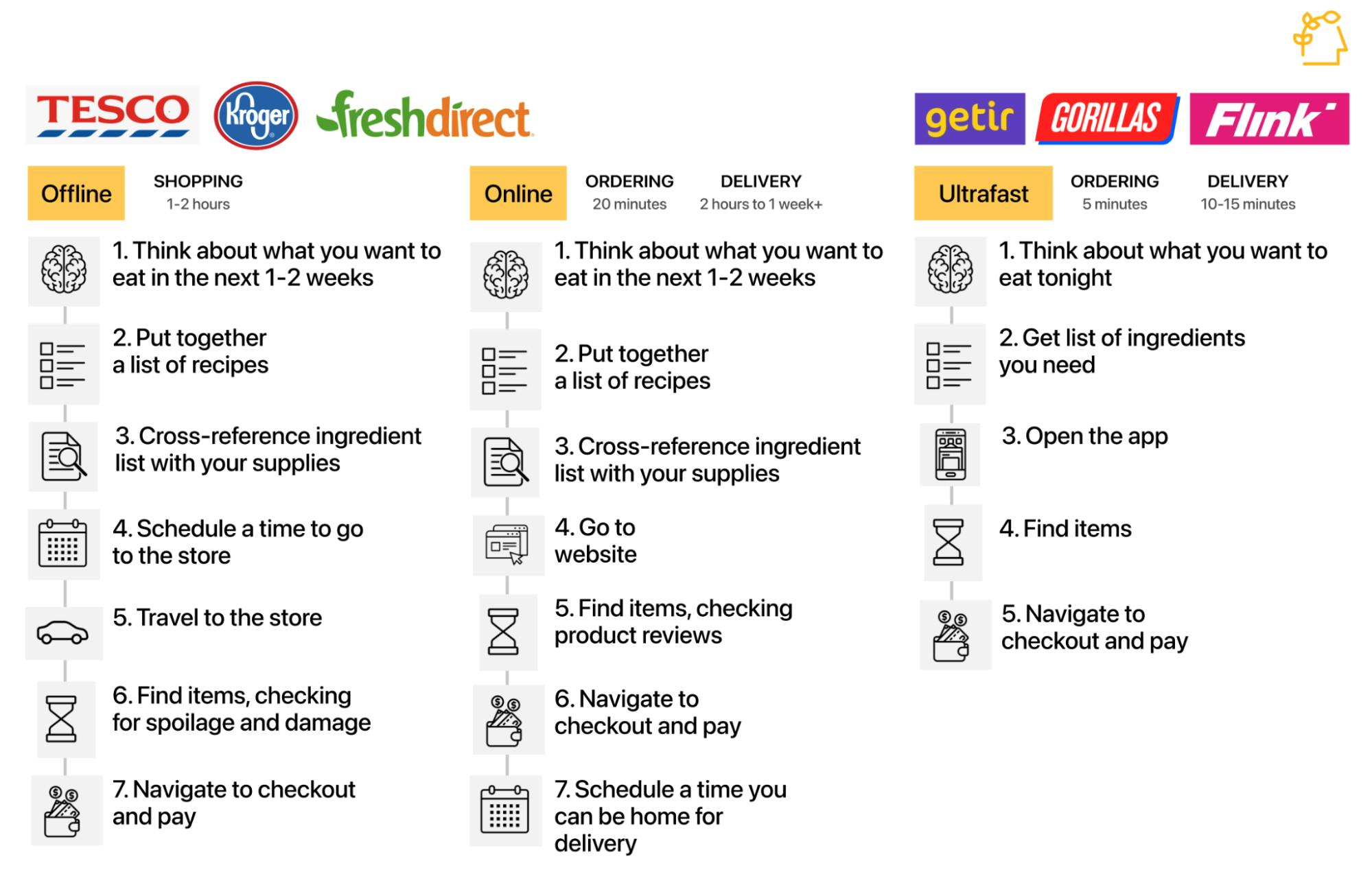

Ultrafast delivery presents a spontaneous and truly on-demand alternative to the two dominant modes in grocery today:

- Brick-and-mortar (Kroger, Albertsons): Plan out what meals you want to eat and what ingredients you need, schedule a time to go to the store, take a car or train/bus, shop, and then load up your groceries and haul them home

- Online (Instacart, Amazon Prime): Plan out what meals you want to eat and what ingredients you need, schedule a window for your delivery, shop, and then respond to substitution requests from your packer while waiting at home for your delivery person

Ultrafast services promise something like the magic moment that put Uber on the map. With Gorillas or Getir or Flink, you don’t have to think about what you may eat in the days ahead, what you need to buy, or find a time that you’ll be home to receive your order. There are no substitution requests. Instead, you get home from work, think about what you might want and tap some buttons in an app. 10-15 minutes later, groceries that you could never have previously acquired in 10-15 minutes arrive on your doorstep.

