Fintech Fastlane: The Unit Economics of the Banking-as-a-Service Toll Road

Jan-Erik Asplund

Jan-Erik Asplund

For more research on fintech and the private markets, sign up for our email list here.

Success!

Something went wrong...

Life in the BaaS lane

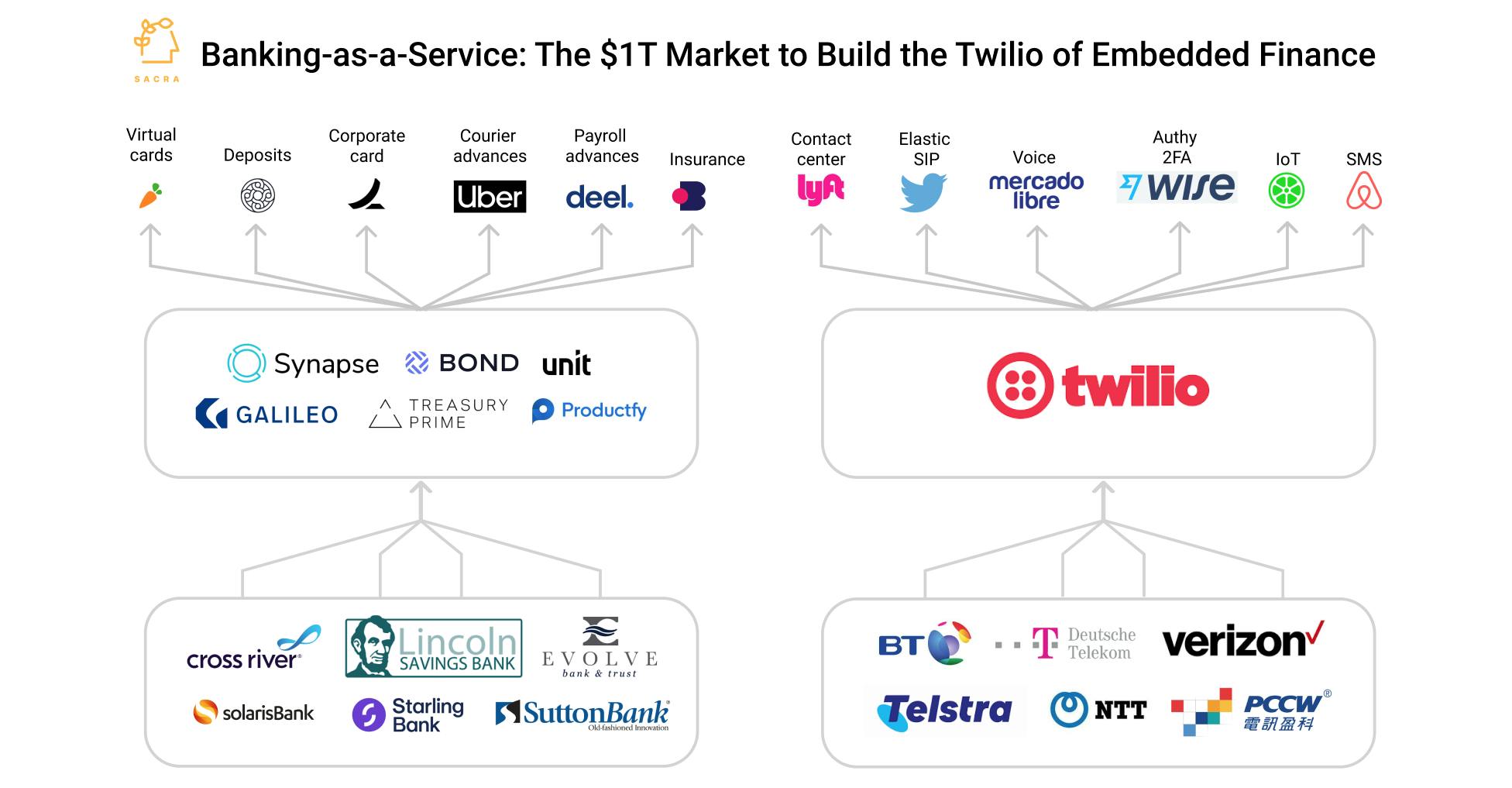

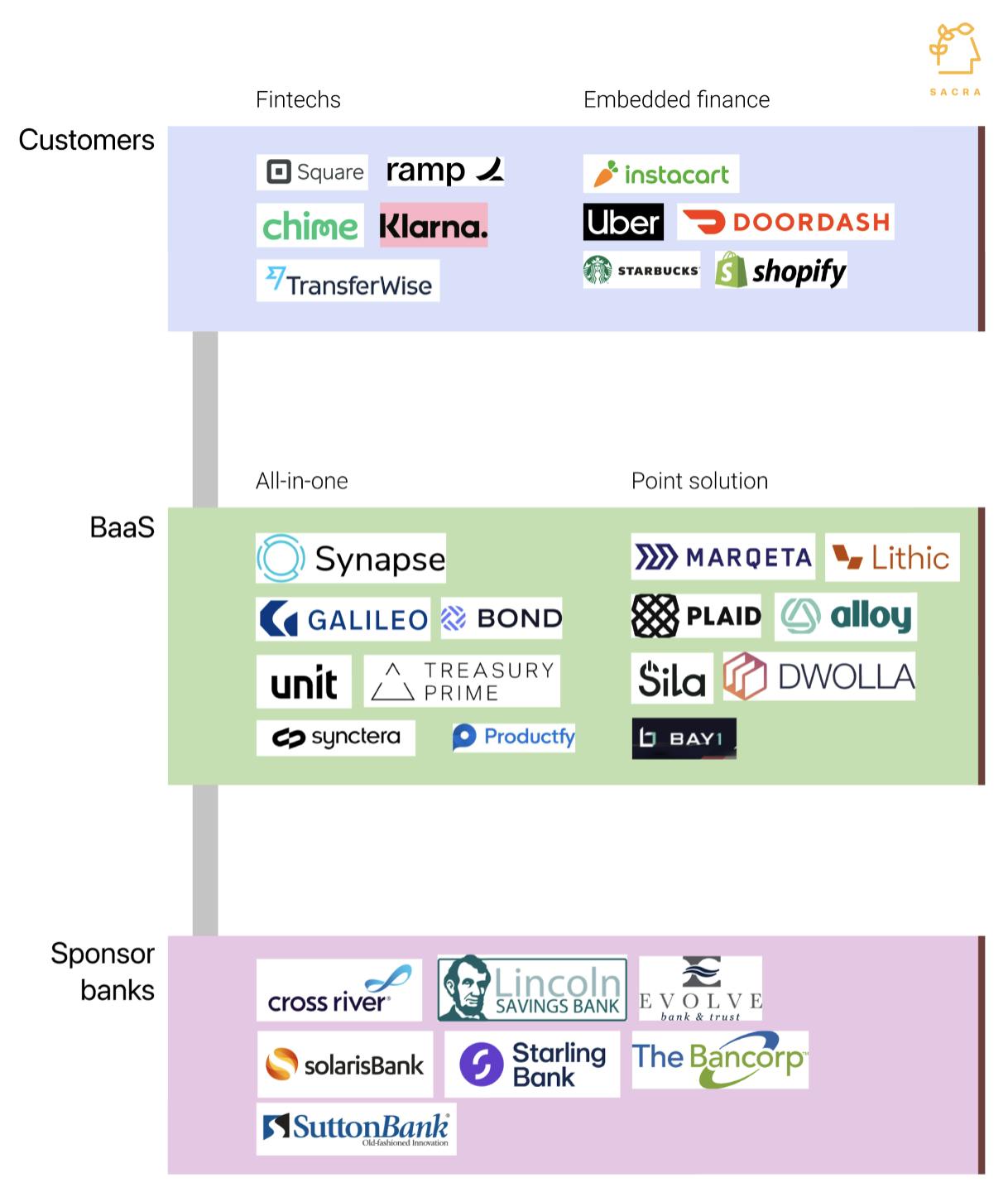

Banking as a service (“BaaS”) companies effectively provide a fastlane for fintech companies and brands with embedded finance functions (e.g. Uber, Doordash, Instacart) to launch financial features like physical or virtual card issuing, payment processing, and authorization and settlement of transactions without directly partnering with a bank.

While working with one of these BaaS providers to launch a card program or open up deposit accounts for users might cost these brands more than doing things the old way, using this "fastlane" allows them to get to market faster and build something more finely customized to their needs.

