David Peterson, early Airtable employee, on the future of product-led growth

Jan-Erik Asplund

Jan-Erik Asplund

Background

We talk to angel investor David Peterson about how product-led growth is changing, with the rise of the hybrid self-serve/enterprise GTM and the increasing importance of customer success.

Questions

- How do you define product-led growth?

- Can you break down what some of those challenges were?

- I'd love to dig into what is this new wave of companies and maybe hear some of these ways that you've seen companies tackling these challenges.

- How do you think about the value of getting that bottom up, having that easy self-serve experience maybe differently than you might have looking at Dropbox in 2015?

- Considering the increase in spend on sales and customer success, how do you think about reducing CAC and increasing revenue per user in this kind of GTM?

- Is there a learning in this new way of PLG companies that land and expand is just not that simple?

- How do you think about pricing with these kinds of SaaS products?

- How does a company with an underdetermined product like Airtable where the key use case is not always so clear think about competition?

Interview

How do you define product-led growth?

I think kind of the simplest way to think about it is companies that have implemented some consumer-inspired product or marketing approaches.

And what that probably looks like is, on the product side, lowering the barrier to entry into the product, making the product dead simple, making it really easy to get started. And linear, right? You know exactly what you need to do to get value out of the product.

On the marketing side, there's lots of different ways... you can think of early Dropbox, right? Referral loops and those types of growth hacks that you heard about in the late aughts, early 2010s, those kind of define this early era of product-led growth.

So what's interesting about that, and what was so revolutionary, is that it meant that really small teams could grow incredibly fast. Because you could achieve this bottoms-up adoption, where end-users were adopting the product.

You no longer needed to sell it, top-down. End-users were adopting, and they were inviting others. And that let you expand incredibly fast without ever hiring a sales team, right? Without ever having anybody customer-facing at all.

The product itself was doing the selling because the product was so simple, so easy to use, and through all these referral growth loops, whatever else. And then once you built some upgrade loops into the product as well, now you're starting to get revenue again without actually hiring a sales team.