Uber felt magical when it first launched because it connected an asset—for-hire car drivers—that were being underutilized, driving around idle looking for fares when they could have been picking up people nearby. By connecting those drivers to passengers through an app, Uber enabled faster pick-up times than were possible with any taxi or car service.

While Instacart and DoorDash and Amazon (and Uber) offer 1st and 3rd-party grocery delivery today, none deliver faster than you can.

This Uber-like, touch-button service also removes a cognitive barrier to delivery, helps eliminate the problem of abandoned carts, and enables usage on the order of 1-2x per day rather than 1-2x per month as you might see with a traditional same or next-day online grocery service.

The real upside is not just fast delivery but how fast delivery streamlines the process of eating.

You no longer have to schedule when you can make it to the store to do your bulk buy, manage your fridge’s inventory of produce and fruits so that things don’t go bad and rot, or make a plan of all the ingredients you need to buy for all the recipes you plan to make.

The same way it was thought that Uber could go from an alternative to taxis to replacing the personal automobile, the bullish take on ultrafast delivery startups is that they can go from an alternative to conventional online grocery services to replacing your local grocery store entirely.

And as they do, they have a chance to shift the demand curve the same way Amazon or Uber did. Uber's taxi alternative grew the larger for-hire car market because it made for-hire cars an option in more types of circumstances, while Amazon's free shipping deal made ecommerce an attractive option for more kinds of purchases. While the on-demand online grocery market today is only a percentage of the online grocery market, which itself only represents 7% of all grocery sales in the U.S, a big part of the thesis around ultrafast is that shifting grocery from a scheduled to a touch-button purchase could expand the market in a similar way.

2. How ultrafast delivery services could end up the electric scooters of 2021

Whether the ultrafast business model with its 10-15 minute delivery is sustainable is yet to be seen.

