The Key Profitability Levers in Online Grocery

Nan Wang

Nan Wang

The last e-commerce battleground

Strict requirements for cold chain logistics, food spoilage and a lack of standardization have historically constrained how much grocery can move online. Nevertheless, increasing focus and firepower have been dedicated to this space over the last year due to COVID tailwinds, changing consumer purchasing habits, and the search for high-frequency categories for traffic generation.

Globally, there are 4,000 companies that offer food and grocery delivery. In the first half of 2021, more than 170 companies in this category raised financing rounds, surpassing $20B in funding. Out of the $20B, almost $3B was raised between GoPuff, Getir, Wolt, Weee!, and Gorillas. Two leading dark store operators in China, MissFresh and Dingdong Maicai, have both filed with SEC for IPO later this year.

In this memo, we look at unit economics across different business models and determine the key profitability levers in this hyper-competitive and fast-growing sector.

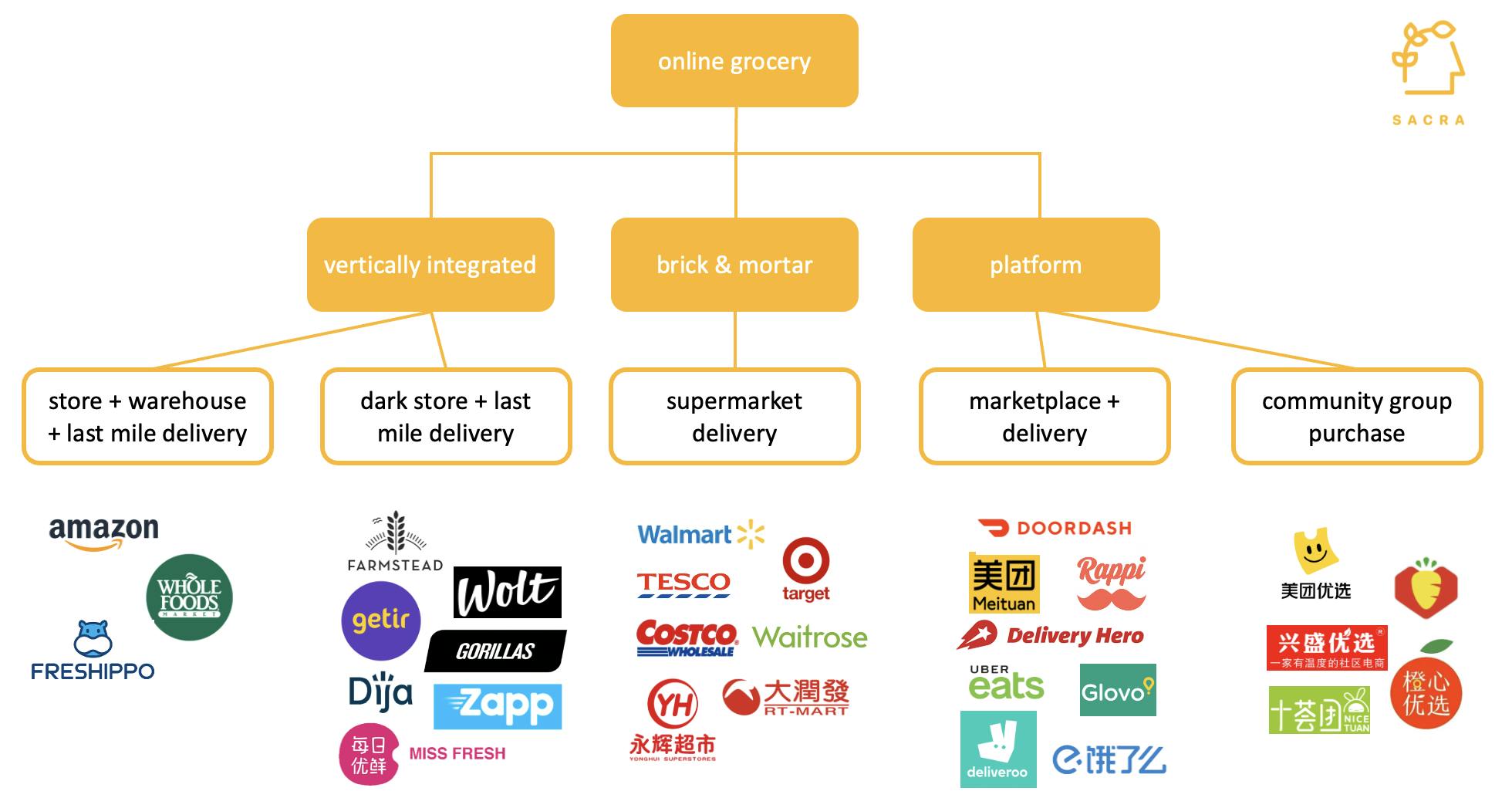

Online grocery falls into two broad categories: platform models and vertically integrated models. Platform models include:

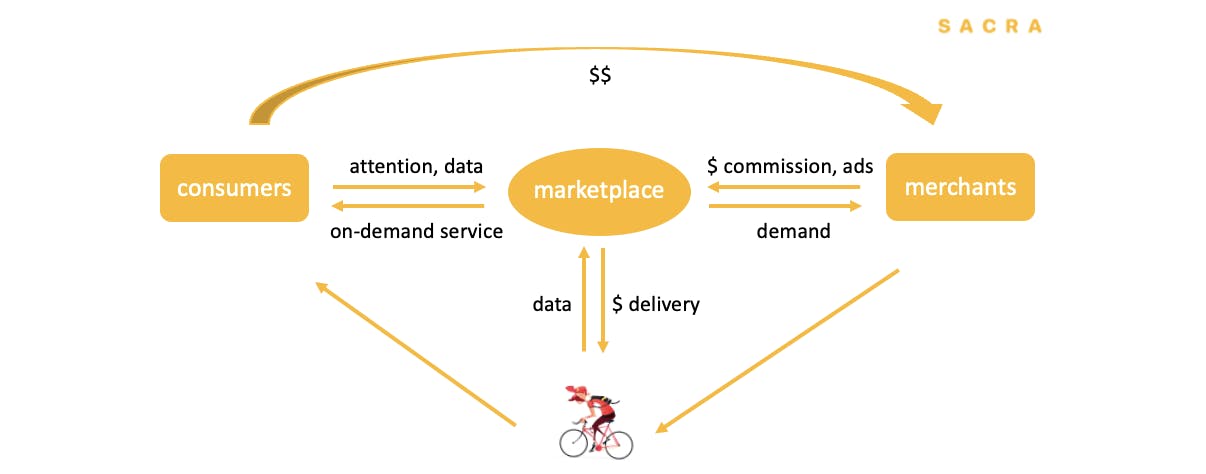

- Third-party marketplaces that connect demand and supply. These platforms also provide last-mile delivery but hold no inventory on its balance sheet. Market leaders include Doordash and Uber Eats in the US, Meituan in China and Rappi in LatAm.

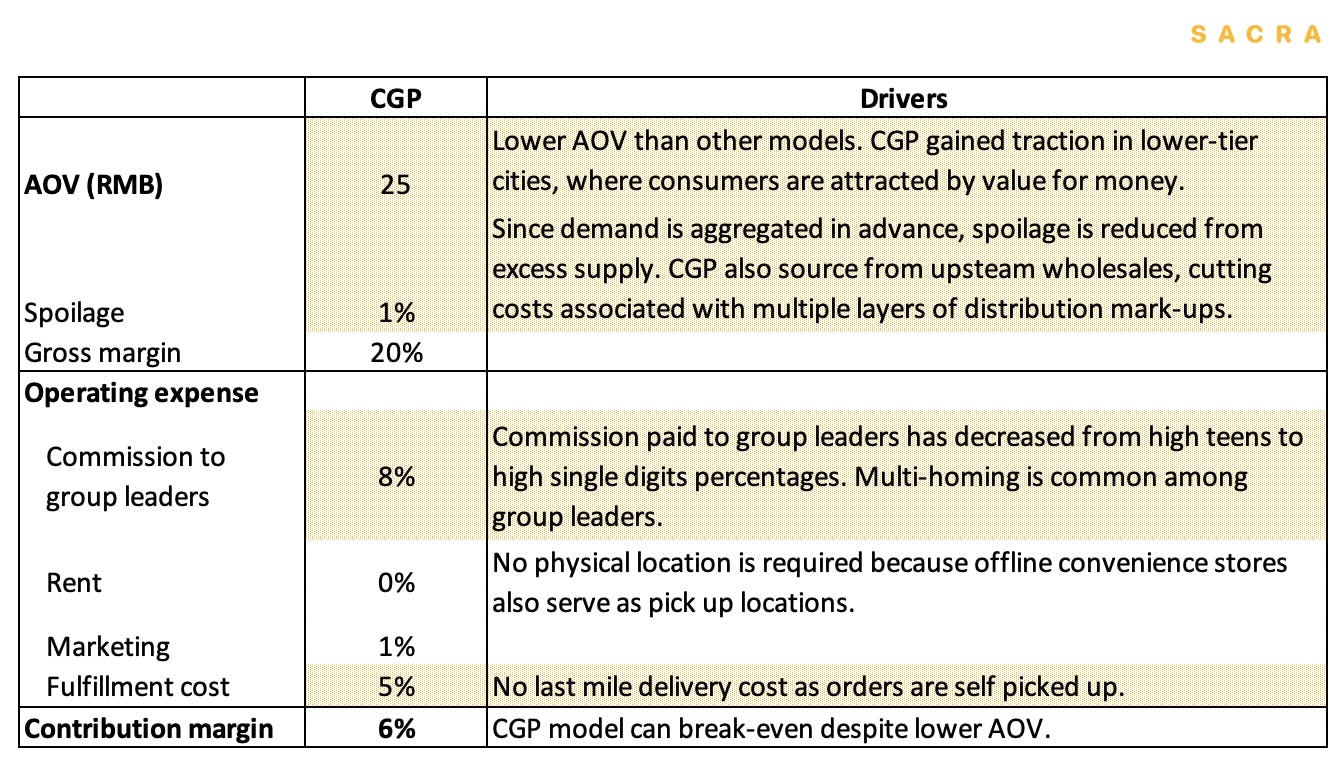

- Community group purchase (“CGP”) is an emerging business model which has gained popularity in China. CGP pays the community group leaders an 8 - 10% commission for their effort to promote products within WeChat groups. Effectively, this arrangement tilts CAC more into a variable cost. Also, CGP is able to eliminate some distributor markups and crowdsources last-mile delivery.

