Banking-as-a-Service: The $1T Market to Build the Twilio of Embedded Finance

Jan-Erik Asplund

Jan-Erik Asplund

This report contains company financials based on publicly available information and data acquired by Sacra during the preparation of the report. Sacra did not receive any compensation from any of the companies mentioned in the report. This report is not investment advice or an endorsement of any securities. Find our complete disclaimers at the bottom.

Join our list for more exclusive coverage and research on the private markets.

Success!

Something went wrong...

The new banks

Over the last several years, there has been an explosion of retail, travel, SaaS, and other companies expanding into financial services.

Walmart, IKEA, ServiceTitan and Toast are just 4 of the companies that have launched products like underwriting, interest-free credit, payments and bank accounts in an effort to provide a better experience to their customers and get closer to their wallets.

Leveraging their reach and data, brands are able to do something with these products that traditional banks like JPMorgan Chase or Bank of America or Wells Fargo have never been able to: deliver personalized experiences at scale and at the point of sale.

Where banks provide a highly regulated and repeatable set of products, brands and fintechs can harness demographic and behavioral data to build new kinds of product experiences that ultimately bring them closer to consumers.

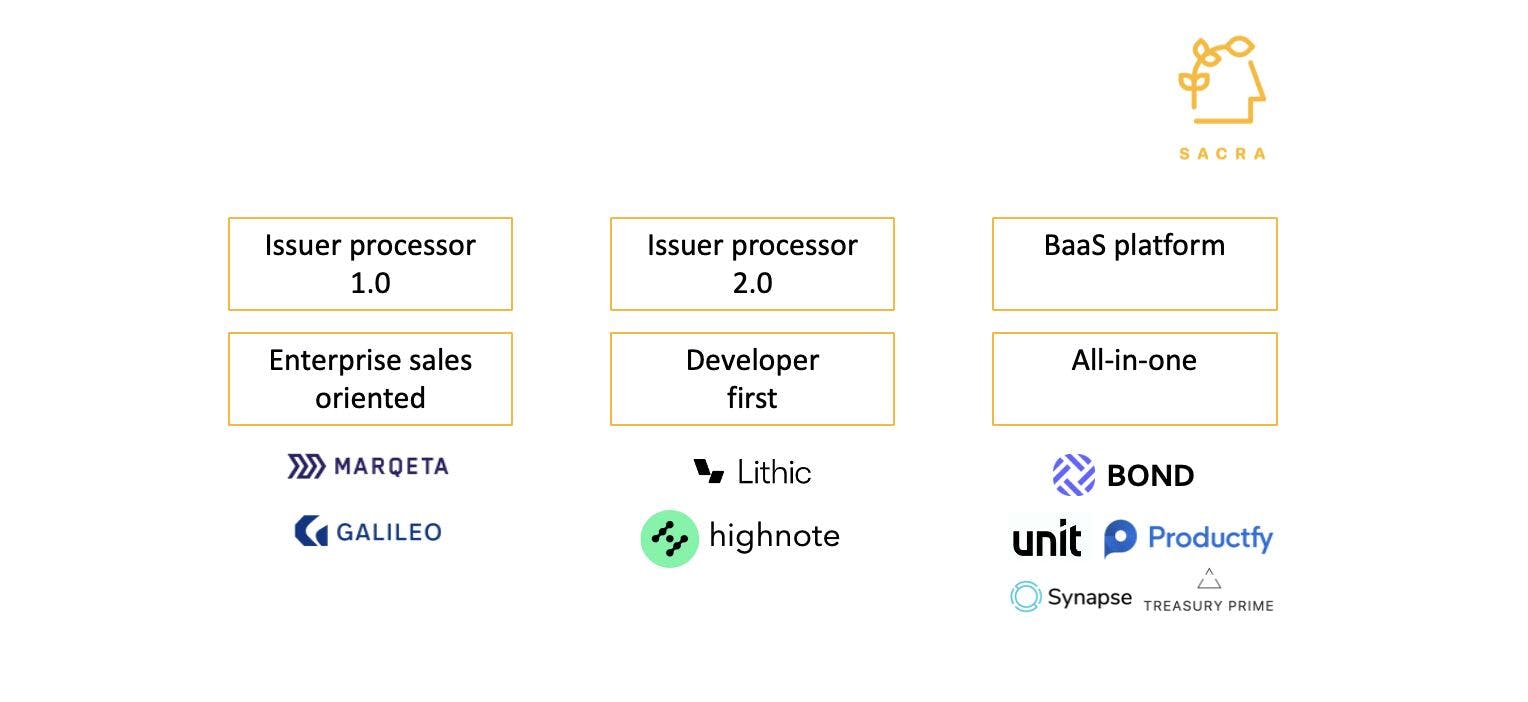

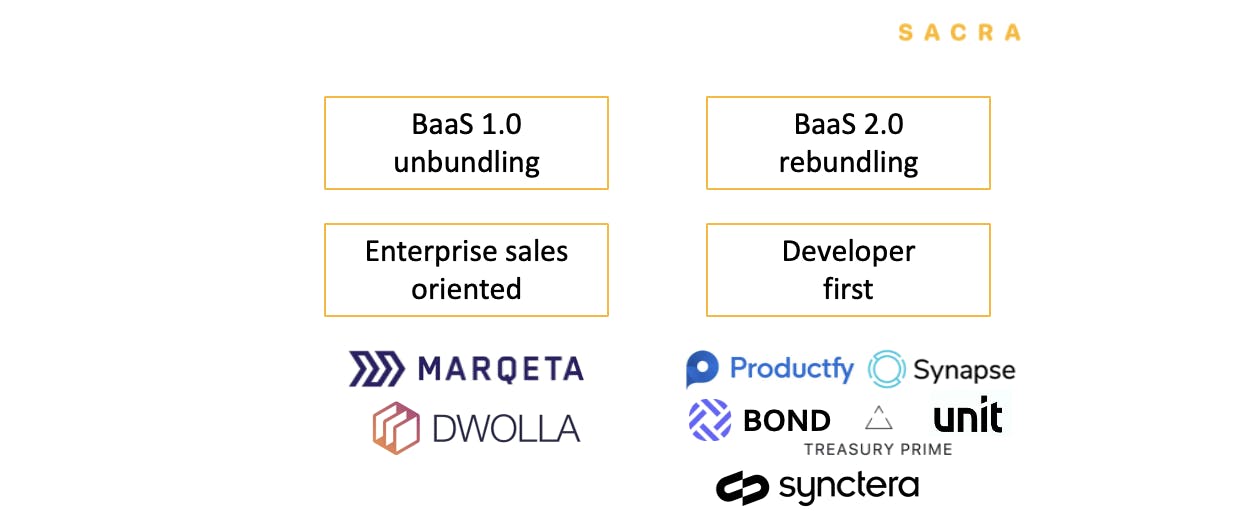

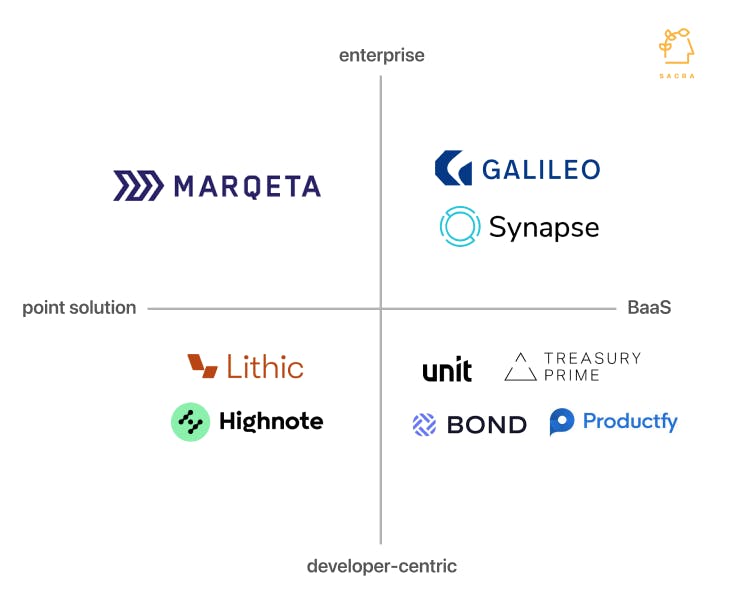

We broadly organize the relevant companies in this space into three buckets:

- Issuer processors 1.0: Companies like Marqeta and Galileo which provide API-first card issuing and processing.