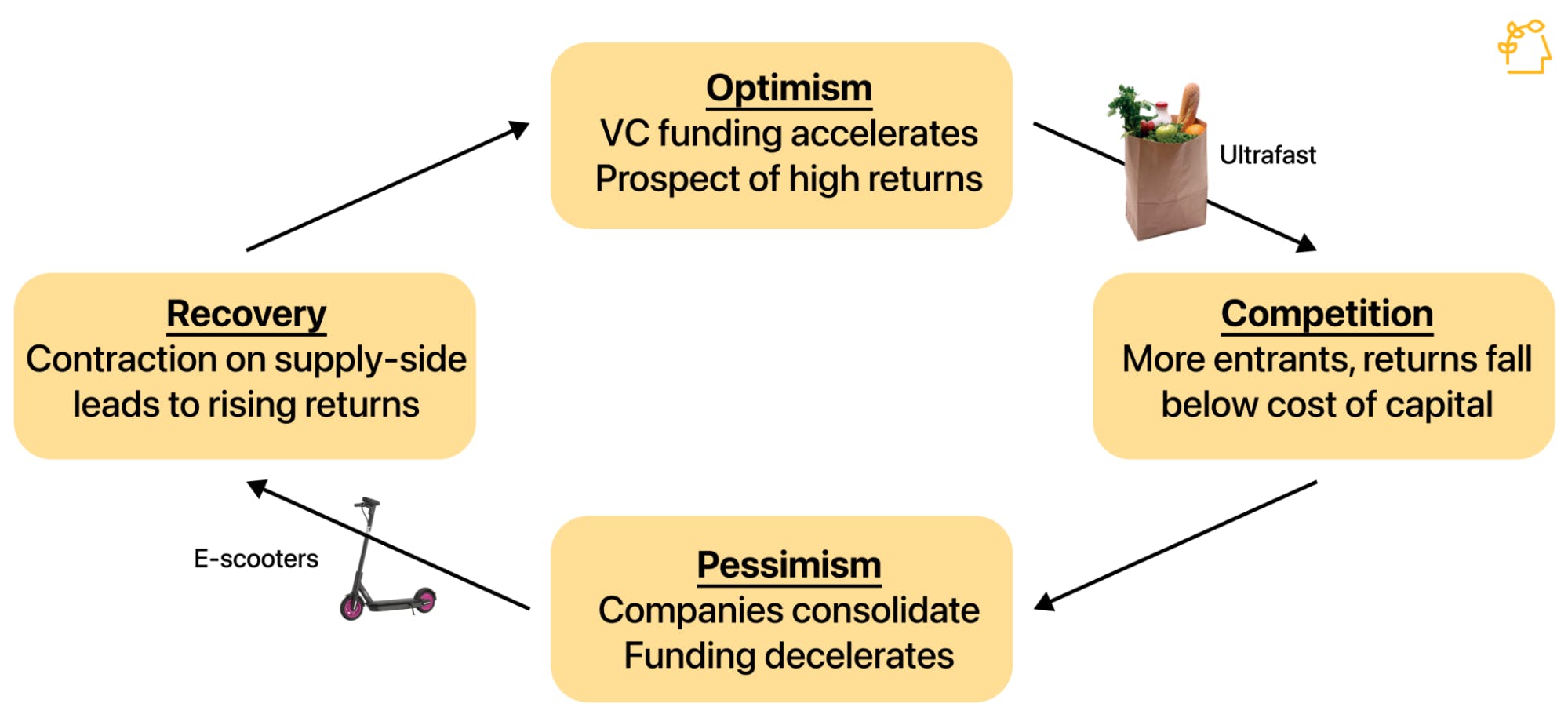

Here, bike and scooter sharing is a cautionary tale. Both bike and scooter sharing and ultrafast delivery are capital-intensive industries with no customer loyalty, low switching costs, and limited network effects. The unit economics are unproven, and while optically high, growth could be short-lived.

Out of the four stages in the classic capital cycle, ultrafast delivery services are just in or emerging out of the first, while e-scooters are currently emerging from the third:

- Optimism: First, there is a period of exuberant financing, expansion, and investor optimism

- Competition: Then, there is rising competition, new companies, and the tightening of returns

- Pessimism: Consolidation of the industry occurs, with most players folding or getting acquired for cheap

- Recovery: Finally, recovery and strengthening of economics as supply-side improves

The micro-mobility industry took off with the launch of Bird and then Lime, but within just a few years, unprecedented investor optimism gave way to a sobering reality-check:

- Optimism: Bird became the fastest-ever startup to unicorn status, getting to $1B in 6 months and $2B in a year. 10M Bird rides were taken in its first year after launch.

- Competition: The popularity of micro-mobility caused the floodgates to open, and 30+ e-scooter startups would go on to be founded in the year after Lime and Bird became unicorns.

- Pessimism: In 2019, Lyft turned off its scooter business in 6 cities, and last year, Uber offloaded its bike and scooter business to Lime in a deal that cut Lime’s valuation by 80%.

- Recovery: COVID brought some signs of a recovery, with Bird planning to go public via SPAC at a $2.3B valuation and Ford mulling a spin-off of Spin.