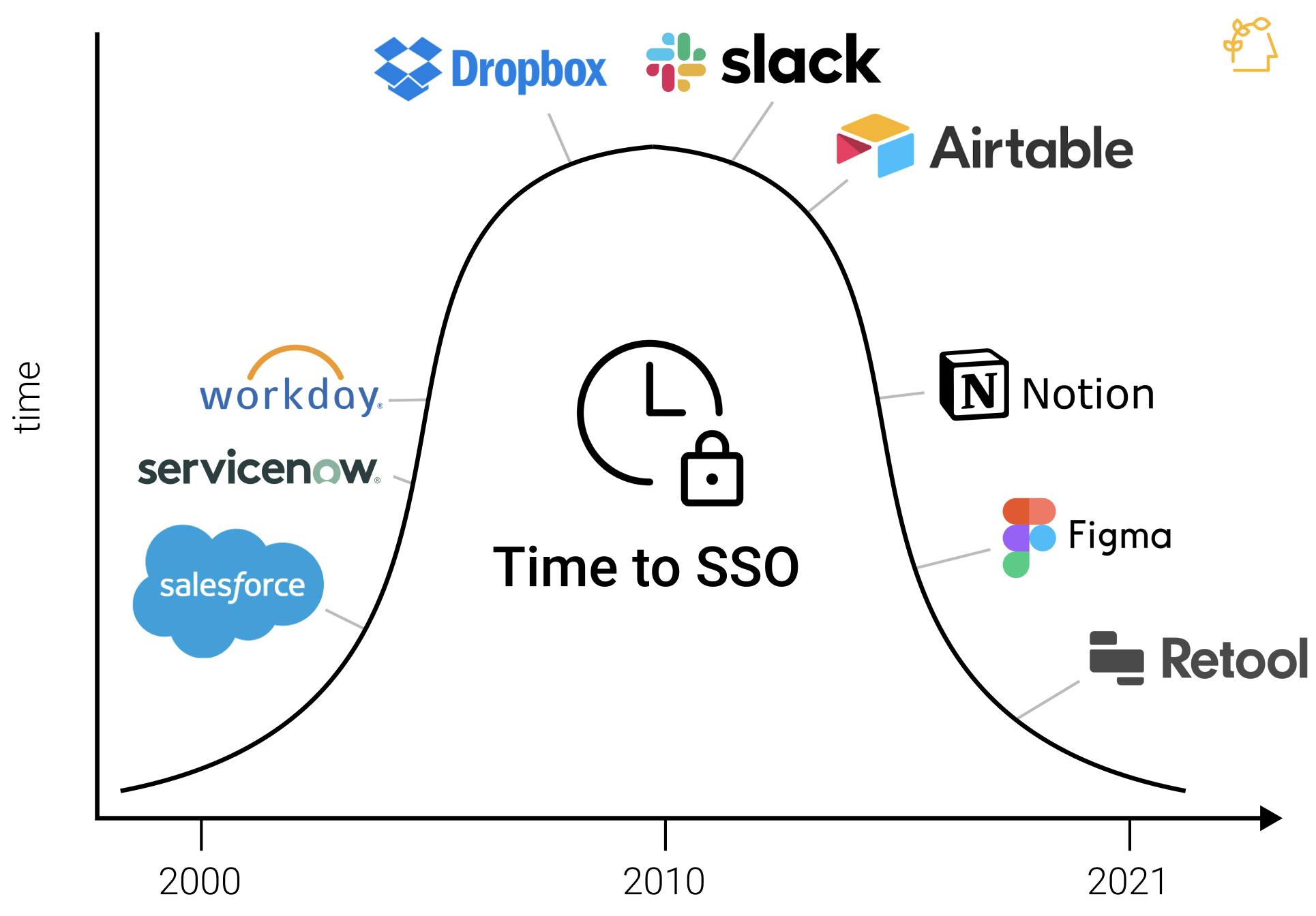

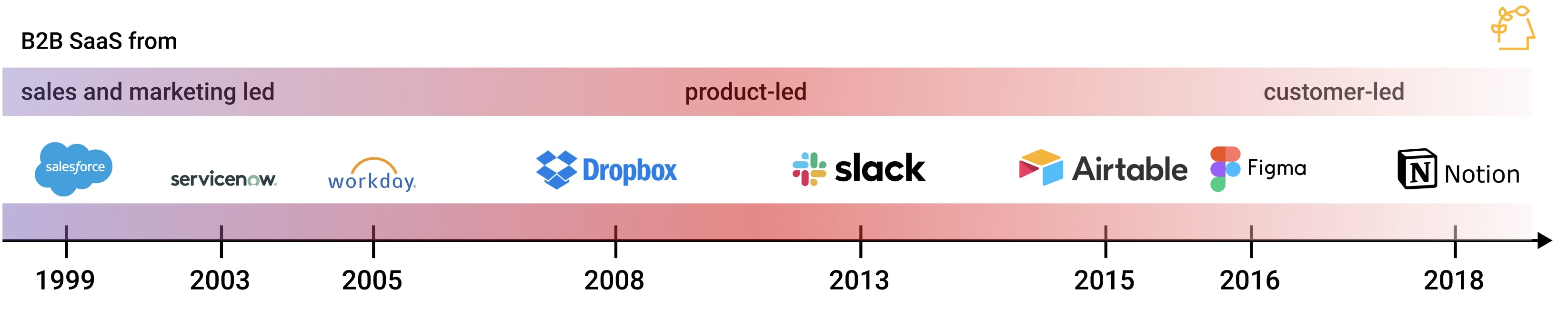

So I think of that as being this first era of product-led growth, really typified by companies like Dropbox and Slack, let's say, in, again, the late aughts, early 2010s, early teens. And they were successful in proving this model. And it truly was a sea change in the way that companies, B2B companies in particular, could go to market.

What I find interesting about it is I think a lot of people, when they talk about product-led growth today, they think that that is still what product-led growth is and should mean. But it feels like we're actually shifting.

We're evolving into a new era because there are these really fundamental challenges with that first era of product led growth.

And I feel lucky that I was at Airtable during this time because I think Airtable kind of straddled these two eras.

Airtable's founded in 2012. So at that point in time, what were the companies you looked to for inspiration? Dropbox was a huge one back then. Dropbox was the company that had figured this out.

But Airtable's first product wasn't launched until 2015. First revenue in 2017, right?

By that point we had started this evolution. We had entered this next era, and I think Airtable ended up kind of straddling both. And we, through a lot of the challenges we faced with this first era of product-led growth, also had tried to figure out, "What does the second era look like?"

Can you break down what some of those challenges were?