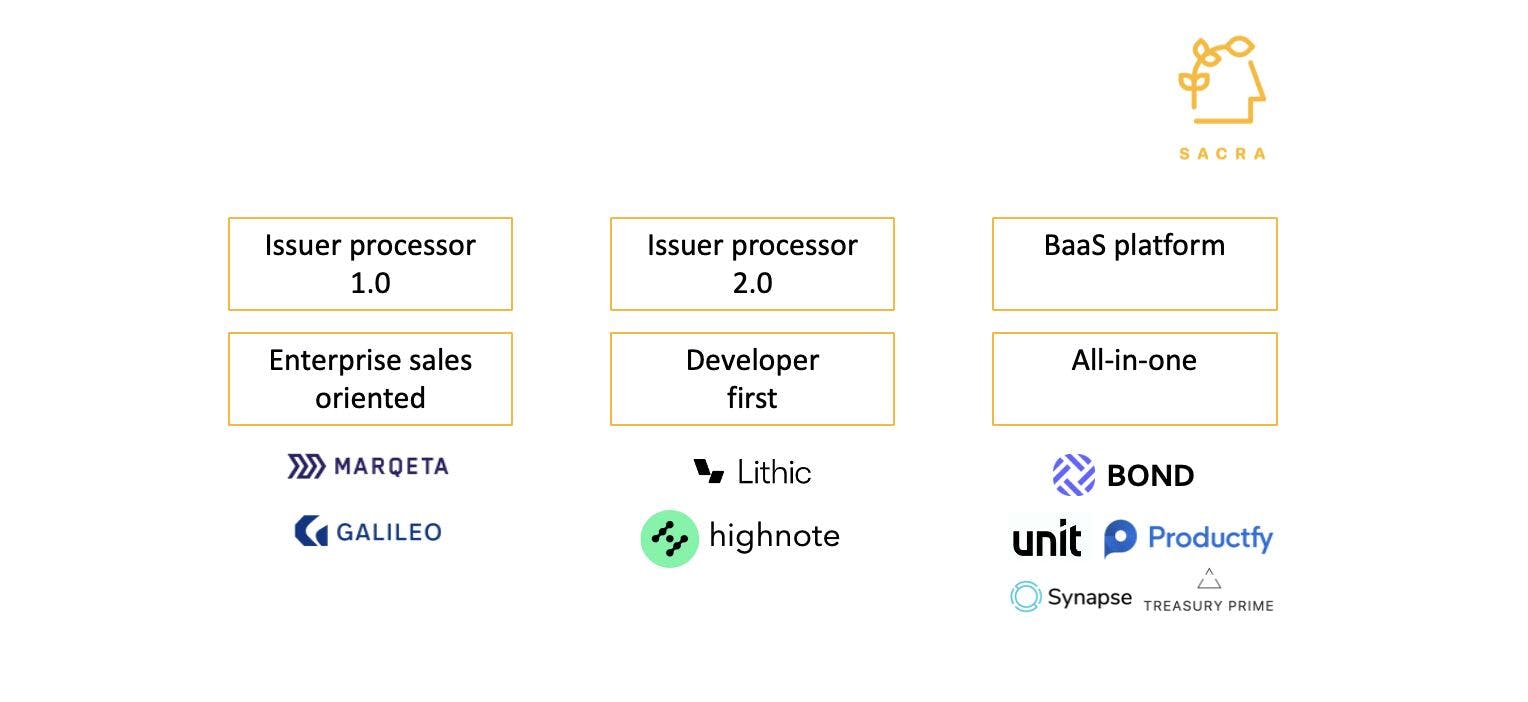

Competing with legacy payment processors like Fiserv, FIS, and TSYS and banks that offer APIs, BaaS companies use the internet to get customers and are developer-first and API-oriented, targeting the implementers of fintech and embedded finance.

In connecting modern companies to the financial infrastructure of banking, fintech companies use banking-as-a-service platforms which rely on sponsor banks.

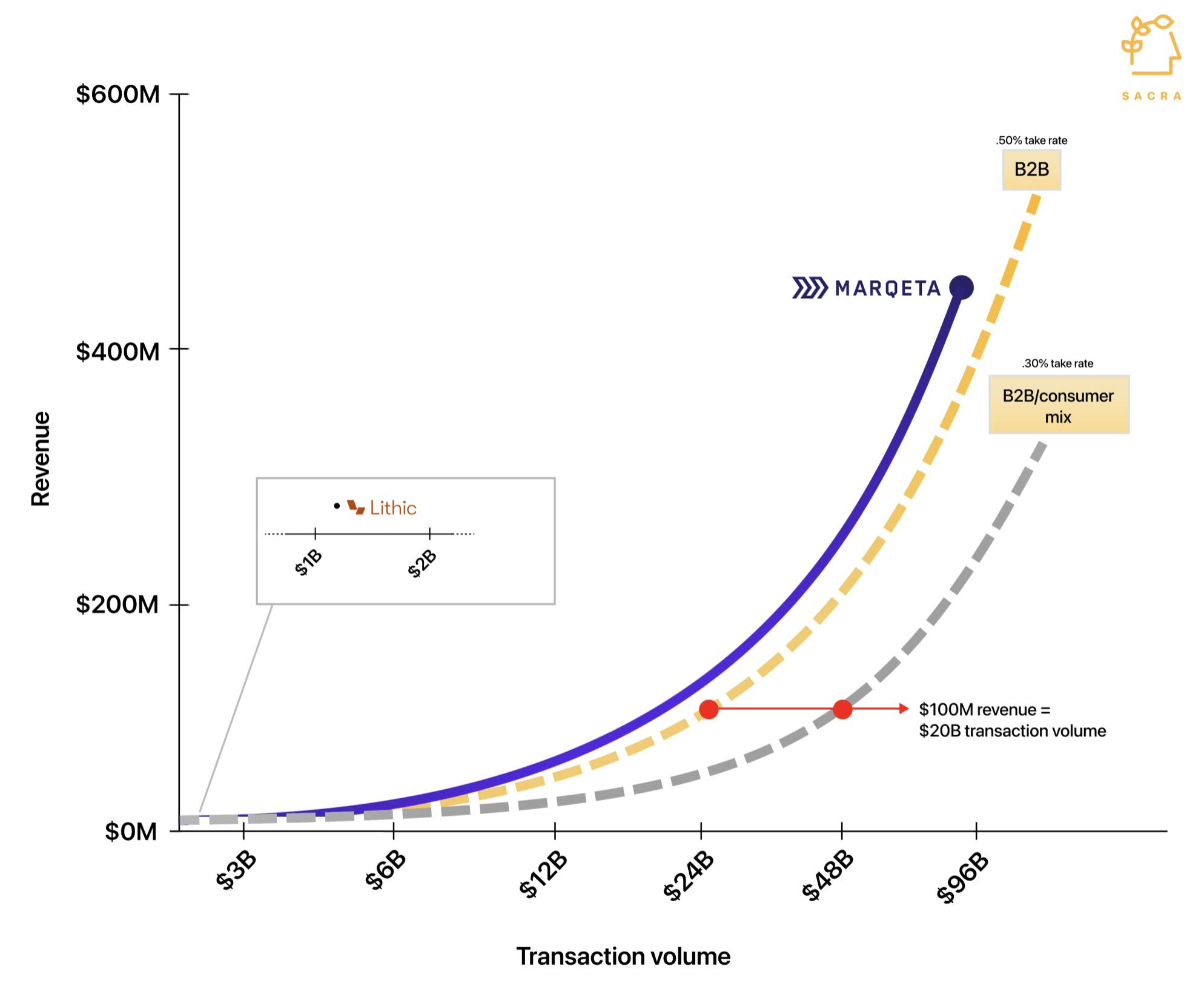

Today, BaaS companies are growing extremely fast. Early digital card issuer Marqeta hit $8B in transaction volume in 2018, nearly tripled it to $21B in 2019, and tripled that to $60B in 2020. Two distinct strategies and business models are emerging in the BaaS space, with:

- all-in-one platforms like Unit, Bond, Synctera, and Productfy that provide the widest range of different services and will tend to serve see the fastest revenue growth, albeit with the most risk around customer concentration

- point solutions like Lithic, Alloy, and Sila that solve specific problems and will tend to grow more slowly, but find more application in embedded finance and can achieve broader revenue distribution

The most important questions to ask to understand the unit economics of a BaaS business are how they make money, who they make money from, and how their margins and fees are likely to expand or compress over time as a result.