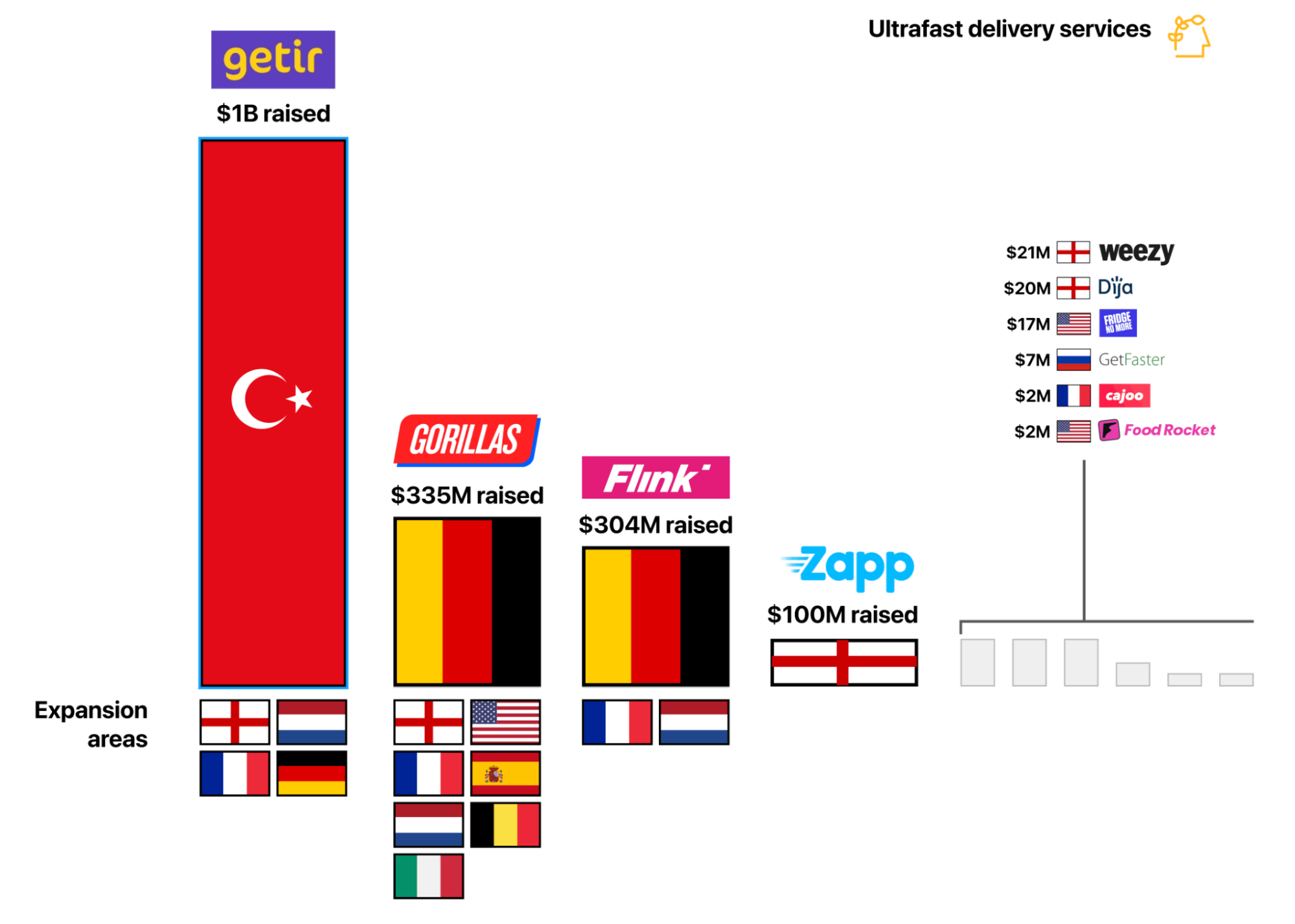

In ultrafast, the optimism is there. Between March 2020 and April 2021, all on-demand grocery services raised $14B in VC. The Turkish company Getir alone has raised a total of $1B, while Gorillas—which has expanded from Germany to 7 countries including the United States, has raised $335M.

The problem is that without generating a positive contribution margin per order, a higher frequency of order—as ultrafast delivery services are designed to promote—just means companies burning cash at a faster rate, making it hard not just to sustain the business, but potentially to raise more capital later.

This is part of what happened to e-scooters come 2019: one company, Scoot, found itself selling to Bird for just $25M after being valued at $71M because it was unable to raise enough capital to keep going. Lime had to accept an 80% valuation cut after racking up losses of more than $300M, and more recently, Bird itself had to lay off 400 employees.

And the on-demand grocery space has plenty of major challenges for ultrafast providers to overcome:

- Managing the supply chain and negotiating with suppliers: To improve their unit economics at scale, ultrafast delivery operators will need the understanding of the supply side and how to bring down their cost basis

- Potentially high fresh food spoilage rates: As they increase scale, ultrafast operators will grow their waste, hurting their unit economics unless they can optimize inventory

- Varied inventory requirements: Due to differences in consumers in each area, differences in category demand can increase operational complexity.