Yeah. I think for both Dropbox and Slack, at a high level, the challenge they had was all about moving up market, and shifting from being a really end-user/consumer-driven, bottoms-up adopted product to one that could be adopted at enterprise scale.

I think there's a few shortcomings to the pure product-led growth strategy that might have resulted in that challenge for them.

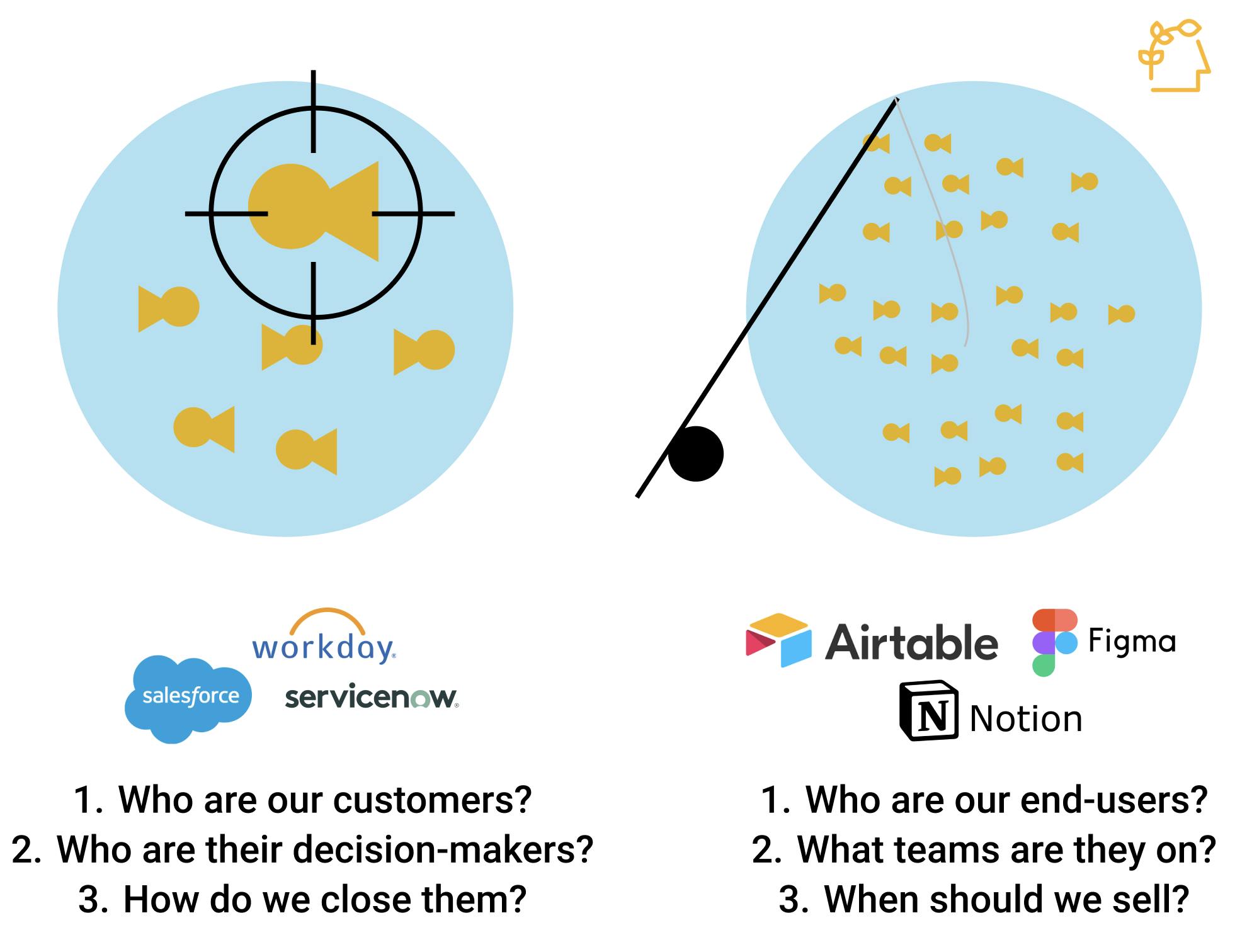

One is that the adopters of your product aren't necessarily the buyers of your product. So we are seeing more and more functional leaders and line managers have budgets to just buy software, right? A lot of people have credit cards today. They can swipe. So it's certainly easier than it used to be, but also, it remains the case that end-user adopters of products aren't necessarily the ones who can buy.