Vertically integrated models include:

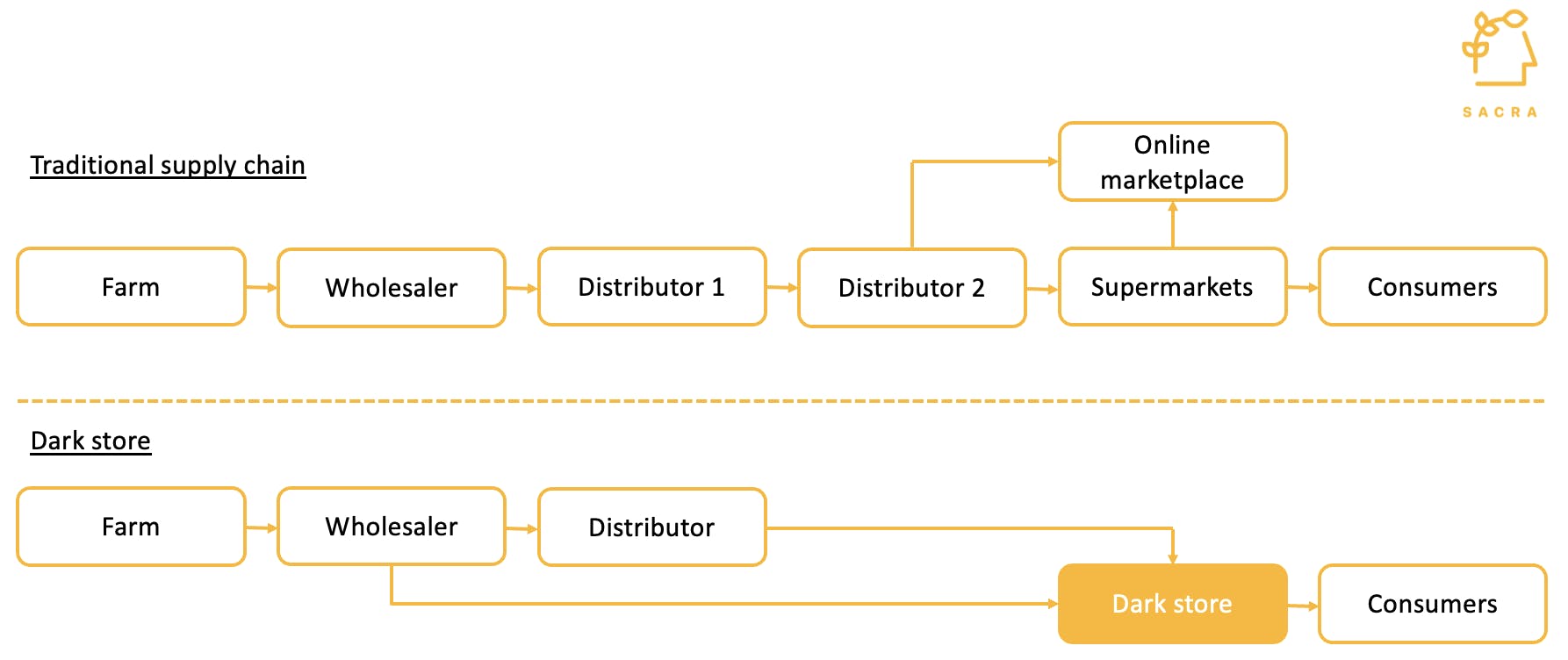

- Omnichannel delivery and dark stores, where companies can move further upstream, procure supply, rent warehouses and manage inventory, as well as fulfill last-mile delivery. This mode of operation is more capital intensive than platform models. However, by being more vertically integrated, companies can have more room for cost optimization.

- Supermarket delivery also falls into this category. However, the cost structure is constrained by existing logistics chains and higher labor costs.