- Issuer processors 2.0: Companies like Lithic and Highnote that bring card issuing to the long tail of developers instead of focusing on enterprise sales.

- All-in-one BaaS platforms: Companies like Bond, Unit, Productfy, Treasury Prime, Synapse and Synctera that offer compliance and operational heavy-lifting and assemble banking license providers, card networks and third-party issuer processors to provide a one-stop experience for fintechs and brands.

Card issuing-—the job of issuer processors—sits at the center of BaaS, because without cards, companies have no payments or accounts. Here, you have companies like the $12B Marqeta ($MQ) challenging legacy payment processors like Jack Henry, TSYS and First Data (Fiserv).

While those legacy providers are still responsible for the vast majority of B2B and B2C payment volume, digital issuer processors like Marqeta have come to power core product experiences for companies worth billions in market capitalization: fintechs like Klarna, Chime and SoFi and brands like Walmart, Apple, Uber, and DoorDash.

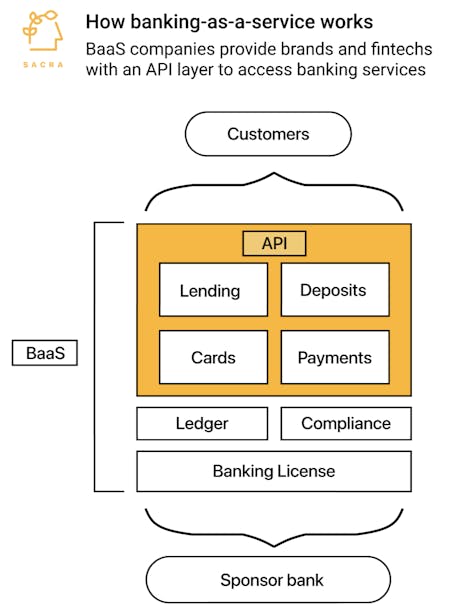

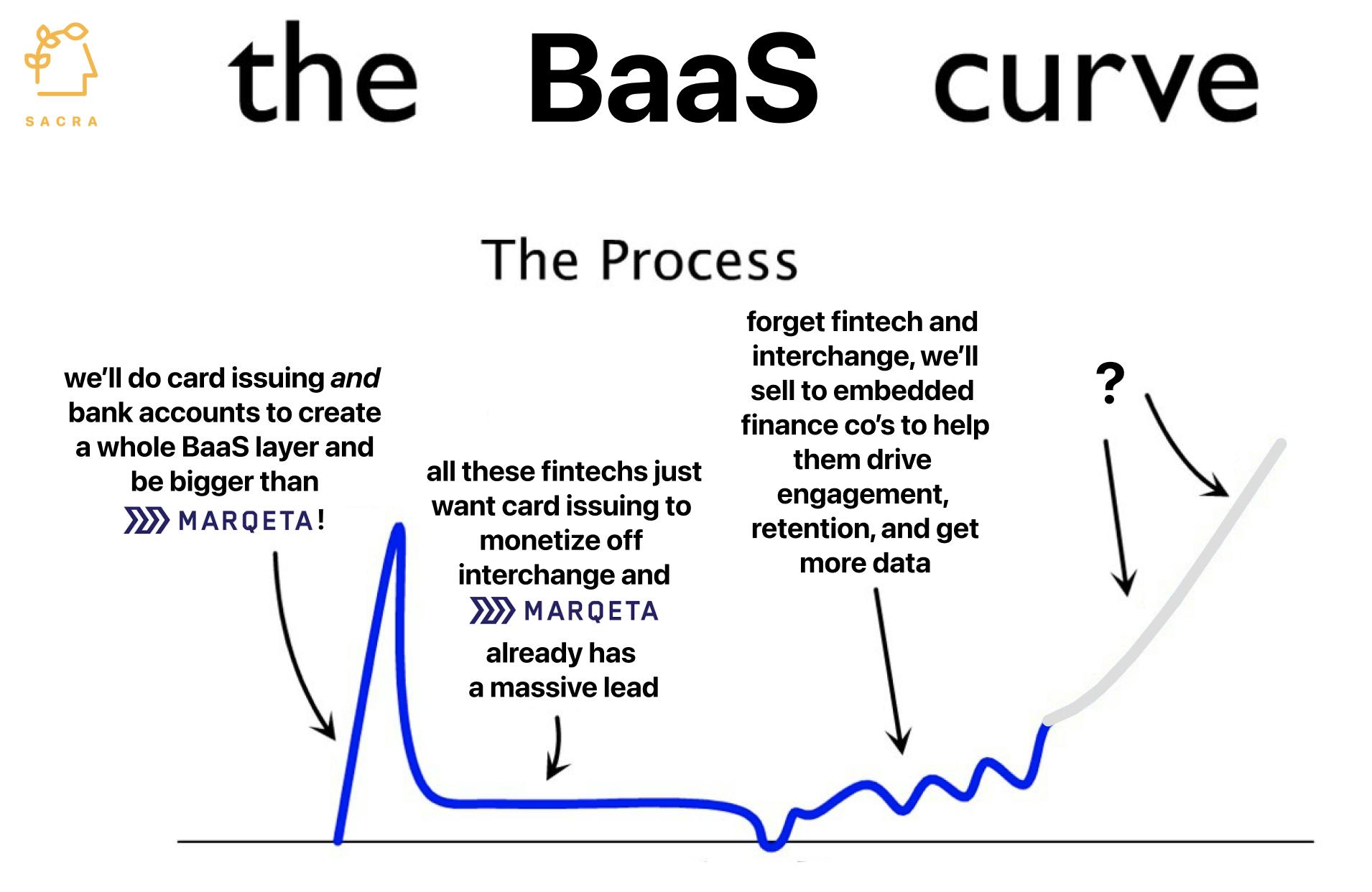

As banking platforms around the world have opened up their APIs and banking itself has gone looking for new distribution channels, a new generation of “BaaS” companies has risen to take the premise of Marqeta one step further—offering not just cards but lending, crypto, deposits, and other banking products as a service.