There's also a complex success/sales process you need to go through now to compile all of the end-users and turn that into a sales strategy, like:

Who are all of the end-users we have?

What teams are they on?

Is now the right moment to try to turn this into a sale, or should we just let people continue to use the product?

That is now a decision that the sales team needs to make. That's a way different motion than just reaching out to the buyer and pitching them and trying to drive them through a funnel, right?

And I think that kind of leads to what I think of the second shortcoming, which is layering on sales after the company has scaled up, and there's a ton of users, and you're growing really fast.

Tons of operational complexity there, and I see two parts of that. One is what I was just referring to, which is if you already have a lot of users, then the sales process is just going to be way different. Different metrics matter. It's a whole different system.

Something we talked about sometimes at Airtable, and I've been thinking about this a lot, is it's almost like fishing a pond. And you are stocking that pond with every new user, and you're letting those users swim around and grow.

There's a moment when you should go fish, and you want to go try to sell to them, and help them get even more value, help them upgrade. But you don't want to fish too quickly, because you need the pond to remain healthy.

So then there’s a whole other set of metrics that you might think about from a systems design point of view:

What is the input rate of new leads?

What is the activation rate, evolution rate, where a lead becomes warm enough that it's worth reaching out to?

What's the replenishment rate of the system?

Those are things you want to care about. Those are not normal sales metrics. That's not the normal way for a sales team to run itself. And so that's a hard transition.

There's also this operational complexity just around where the centers of power are within an org, right? If you've grown to hundreds of thousands, millions of users on the back of product and maybe some marketing, then all of a sudden sales comes in, you're setting the stage for a political battle, whether you like it or not.

A long time ago, this was all sales lead, and then it was sales plus marketing, and now it's just sales and marketing and product, right? We just need to be working even better together, but I think that's a transition that people are somewhat uncomfortable with.

The last shortcoming, which definitely I think is typified by Dropbox and Slack but other companies as well, is that the kind of bottoms-up, simple, viral product design that won them all of those initial users, that design is undermined by enterprise customer needs.

All the enterprise features that you need to build undermine the simplicity that won you the bottoms-up growth to begin with, so that the bottoms-up channel ends up getting somewhat ruined. But if you haven't figured out the top-down channel yet because your sales team is dealing with all this complexity, then all of a sudden you're in a lurch.

I think those are three big shortcomings with the pure product-led growth approach. And I think we saw some of those at Airtable.

I've also definitely seen these at peer companies, like other folks that we worked with, and I think that there's a better way that companies are figuring out.

I'd love to dig into what is this new wave of companies and maybe hear some of these ways that you've seen companies tackling these challenges.

Yeah. I think there's a few differences. One is that products of the classic product-led growth era were incredibly simple. Right? Designed for quick adoption. They were consumer inspired in their simplicity.

I think we're seeing that change. The products... Airtable is a good example of this, but I would also point to products like Figma, or Retool, or Webflow. Right? Nobody would describe these products as simple. These are deep, complex, incredibly valuable products.

And the way I like to think about it is, these products have a low barrier to entry, but they also have an incredibly high ceiling. So, you can get value out of the product really quickly if you want. You can get to an aha moment relatively quickly, but you can keep building for the next year and never hit the ceiling, keep on getting additional value.

So, I think that is something unique and different from kind of the first era of product led growth companies.

I would call out, by the way, that's an incredibly hard product challenge to build a product like that. So, it's worth noting that that requires incredible product leadership to be able to boil down that much complexity, but still keep it intuitive.

Because look, you can look at the last generation of enterprise B2B companies, those products were also complex. They were complex. They were also just incredibly hard to use. Nobody liked using them. But, because you were selling top down, it didn't really matter. As long as they solved the problem that the buyer cared about, they would get bought.

Now, we're trying to combine both of what came before, simple bottoms up adoptable products with the same complex superpowers that previous enterprise companies had.