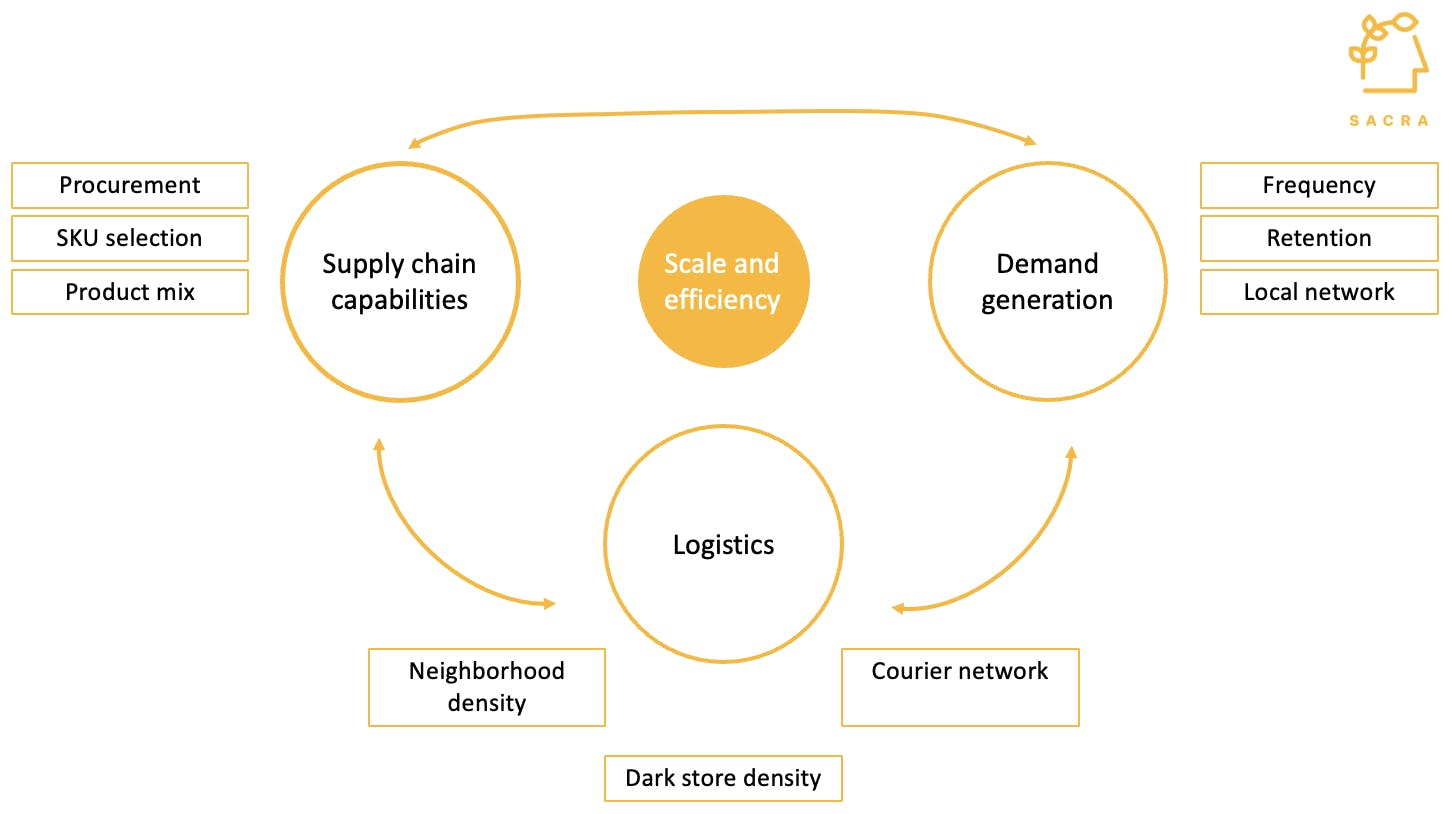

The early-stage online grocery businesses are mostly loss-making due to high capex and low leverage on fixed costs. We believe the core of a successful online grocery business is scale and efficiency. The north star is cost optimization through supply chain management and demand generation:

- Supply chain management: Using direct procurement to cut distribution costs and improve gross margin

- Demand generation: Optimizing product mix to generate demand and gain scale; have the capability to increase basket size through SKU selection and cross-sell, thereby, reducing delivery cost per order