Key points

- As transaction volume goes up, the fintechs at the top of the finance stack see their portion of interchange expand, while banks at the bottom are compressed. Issuing banks go from 0.20% of interchange to 0.02-0.03% at scale, compression made possible by working with Durban-exempt sponsor banks like Evolve Bank & Trust and Sutton Bank.

- Fintechs and "embedded finance" companies like Instacart have different value propositions and grow transaction volume at different rates. The former monetize off interchange and so are incentivized to drive up volume fast, while apps like Instacart use BaaS to power product experiences and aren't optimizing for transaction volume.

- The two prevailing models in BaaS—all-in-one platforms and point solutions—carry different kinds of "build vs. buy" risk and serve different kinds of customers. Fintechs offering a wide range of financial services may get more utility from all-in-one platforms like Treasury Prime, but there will be more risk that those fintechs could take features like issuing in-house, where as point solutions helping embedded finance companies with more specific needs implement e.g. KYC will see less insourcing risk.

- All-in-one platforms have the benefit of getting closer to the customer, while point solutions can play better with other tools. Platforms can use that proximity to gather data and do more for their users, and point solutions can use plug-and-play to grow a broad customer base with good revenue distribution. We don't believe this is a zero-sum market.

- Transaction volumes across fintech, and by extension BaaS revenues, are still in their early growth stages, with card adoption today representing just 2% of global business payments. With the total global B2B payments opportunity at $125 trillion, we think the volume-based addressable market for BaaS providers is likely to be already greater than $1 trillion in total—and we expect a long growth runway to come.

How $30B+ of yearly interchange fees gets split

Banking-as-a-Service Unit Economics and TAM

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

Banking-as-a-Service Unit Economics and TAM

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

Every financial transaction, debit or credit, consists of a series of communications and handshakes between different parties.

When you decide you want to buy a Lululemon shirt via Klarna (fintech), Klarna uses Marqeta (their BaaS) to instantly issue a virtual card with a preset amount of money on it. Lululemon pays a percentage of the overall transaction amount in interchange fees to the issuing bank, which in this case would be Klarna, and an assessment is paid directly to the card network in exchange for using their payment rails.

Marqeta unbundled the role of the issuing bank, using a network of small sponsor banks to provide the actual banking while giving its customers the ability to programmatically spin up virtual cards and approve or deny their own transactions.

This enabled new features that were challenging or impossible to implement working directly with traditional issuing banks—instant issuance, specialized fraud protection, and spend controls that could be customized on a dynamic, per-transaction basis—that would become core to the customer experience of companies like DoorDash, Instacart, Uber, and others.

Where Marqeta and other BaaS companies make most of, if not all of their money on interchange: the fee set by the card networks for using their payment rails to move money.