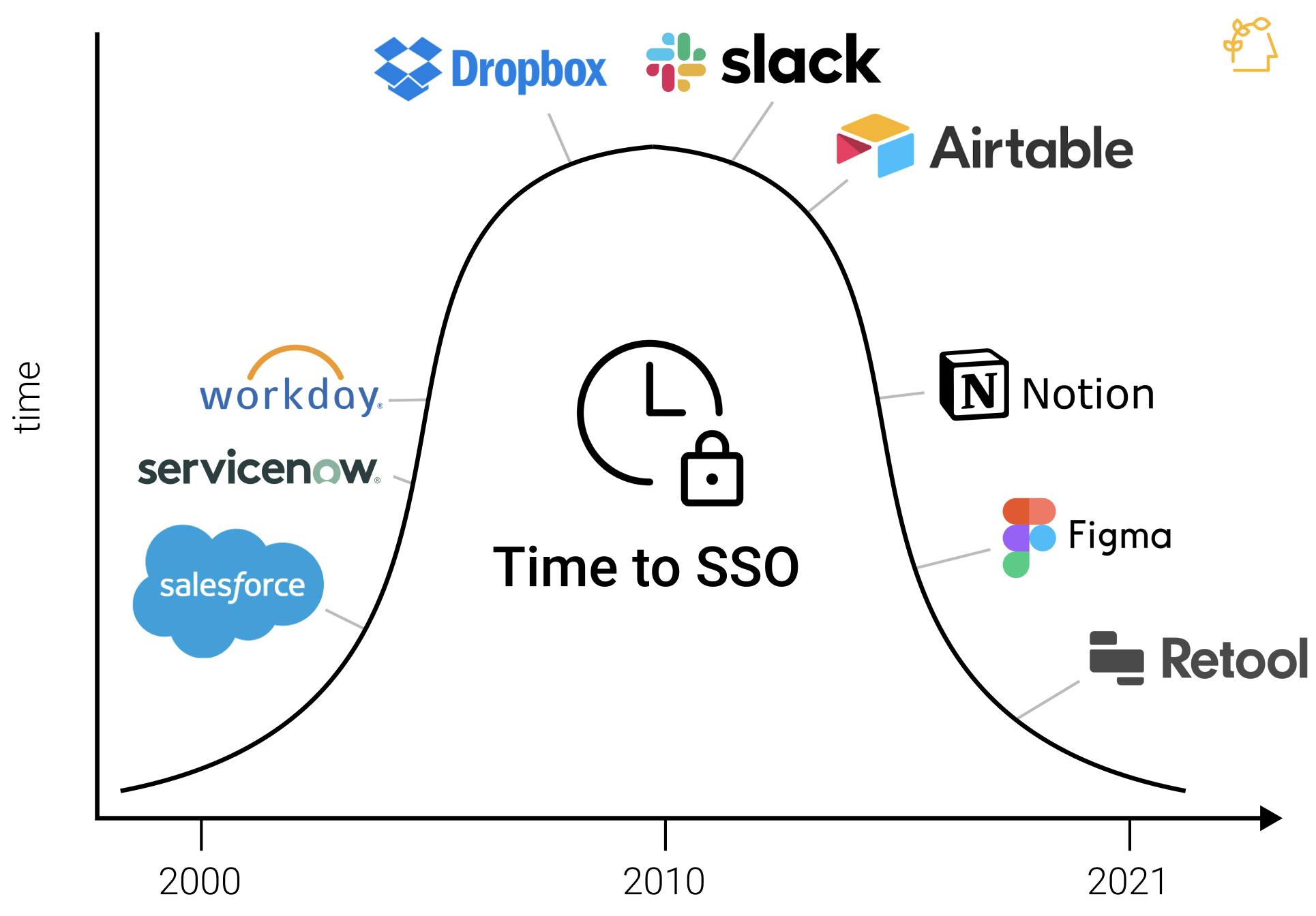

That's a step function change in complexity, I think, from a product point of view. But that's what we're seeing with companies now. I think, related to that, something we're seeing is more and more companies are coming to market with enterprise ready... they're enterprise ready from almost day one.

Airtable is not an example of this. Right? Like we launched a product that, back when we launched it in 2015, I joined a little bit later, but back then, right, Airtable did not have kind of the classic enterprise features. But I think we're really seeing like a decrease in the time-to-SSO. Right? Now, new SaaS products are launching with SSO, with enterprise admin like on day one. So, it's just another example of how the complexity of products is increasing, even though they're still going bottoms up.

And this is an interesting trend because you can see it both in companies building this way and in companies that are helping companies build this way.

So like, look at WorkOS or Vanta. These are companies that are helping others launch with SSO or launch with SOC2 right from the very beginning. Whereas previously that was a Rubicon you needed to pass.