Our research shows us that an AOV of about $50 is what the average online grocery service needs to be profitable, and for a service predicated on smaller purchases, that may be a tough milestone.

To get their costs down and eke out a profit, traditional, high-volume grocery operators negotiate extensively with distributors and producers. Many ultrafast delivery services are helmed by teams with experience running other on-demand services and generating demand, but this supply side skillset is just as vital.

And if consumer demand for ultrafast delivery does turn out to be genuine and durable, the ultrafast startups will suddenly be competing with behemoths like Kroger, Tesco, and Amazon that have that supply side skillset and are an army of bike couriers away from having virtually the same last-mile capacity. And some of those companies are already eyeing the market, with both Amazon and DoorDash being rumored to be pursuing acquisitions of ultrafast services in Europe.

Amazon is already moving in this direction itself:

- In New York, users can select a 30-minute pickup option for groceries being picked up from Whole Foods

- By 2022, Amazon plans to have eleven new micro-fulfillment centers launched that will deliver a range of 100,000+ SKUs within 45 minutes in Seattle, DC, Baltimore, Dallas, Nashville, Detroit, Chicago, San Diego, and Phoenix

Meanwhile, Instacart announced recently that it was rolling out 30-minute "Priority Delivery" in fifteen cities including Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, San Diego, San Francisco, and Seattle.

If ultrafast delivery services flame out, it will most likely be because despite their popularity and value proposition, they cannot make the unit economics sustainable. What will happen instead is that existing players in grocery will leverage their existing infrastructure of stores and warehouses or acquiring an ultrafast player at a discount to buy their customer base.

Like what happened in e-scooters, we’ll see smaller players fold or get acquired on the cheap—either by other private market ultrafast companies or by incumbents—with 1 or 2 standout deals and no outright winners.

3. Why ultrafast’s biggest targets may be CVS ($110B) and 7-Eleven ($42B), not Kroger ($28B) and Albertsons ($9B)

Ultrafast delivery services have a highly compelling value proposition: a range of SKUs, from fresh fruits and vegetables to laundry detergent, soap, and toilet paper, delivered to your front door in 10 minutes.

They also face, as we discussed in the previous section, some serious challenges around making the economics of online grocery sustainable.

That’s why we believe that the path forward for Gorillas, Getir, Fridge No More and other ultrafast delivery services is not to try to beat the existing online grocers at their own game, but to instead double-down on the kinds of SKUs where their model fits best: non-perishables with a high premium on fast delivery.

Ultrafast delivery services aren’t well-positioned to take on Kroger or Albertsons or Amazon, which have the scale, supply chains, and deep logistics experience necessary to deal with large volumes of both perishables and non-perishables.

On the non-perishable side, however, the ultrafast delivery services have big advantages:

- The dark store model: Their dark store-based model and emphasis on micro-mobility for delivery allows them to be faster and more consistent than marketplace platforms like Drizly or Uber Eats

- Specificity on job-to-be-done: Running apps that are just for 10-15 minute delivery of non-perishables means that ultrafast services can become top of mind for consumers, carving out a wedge they can own against other services

Ultrafast delivery services don’t just recreate the convenience of a 7-Eleven or a gas station or pharmacy, offering rapid delivery on items like phone chargers, trash can liners, shampoo, razors, and other similar deliverable goods where speed is paramount—they do it better.

When you realize you’re missing an HDMI cable to get your new television hooked up or you need a new phone charger before you leave for a trip, 2-hour same-day delivery from Amazon isn’t fast enough. Driving or biking to a convenience store in 10-15 minutes is fast, but getting delivery in 10-15 minutes is better because it doesn’t require time spent hunting items down in a store, or return travel.

For the ultrafast services, dealing almost exclusively in non-perishables—with choice perishables added in to find the right product mix—means:

- No or minimal spoilage: Stocking like a grocery store, as the early online grocery warehouses discovered, means experiencing waste and spoilage like a grocery store

- Potential to driver higher AOV: Non-perishable electronics, cosmetics, alcohol, and others can have a high dollar value, and cross-selling between these kinds of categories can create a viable product mix for maximizing AOV

As far as what that product mix should be, the ultrafast services should look at bodegas. While Gorillas isn’t likely to start taking your packages or looking after your apartment’s spare key, NYC bodegas have figured out the Lindy product mix necessary to sustain a 3,000 square foot convenience store with a few thousand SKUs in urban cores. While neighborhood differences create some variation between bodegas (particularly in the selection of prepared food and the variety of "healthy options" on offer) virtually every bodega follows the same timeless formula:

- Staples: Chips, candy, sodas, coffee, cigarettes, gum, vapes, lottery tickets, etc.