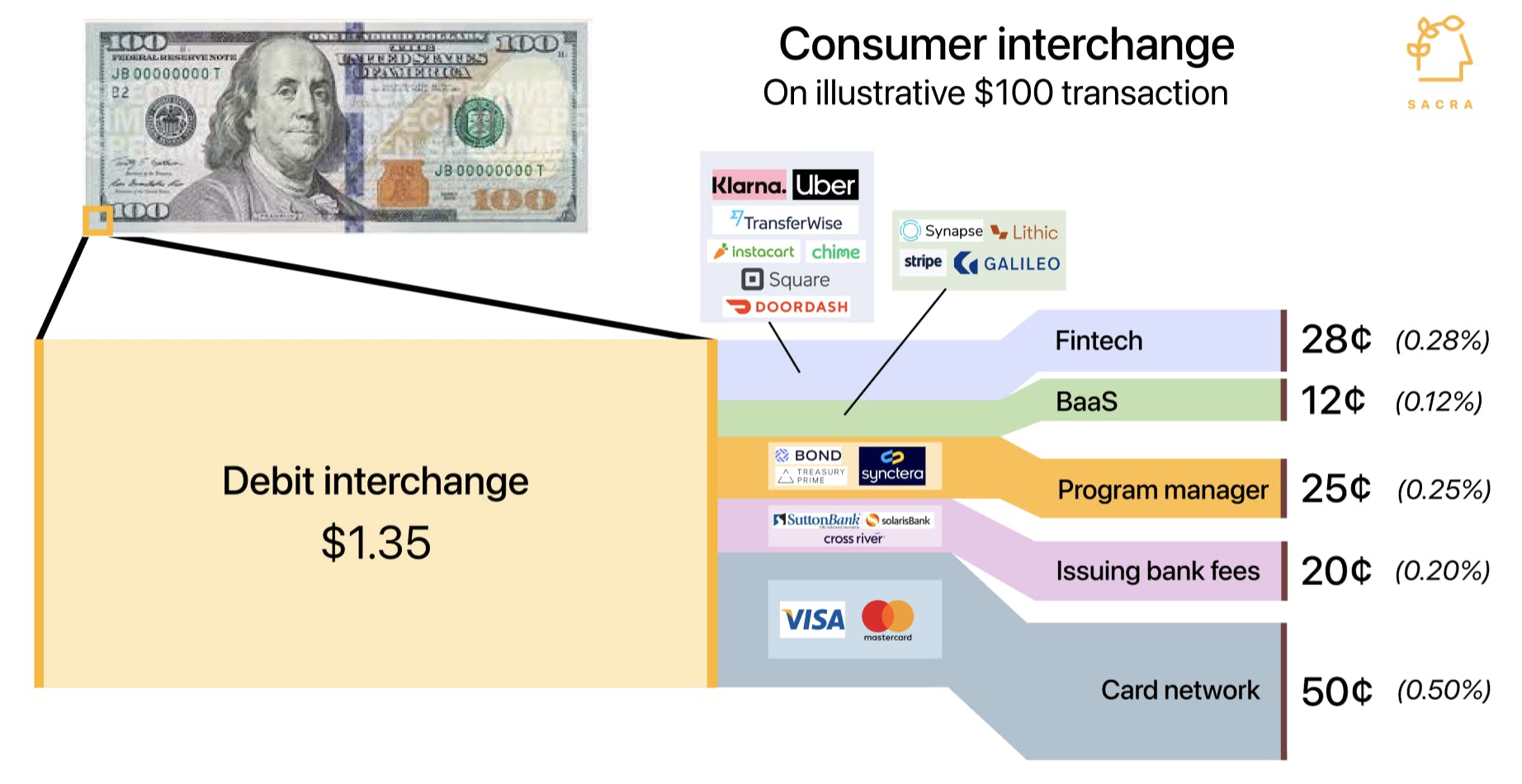

Illustrative diagram of the interchange split in a B2C transaction. (Some BaaS services can act as a program manager, for example Galileo and Synapse.)

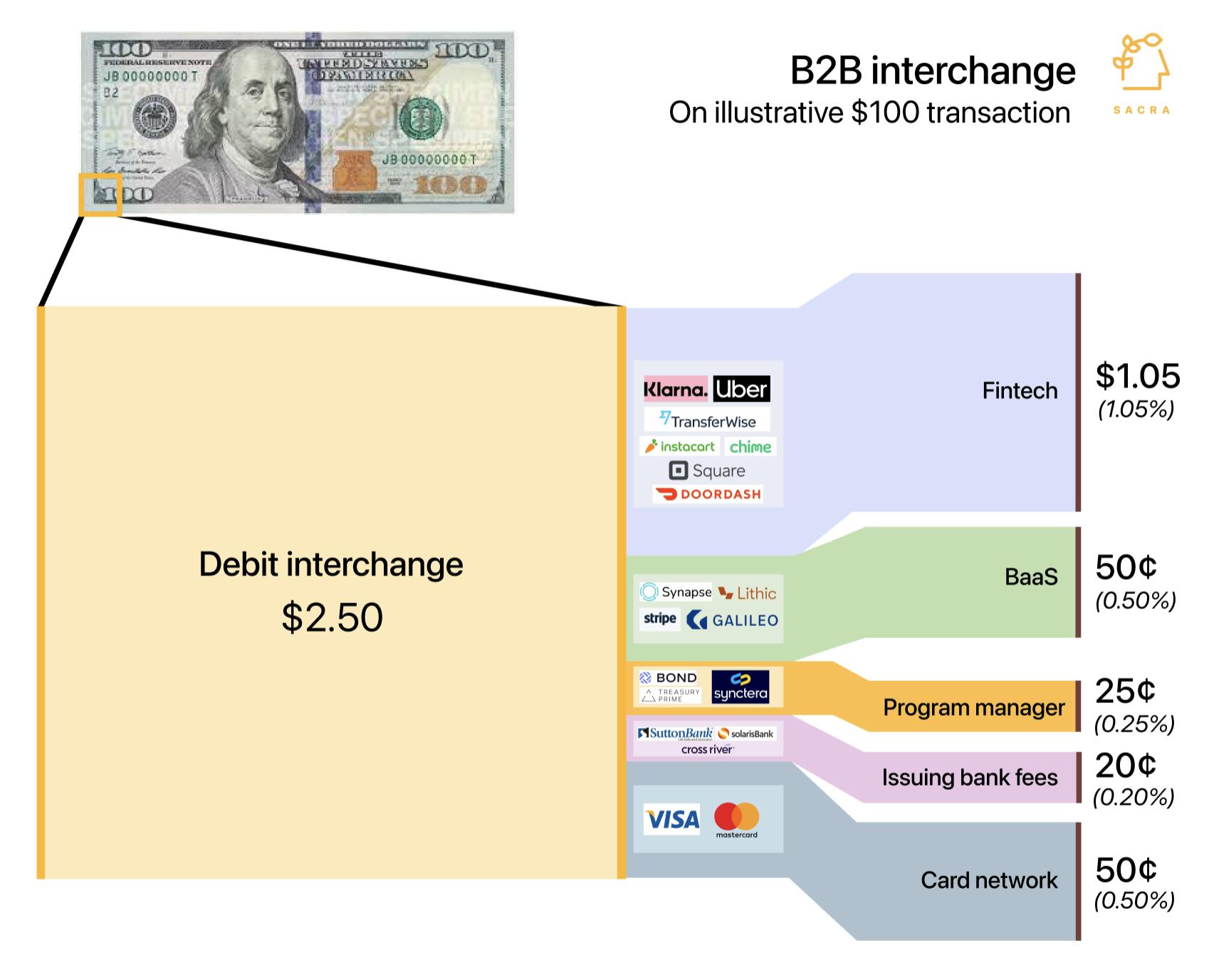

Broadly, consumer debit interchange is about 1.35% and commercial is about 2.5%. The true number is set by the card network and depends on different factors, including whether the physical card is present at the time of the transaction, the type of merchant, and others. Of that, we assume:

- the card network takes 0.5%, which tends to tier down over time as scale grows.

- the issuing bank takes 0.2%, which also trends down as volume scales up.