After you hit a few hundred thousand users, all of a sudden you needed to take six to nine months to get SOC2. And it was a huge annoyance that would distract half the team for that whole time.

Now, people are just launching with that stuff on day one. Right? That is like a fundamentally different approach to go to market.

A few other differences that I've noticed, one is I think a lot of people are taking inspiration from Superhuman and just creating onboarding teams that are focused on high touch onboarding.

Superhuman, I think they were innovative in this regard. And a lot of other teams are taking that and running with it.

I think you'll also see a lot more education. Because these products are so much more complex, right, there's such a large upside to making sure that you can scalably educate your big pot of users and make sure that they are getting as much value as possible.

Especially because, going back to that fishing pond analogy, right, like your goal in many ways is to get new fish into the pond and then fatten them up, like activate them, get them to extract value from the product so that your sales team can go fishing.

What I've seen is a lot of teams now, you can kind of split the customer facing org too. There's a bunch of teams that are focused on activating new leads, making sure they're getting as much value as possible out of the product.

There's a bunch of people who are focused on, once a user is ready to go, whether they've raised their hand or not, whether they've said, "I want to talk to a salesperson," or not, once they're at the point where you think they're likely to want to talk to sales, they're likely to want to upgrade, then you very deftly go and start to have a conversation with them about it.

How do you think about the value of getting that bottom up, having that easy self-serve experience maybe differently than you might have looking at Dropbox in 2015?

Yeah. Well look, I think the utility of it is, if people can bottoms up adopt your product, that means you can decouple growth, user growth from employee growth.

If you are purely a direct sales led organization, then your revenue is going to be a function of the number of sales reps you have at the company. That's it.

With bottoms up, with a product that's kind of tuned for bottoms up growth, that is no longer the case. You can get hundreds of thousands, millions of users with a really small team. So, that is a superpower.

The other thing I'll note is it also increases the addressable market massively. If you have a direct sales organization and that's the only way you can go to market, then there's a whole bunch of companies that it would never make sense for you to talk to.

The average revenue is just going to be too low. The ROI is not there for you to talk to them.

But with bottoms up and self-serve adoption, now anybody in the world can be your customer. Any knowledge worker anywhere in the world can be a user, and any of them can be a customer if they can swipe their credit card. So the big difference is this long tail and the fact that the growth of that long tail is decoupled entirely from the investment that you as a company need to make in staff.

Considering the increase in spend on sales and customer success, how do you think about reducing CAC and increasing revenue per user in this kind of GTM?

Yeah. Yeah. So, two thoughts come to mind.

One is, with products like the ones we're talking about, which may be bottoms up adopted, but are much more complex and provide candidly way, way more value to the end user, I think basically everybody can be charging more. Like you shouldn't be anchored to the price of Dropbox or Slack You should be charging way more than products like that.

Which I think you see, right, in a lot of these products. Like this new era of bottoms up adopted products, they're no longer $5 per user or $4 per user. Like people are charging $20, $30, $40, $50 per user. So, that is a different universe, from a price point of view, which helps you with your cost of acquisition.

Another thing to think about with a lot of these products is how widely they can be adopted within an organization, and how that can influence how you think about the cost of acquiring an initial user.

This is a little bit more relevant to a company like Airtable, which is this purely horizontal product than a product that is a little bit more vertically focused, or functionally focused.

But with Airtable, we would think a lot about, what is the land use case, or hook use case where we can get into an organization? And then, what are the natural ways that we might expand over time?

And what that lets you do is it lets you think about, well, the flipside of the cost of acquisition of this one team isn't just about the LTV of this team over time, it's all of the natural expansion we expect we'll see, because we've seen this before it at similar organizations as well.

Is there a learning in this new way of PLG companies that land and expand is just not that simple?

Yeah. I think there's some nuance there. So from my experience, I've seen natural expansion within anything from an SMB mid-market to Fortune 50. That happens. Somebody becomes an uber evangelist of a product and just start sharing it around, and then all of a sudden you see a bunch of new people signing up and they're getting excited too. That definitely happens.

So I think land and expand exists, but it's not as simple as any of us hoped it would be.

I think the lesson I would take from Airtable is that the deeper, more complex, more valuable your product is, no matter how intuitive it is, you have to put in the work to make sure that people are capturing that value.