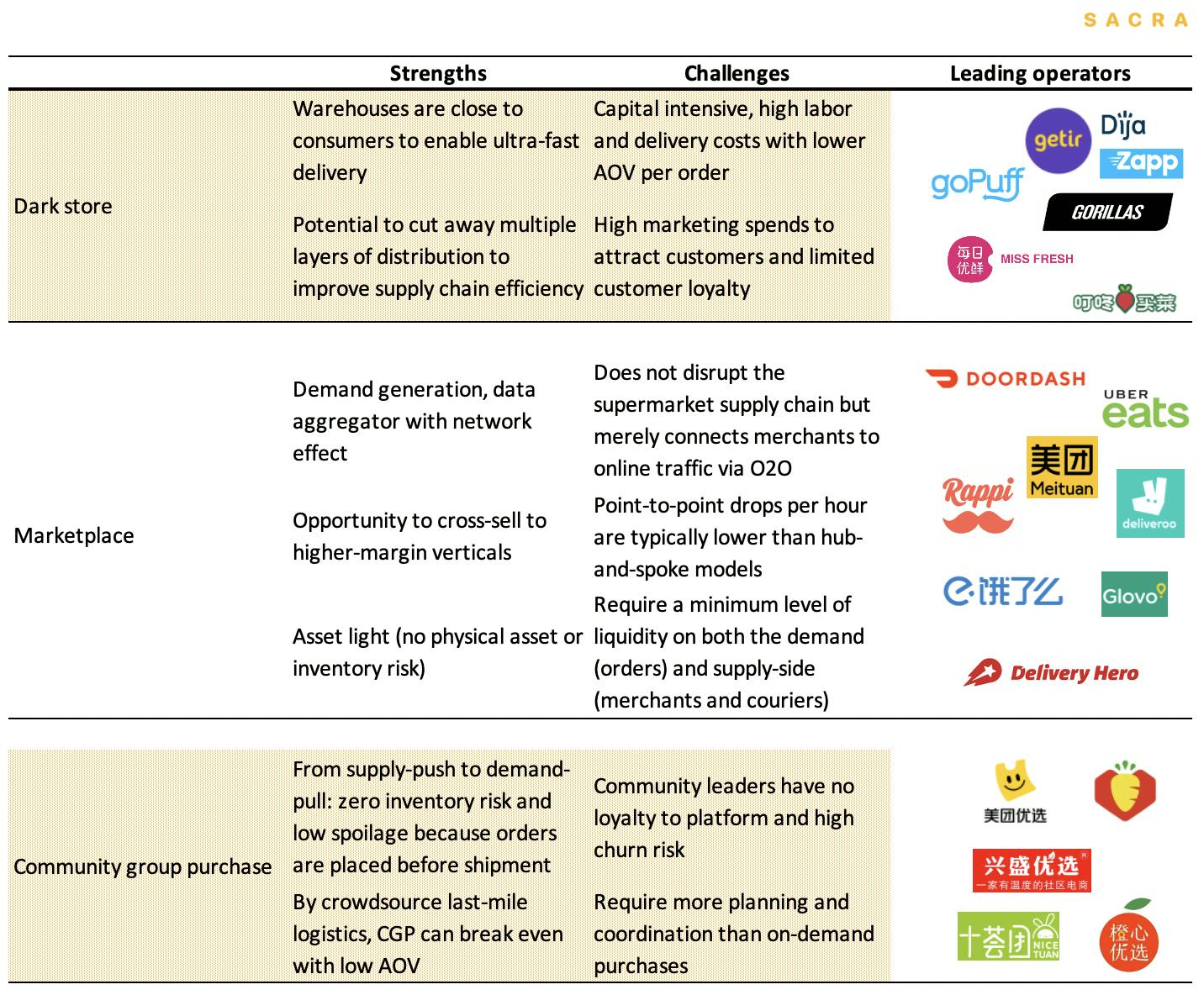

Business models determine the cost structure and have a direct impact on profitability. We summarize the strengths and challenges of each business model below.