- the program manager might take 0.25%.

Illustrative diagram of the interchange split in a B2B transaction.

In the end, this leaves the BaaS 0.12% for B2C transactions and 0.5% on the B2B side, while their fintech customers take 0.28% for B2C and 1.05% on the B2B side.

The lowering of the bank’s take rate—from about 20 to 30 basis points to more like 2 or 3—is possible because the BaaS companies are not relying on banks like Wells Fargo but small “sponsor” banks that are exempt from the Durbin Amendment.

The Durbin Amendment requires banks that have more than $10B in assets to limit their interchange fees. Smaller banks like Sutton Bank, Green Dot, and Emigrant Savings Bank are able, as a result, to charge nearly double the fees of bigger banks, allowing them to give up much of their take rate and still get a large, asset-light stream of revenue from their BaaS and fintech partners—at least as long as this exemption remains in effect.

Why 50 basis points of interchange migrate up the stack

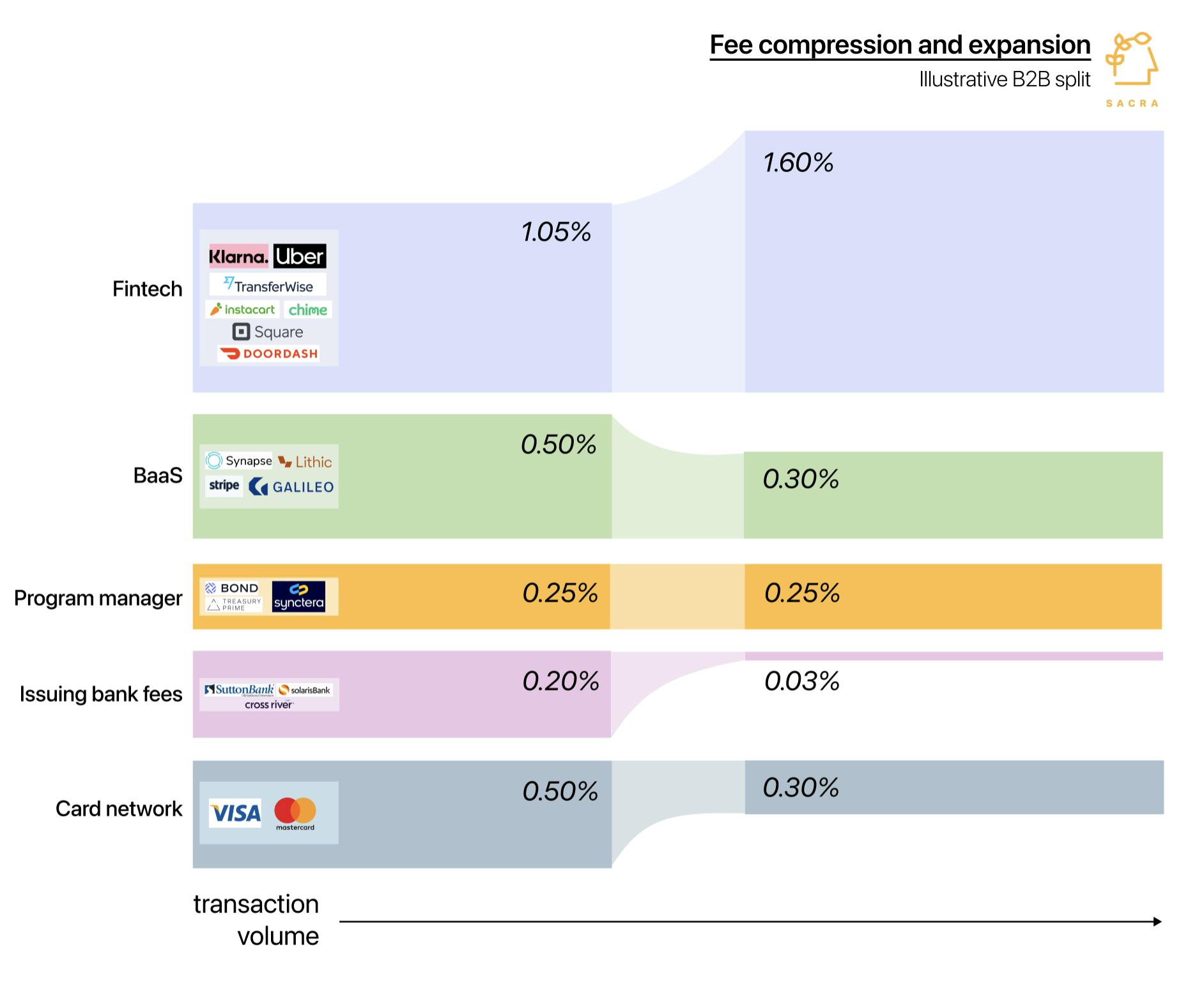

Take rates on transactions are never static—they’re constantly changing depending on factors like the type of merchant and whether the card is present or not. Take rates also change over time and at scale with changes in transaction volume and customer concentration.

As transaction volume increases, the bottom of the stack is compressed. The top of the stack—the fintech companies using BaaS products—takes the majority of the interchange.

At scale, issuing banks' fees reduce to 2-3 basis points, with the BaaS companies and their fintech partners taking more.

For the BaaS companies, their take rate relative to their customers’ could face fee compression upon contract renewal. As their customers get bigger and process more transactions, they drive more revenue. In turn, the BaaS platform might have to share some of their fee in order to keep them as a customer. Over time, this could compress the BaaS platform’s take rate, but that compression is made up for with the increase in revenue.