- Household: Shampoo, razors, body wash, soap, laundry detergent, dryer sheets, lip balm, etc.

- Tech: Earbuds, iPhone and Android phone chargers, HDMI cables, etc.

- Fresh: Bananas, apples, lettuce, limes, lemons, avocados, etc.

- Prepared: Muffins, bagels, sandwiches made to order, juices, smoothies, etc.

- Miscellaneous: Frisbees, staplers, leashes, candles, etc.

If ultrafast services can drive demand and figure out the product mix, there’s a simple pathway to growth:

- Opening up more dark stores grows their geographical service area, increasing their density and volume of purchasing

- More volume means more SKUs and larger scale to directly procure items from suppliers, creating a better contribution margin

- Better contribution margin means services are more profitable, which enables them to grow and open up new stores faster

This is why the ultrafast delivery startup’s real target should not be the grocery store, but companies built on convenience like CVS ($110B) and 7-Eleven ($42B).

Appendix

Disclaimers

- Sacra has not received compensation from any companies that are subjects of the research report.

- Sacra generally does not take steps to independently verify the accuracy or completeness of this information, other than by speaking with representatives of the companies when possible.

- This report contains forward-looking statements regarding the companies reviewed as part of this report that are based on beliefs and assumptions and on information currently available to us during the preparation of this report. In some cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by the following words: “will,” “expect,” “would,” “intend,” “believe,” or other comparable terminology. Forward-looking statements in this document include, but are not limited to, statements about future financial performance, business plans, market opportunities and beliefs and company objectives for future operations. These statements involve risks, uncertainties, assumptions and other factors that may cause actual results or performance to be materially different. We cannot assure you that any forward-looking statements contained in this report will prove to be accurate. These forward-looking statements speak only as of the date hereof. We disclaim any obligation to update these forward-looking statements.

- This report contains revenue and valuation models regarding the companies reviewed as part of this report that are based on beliefs and assumptions on information currently available to us during the preparation of this report. These models may take into account a number of factors including, but not limited to, any one or more of the following: (i) general interest rate and market conditions; (ii) macroeconomic and/or deal-specific credit fundamentals; (iii) valuations of other financial instruments which may be comparable in terms of rating, structure, maturity and/or covenant protection; (iv) investor opinions about the respective deal parties; (v) size of the transaction; (vi) cash flow projections, which in turn are based on assumptions about certain parameters that include, but are not limited to, default, recovery, prepayment and reinvestment rates; (vii) administrator reports, asset manager estimates, broker quotations and/or trustee reports, and (viii) comparable trades, where observable. Sacra’s view of these factors and assumptions may differ from other parties, and part of the valuation process may include the use of proprietary models. To the extent permitted by law, Sacra expressly disclaims any responsibility for or liability (including, without limitation liability for any direct, punitive, incidental or consequential loss or damage, any act of negligence or breach of any warranty) relating to (i) the accuracy of any models, market data input into such models or estimates used in deriving the report, (ii) any errors or omissions in computing or disseminating the report, (iii) any changes in market factors or conditions or any circumstances beyond Sacra’s control and (iv) any uses to which the report is put.

- This research report is not investment advice, and is not a recommendation or suggestion that any person or entity should buy the securities of the company that is the subject of the research report. Sacra does not provide investment, legal, tax or accounting advice, Sacra is not acting as your investment adviser, and does not express any opinion or recommendation whatsoever as to whether you should buy the securities that are the subject of the report. This research report reflects the views of Sacra, and the report is not tailored to the investment situation or needs of any particular investor or group of investors. Each investor considering an investment in the company that is the subject of this research report must make its own investment decision. Sacra is not an investment adviser, and has no fiduciary or other duty to any recipient of the report. Sacra’s sole business is to prepare and sell its research reports.

- Sacra is not registered as an investment adviser, as a broker-dealer, or in any similar capacity with any federal or state regulator.