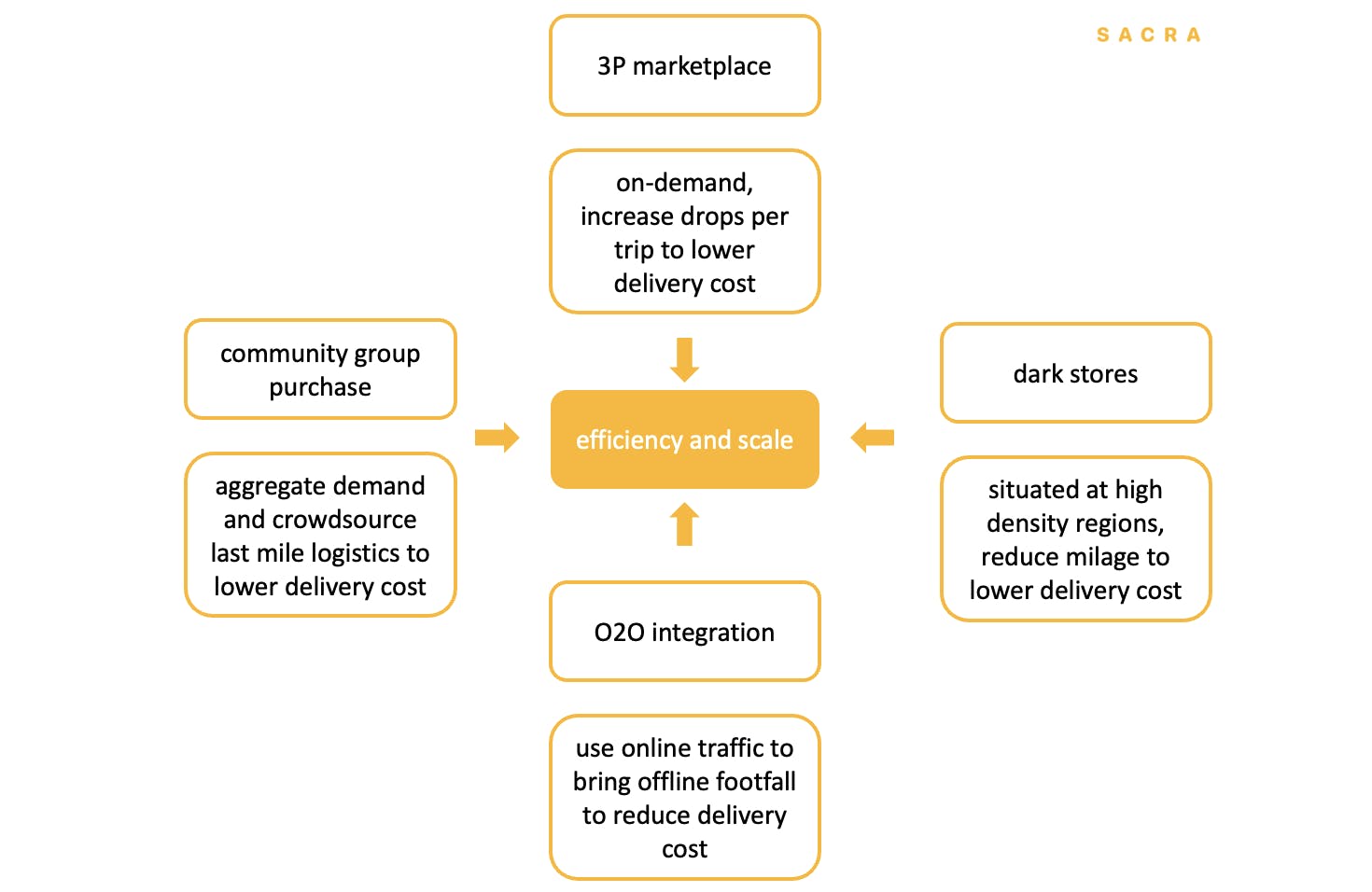

Efficiency improvement and scale are key to optimize cost structure. Operators aim to lower delivery costs through various business models.

Dark stores

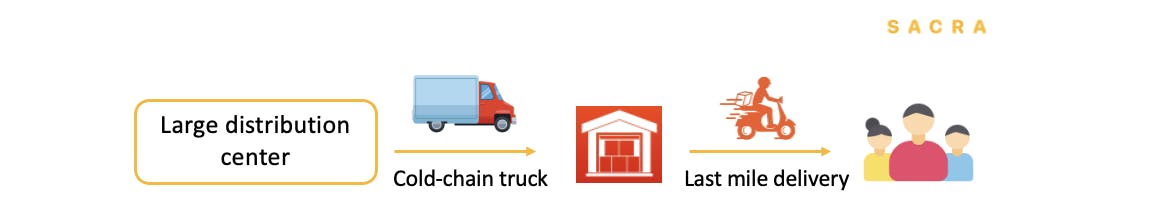

Dark stores operate warehouses in dense neighborhoods and are close to consumers to enable fast delivery.

Getir claims they can complete 6 drops per hour. This is higher than our estimation of 2x/hr for Deliveroo (point to point model), 4x/hr for Domino’s (hub and spoke model) and 5x/hr for Farmstead (pre-order).

To optimize the cost structure, dark store operators potentially cut away multiple layers of distribution through direct procurement. This would increase supply chain efficiency and improve gross margin because every layer of distribution charges a ~20% mark-up.