Because bigger customers will be able to negotiate a better take rate, customer concentration is likely to be the main dynamic in how that margin is distributed. And the primary differentiator when it comes to customer concentration is whether a customer is a fintech company or an embedded finance company:

- Fintech companies are monetizing on interchange and so are incentivized primarily to drive transaction volume up, which leads to faster growth and creates breakout winners, e.g. Square's Cash App doubling its profits in the first quarter of 2021 to $500M

- Embedded finance companies are using BaaS to drive automations and integrations that improve the product experience, not to monetize directly, meaning relatively slower growth, e.g. Instacart using issued cards to help their couriers be more efficient at the point of sale

BaaS companies serving fintech companies like Chime or Square will tend to have fewer, bigger customers and incur more concentration risk, while BaaS companies serving primarily embedded finance companies like Uber or DoorDash will typically have more, smaller customers and less concentration risk.

An example of that concentration risk aspect is Marqeta, where Square was responsible for 70% of the company's net revenues in 2020, and 73% in Q1'21. Instacart, another big customer, was responsible for just 16%.

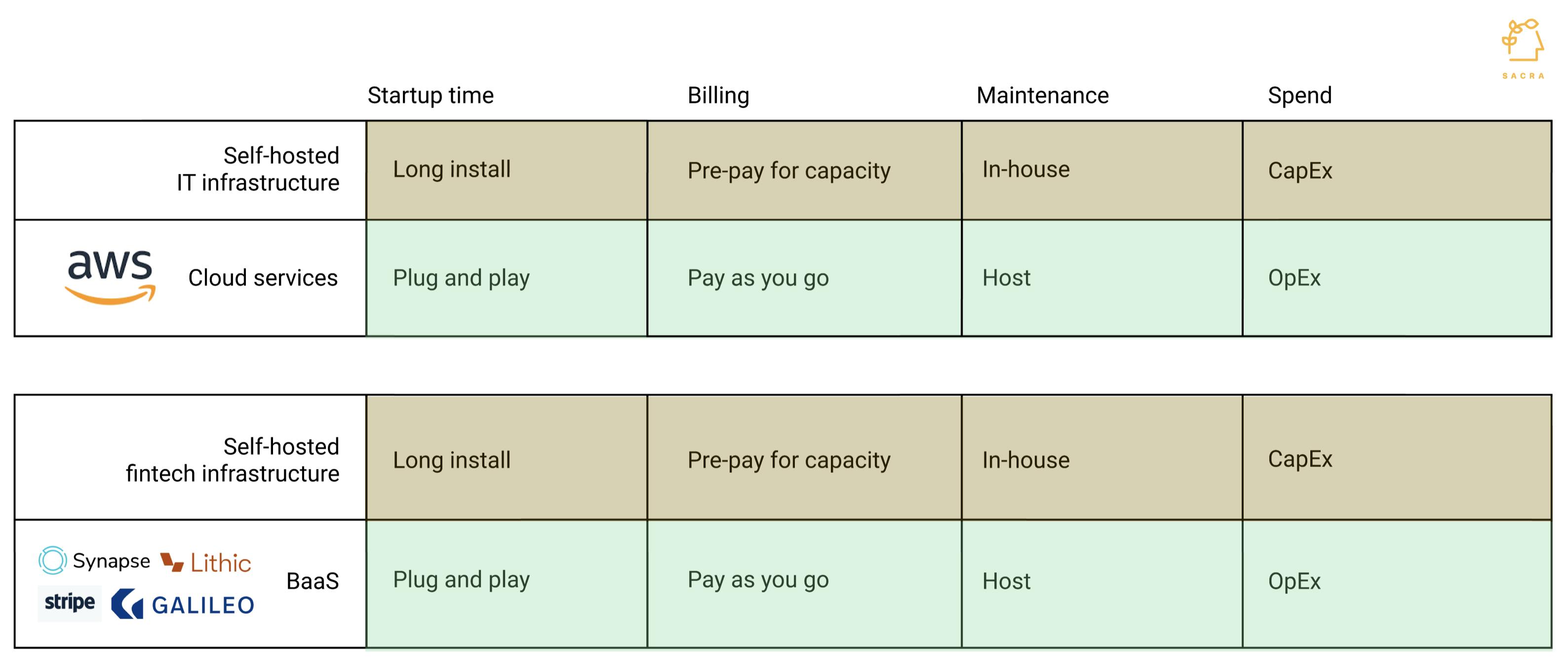

Embedded finance companies face a similar "build vs. buy" question to companies debating building their own IT infrastructure a decade ago.

The upside is that bigger companies with fintech as a core business will also tend to grow transaction volume faster and generate higher revenue growth. Those breakout winners can be huge drivers of revenue growth, as we've seen with the example of Marqeta, and can help build a BaaS company's brand and help them win the market, but it comes at a cost. Marqeta's take rate fell from about 0.7% in 2019 to 0.5% in 2020, and has dropped further since then.

Companies with fintech as a core business will also present more of a churn threat linked to the prospect of them bringing the functionality that the BaaS offers in house, similar to how Dropbox built its own storage infrastructure to save on costs at scale.

On the flip side, embedded finance companies on the other hand will tend to grow transaction volume more slowly because they're not using BaaS as a way to drive transaction volume.

Companies that are simply issuing a physical or virtual card and need a card issuing API to do so will have less complex servicing needs, bringing support and implementation costs down, and will also be less likely to bring this fintech functionality in-house, creating less risk of churn.