And you might do that via high touch or scaled education, but you need to put in that time. To compare it to a company like Slack or something, there isn't the same kind of value in the network. Right?

The power of these products is that each end user can actually individually get a ton of value out of it.

At Airtable, we always talked about how we were trying to democratize software creation. Anybody should be able to build their own piece of software. But of course, that doesn't mean that it's built for them, that means they need to build it for themselves.

That takes effort. That takes some investment of time and mental bandwidth. And we realized it was incumbent on us to help people along that path.

And I think for a lot of other companies, one way to grease the wheels there is to understand what is the land and expand path.

If you land in this use case, what are the most common next use cases? Or if you land in this team, what's the most common expansion pathway from there?

If you understand that, if you can map it, then you can accelerate it yourself because you can... It turns out a lot of companies, their marketing teams and their design teams work together in somewhat similar ways. So there's some learnings that you can bring across accounts.

How do you think about pricing with these kinds of SaaS products?

I've been talking with a few companies recently that are solidly enterprise SaaS companies, but they're thinking more and more about doing usage based pricing because they have some part of the product that is usage driven.

Which I think it's really interesting because they recognize that seat based pricing has this perverse effect of penalizing people for inviting their teammates and that you don't want to do that, right?

If your goal is expansion, then you want this to be used by as many people as possible, but with a product like Airtable, we just didn't have the lever to charge any other way.There was nothing in the product that let us do that from the early days.

But I've seen a lot of products recently that are thinking about this from earlier on, like what are other angles that we can charge based on and instead giving away teams or user seats essentially for free just to drive more of some other fundamental metric.

How does a company with an underdetermined product like Airtable where the key use case is not always so clear think about competition?

I think that the reality is that because of how horizontal Airtable is as a product, Airtable has both a ton of competitors and no competitors. It just depends on how you want to look at it.

I would think of it as horizontal and vertical. So you can look, there's a few horizontal competitors out there that are also somewhat generic, broad. The best example of that would be just spreadsheets in general. People use spreadsheets to solve countless problems. A lot of those problems are probably better solved with a database, but previously it was just really hard to just spin up a database, so you used a spreadsheet instead.

So Airtable has a lot of work to do on educating the general public, the knowledge worker public, on the value of databases in a way that doesn't scare people, which has always been the challenge.

Then I think that there's a lot of vertical specific or use case specific competitors as well in the project management space. Which in and of itself is pretty broad, but yeah, Airtable very often is competing with Smartsheet, and Asana, and Monday, and all these other classic project management SaaS platforms.

But you could say the same thing, just going down a list of content calendars, or product road mapping, or tools, or bug tracking tools, there's a long, long list of these and there's competitors in each of them.

That being said, what I think is really exciting about Airtable is it's easy to think about the B2B software market as being a bunch of verticals. There's the CRM, there's the ERP, there's the content calendar, social media marketing system, whatever.

And it's easy to think that you're entering that market, that is the market that you're competing with, each of them is a circle that's a pie. You're competing for market share within that pie, and CRM is way bigger than social media marketing whatever.

Realistically, Airtable is going to take a little piece of all of those pies, because you can use Airtable to be an ERP. And I know countless small businesses that are basically just running everything on Airtable now, because it's flexible enough to serve that purpose. And it could be a CRM, it could be any of these things.

I think the real opportunity for a product Airtable is actually all the white space in between all of those markets. What are all of the pieces of software that heretofore went unnamed or unbuilt because people didn't have the tools to do it?

They just hacked something together with spreadsheets and email and a few other things, and they called it a process or a system, but actually it could be software if they had just known how to turn that process that they had designed into something like software with code. But with Airtable, now they can turn that into something.

So I actually think that is the real opportunity. And my guess is the white space in between all the other markets dwarfs the size of those markets themselves. So despite the competition, I think there's a lot of upside there.

Disclaimers

This transcript is for information purposes only and does not constitute advice of any type or trade recommendation and should not form the basis of any investment decision. Sacra accepts no liability for the transcript or for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies in respect of it. The views of the experts expressed in the transcript are those of the experts and they are not endorsed by, nor do they represent the opinion of Sacra. Sacra reserves all copyright, intellectual property rights in the transcript. Any modification, copying, displaying, distributing, transmitting, publishing, licensing, creating derivative works from, or selling any transcript is strictly prohibited.