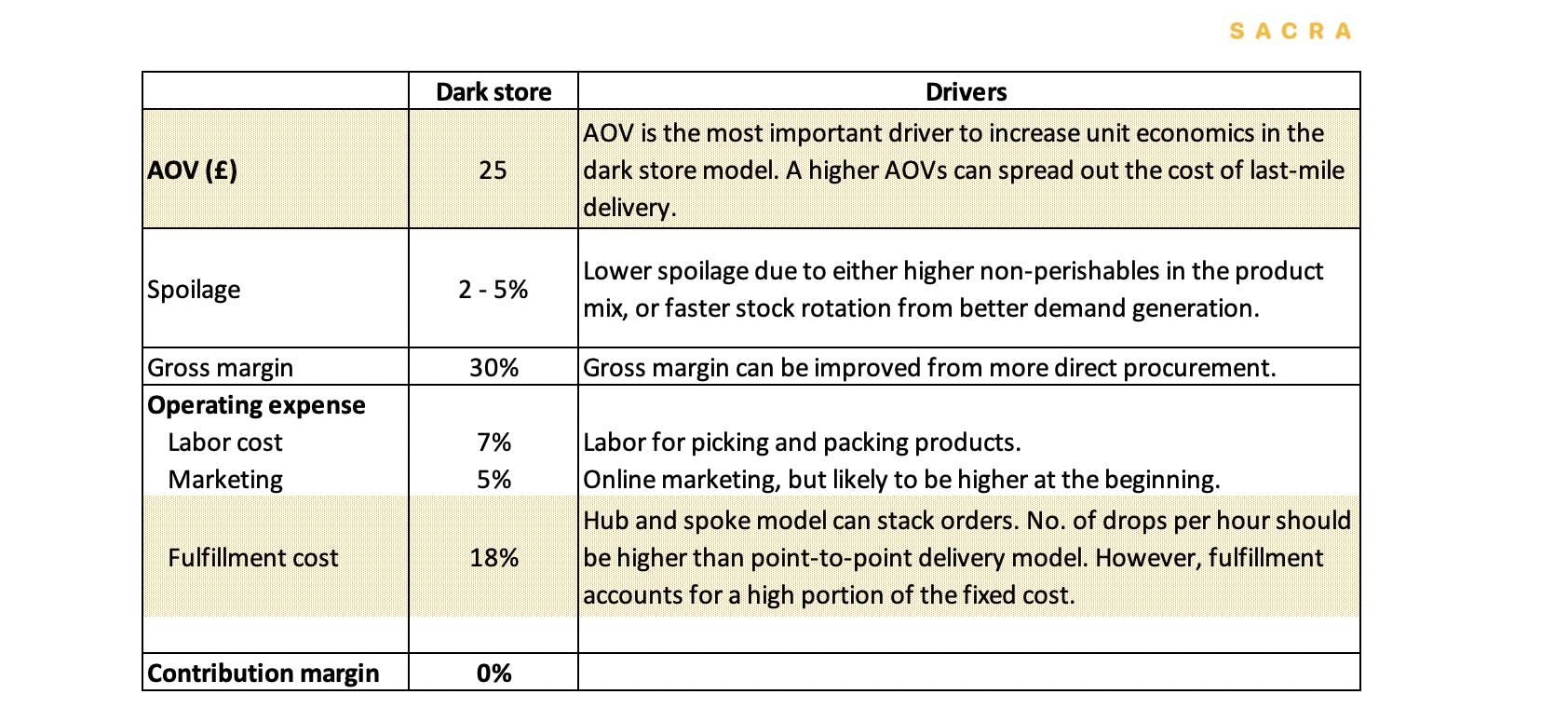

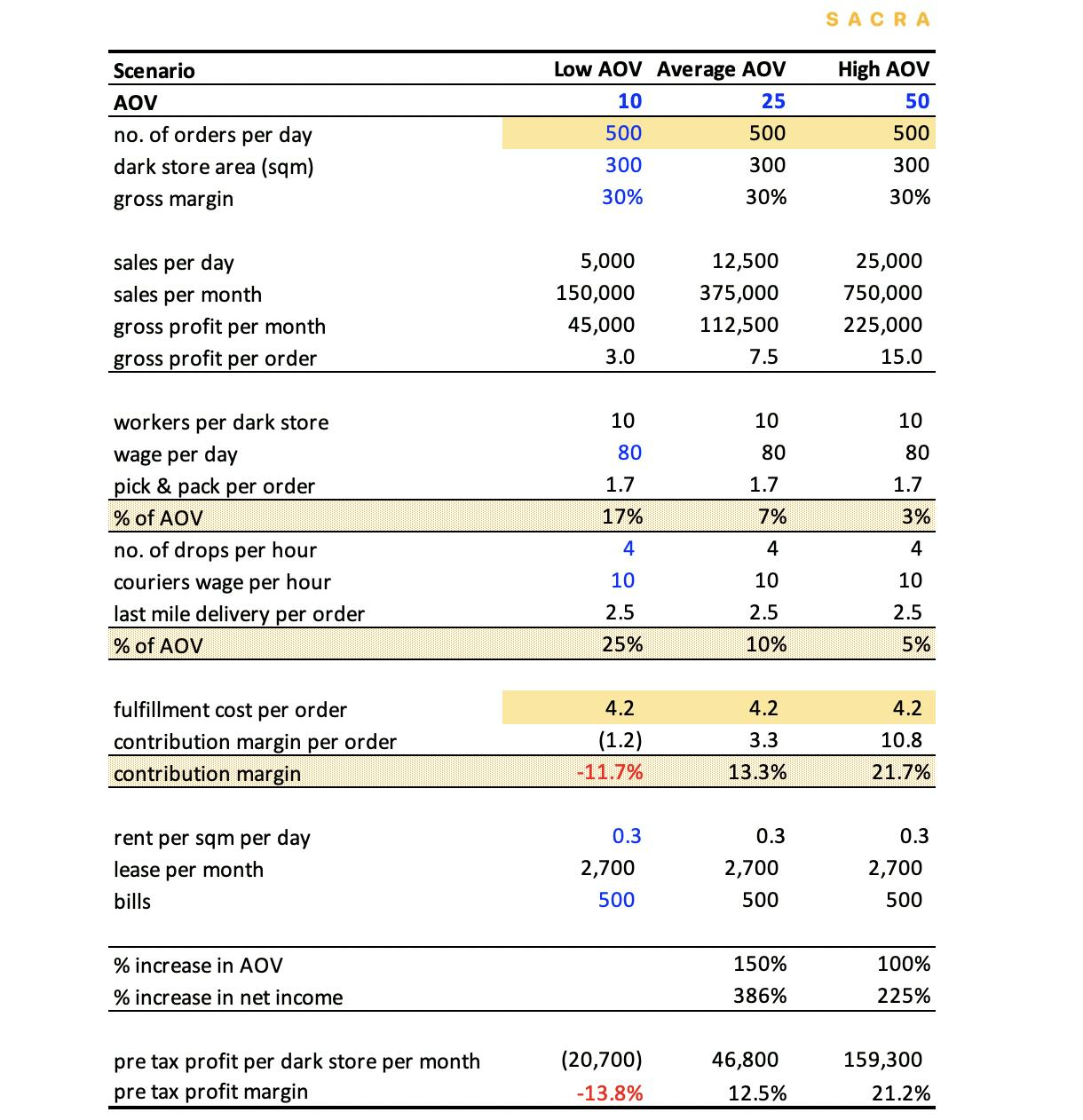

Our primary research shows that the most effective and direct way for dark stores to achieve profitability is to increase average order value (“AOV”). This is because a higher order volume does not reduce labor or delivery costs, which are more or less fixed on a per order basis. When AOV increases, gross profit is higher to cover operating expense, leaving a disproportional benefit to contribution margin.