The $1T opportunity in rebundling and unbundling banking

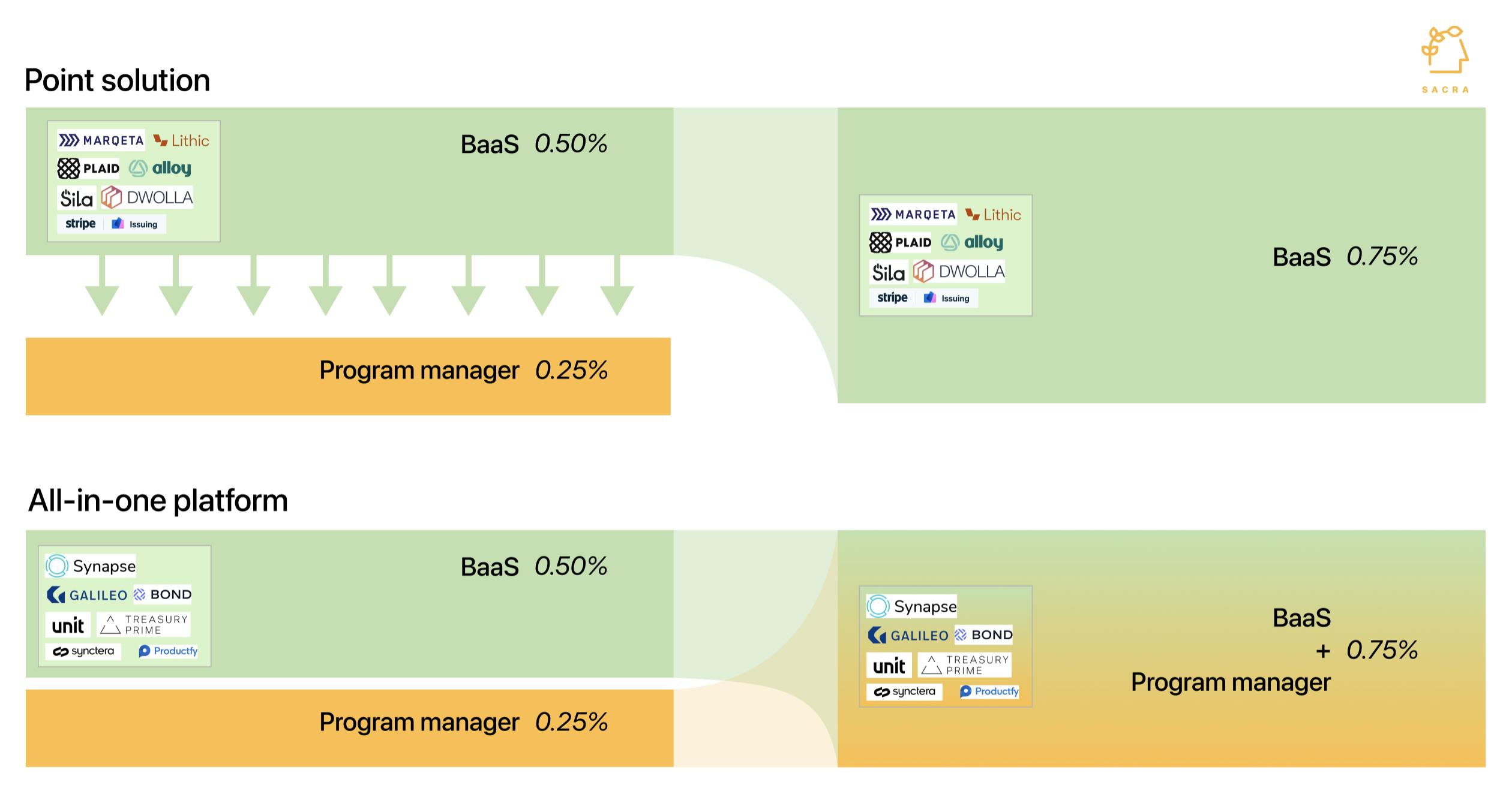

There are two basic models for companies in the BaaS space: the all-in-one platform, rebundling at the API layer the various services offered by incumbent issuer processors and banks, and the point solution, unbundling those same services and offering them up for companies to mix and match and combine as needed.

Both make it easier for companies to bring finance into their products than building it themselves in different ways. And when it comes to the unit economics of BaaS, both models have a path to win and earn themselves a larger share of interchange:

- Point solutions can grow their share by being glued together along with other services and empowering brands to build differentiated experiences

- All-in-one platforms can grow their share of interchange by creating efficiencies for their customers and generate higher margins by owning more of the stack

How point solutions and all-in-one platforms redistribute the flow of interchange.

For the platforms, the strategy may look similar to that of traditional banks. By offering everything their customers might need all in one place, they develop closeness to the customer, which gives them the opportunity to gather data and build loyalty.

On the flip side, the point solutions can enable brands to build their own financial stacks and better differentiate their user experience as a result.

It’s for this reason that the point solutions would also be incentivized both to “play nice” with other tools in the stack and provide high-quality, well-documented products that can make it easy for customers to use them without an additional coordinating layer in between.

The future of banking-as-a-service

BaaS has seen meteoric growth with the rise of modern online financial services.

The rapid growth of fintech and embedded finance has been a huge accelerant to the growth of BaaS companies, from Marqeta to the newest wave of tools emerging today.

While some of those tools—like Lithic in the diagram above—may look small today, they're growing extremely fast. They're in a market where revenue scales with transaction volume. And transaction volumes across fintech and embedded finance are still in the early stages of so-far massive growth.

Marqeta did $60B in transaction volume last year, and still, card adoption only represents 2% of global business payments. With the global B2B payments opportunity at $125 trillion, we think the volume-based addressable market for BaaS providers is likely to be already greater than $1 trillion in total—and we expect a long growth runway to come.