We illustrate this with an order economics analysis below. Keeping all other variables unchanged, when AOV increases from £10 to £25 and £50, labor and delivery costs as a percentage of AOV reduces from ~40% to 8-17%. As a result, the contribution margin increases from -12% to 13-22%. The pre-tax profit per store also increases from -£20.7K per month to £50-160K per month.

The most effective and direct way to achieve profitability is to increase the average basket size.

Since most of the labor and delivery costs cannot be reduced with a higher order volume, e.g. pick & pack cost is constant at £1.7 per order, a higher order volume without any increase in AOV would risk the business making losses at a faster pace.

Online Grocery Unit Economics, Sensitivity Analysis and TAM

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

Online Grocery Unit Economics, Sensitivity Analysis and TAM

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

Marketplaces with on-demand delivery

Marketplaces connect merchants to online traffic. To ensure a better user experience, many marketplaces offer on-demand delivery services.

Due to strong network effects and effective field sales teams to secure supply, marketplaces tend to stabilize into a duopoly market structure and can become strong demand generation engines.

The weakness of the marketplace model is that it is not vertically integrated and therefore has fewer opportunities to work directly with suppliers. We see marketplace players expand into other business models, such as Meituan, Rappi and Deliveroo running dark kitchens, as well as, Doordash forming partnerships with Farmstead.

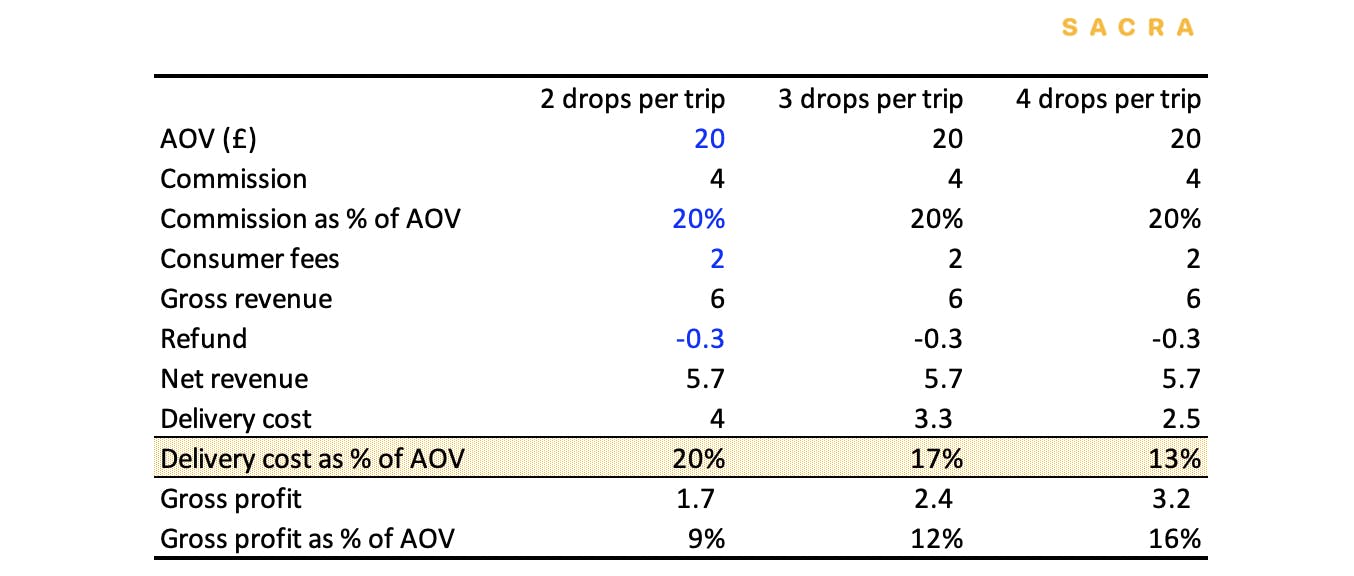

The most important unit economics driver for marketplaces is the number of drops per trip. A higher number of drops per trip can spread out the delivery cost per order. This efficiency improvement is typically a result of better recommendation and route optimization. Marketplaces would then lower how much they pay to the couriers on a per-trip basis. Couriers would earn more on an hourly basis, but the lion’s share of the additional gain would accrue to the marketplaces.

Community group purchasing

Community group purchasing (“CGP”) is the fastest-growing model in China since the COVID pandemic. Consumers in the same neighborhood would order groceries via WeChat mini-programs for next-day delivery to local group leaders or to designated self-pickup points.

Orders are aggregated in the neighborhood by a group leader via WeChat group chats or mini-programs. Consumers self-pickup orders the next day at designated locations.

Internet giants such as Meituan, Pinduoduo and Didi are expanding aggressively into this space. Private players include Xingsheng Youxuan, backed by Tencent and Shihuituan, backed by Alibaba.

We think a structural advantage of the community group purchase model is that it crowdsources last-mile logistics, therefore, significantly lowers the delivery cost per order. In addition, by paying the group leader an 8-10% commission, CAC becomes more of a variable cost, making the model less capital intensive.