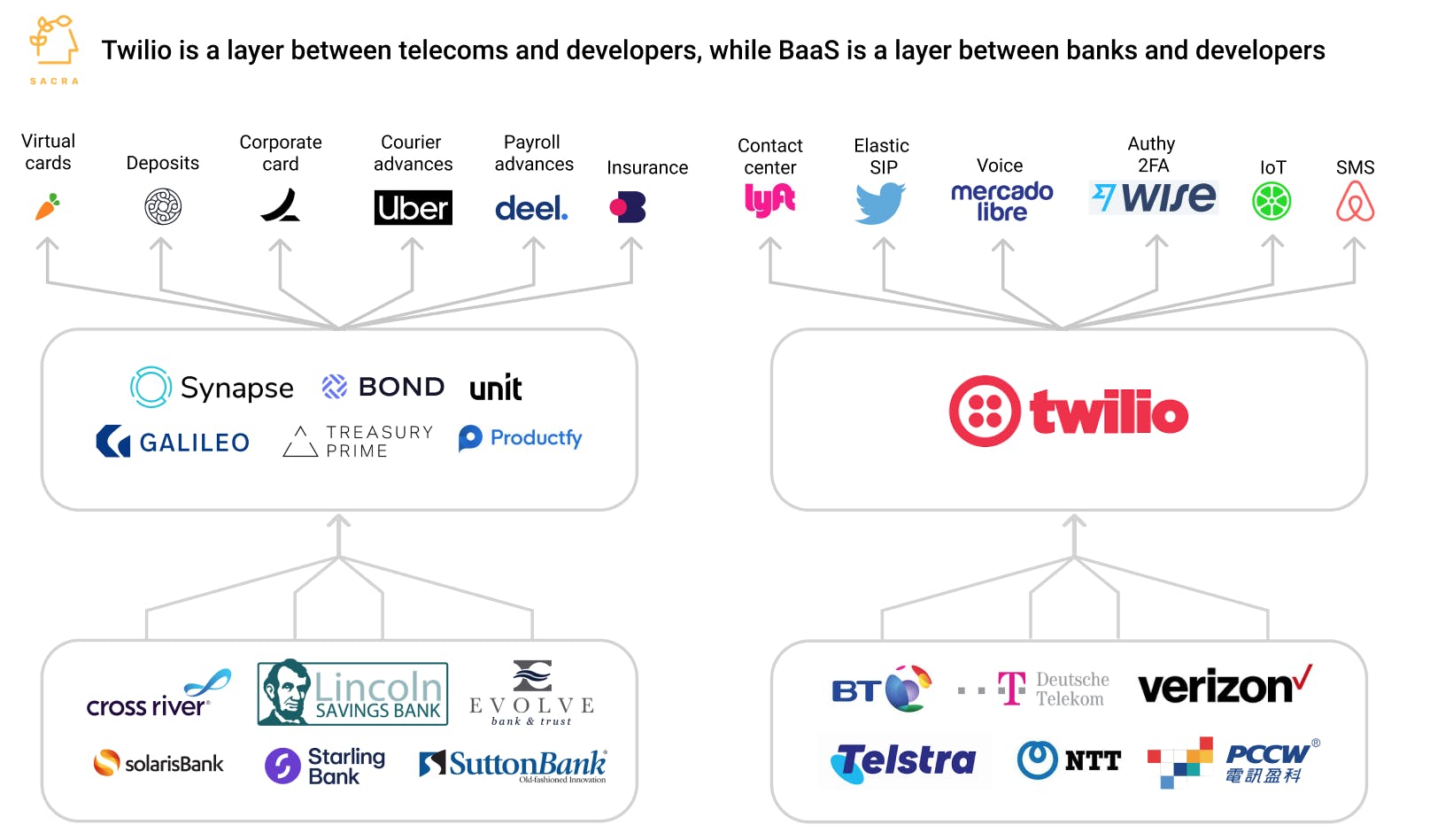

Twilio CEO and co-founder Jeff Lawson has said that Twilio “acquires developers like consumers” and enables them to “spend like enterprises.” Banking-as-a-service represents a similar mentality, ported to the world of financial services.

And just as the rise of Twilio corresponded with the rise of both mobile and the cloud, the rise of BaaS is happening amidst the emergence of embedded finance: companies using card issuing not to drive revenue, but to provide automation and richer feature sets within apps for better retention.

Twilio placed a bet on telephony becoming critical for developers everywhere, whether their app was centered around the idea of communication or not. Today, Twilio has more than 150,000 customers across industries using Twilio’s APIs to communicate with their customers and with each other.

Embedded finance can open up a similar opportunity for BaaS, with developers enabled to spin up features like courier cashout and POS advances without spending weeks and months and millions of dollars getting it done through traditional channels, and where companies like Unit, Bond, Treasury Prime, Productfy and others have the potential to both fuel and capitalize on this transformation.

Key points

- The forerunner of banking-as-a-service, Marqeta, is taking on legacy payment processors like Jack Henry, TSYS and First Data (Fiserv). Offering API access to issuing processing functions and the ability to embed payments into their products faster and more cheaply enabled companies like Instacart, Uber, Doordash and others to build new kinds of product experiences.

- Banking-as-a-service is an extension of Marqeta's logic to other facts of banking. With a BaaS provider, regular fintechs and brands can start offering services like payments, lending, crypto, insurance, and others to customers within their own products.

- Both card issuers like Marqeta and BaaS companies make money from a form of arbitrage involving interchange and community banks. Because banks under $10B AUM can charge higher interchange rates, they supply the back-end and banking license to BaaS companies, which distribute their services to fintechs and brands.

- At scale, fintechs and brands grow their share of interchange while BaaS companies and their sponsor banks are compressed. The upshot for the BaaS companies and their banks is that they can better retain their customers by giving up more interchange, while driving revenue off the growth in transaction volume.

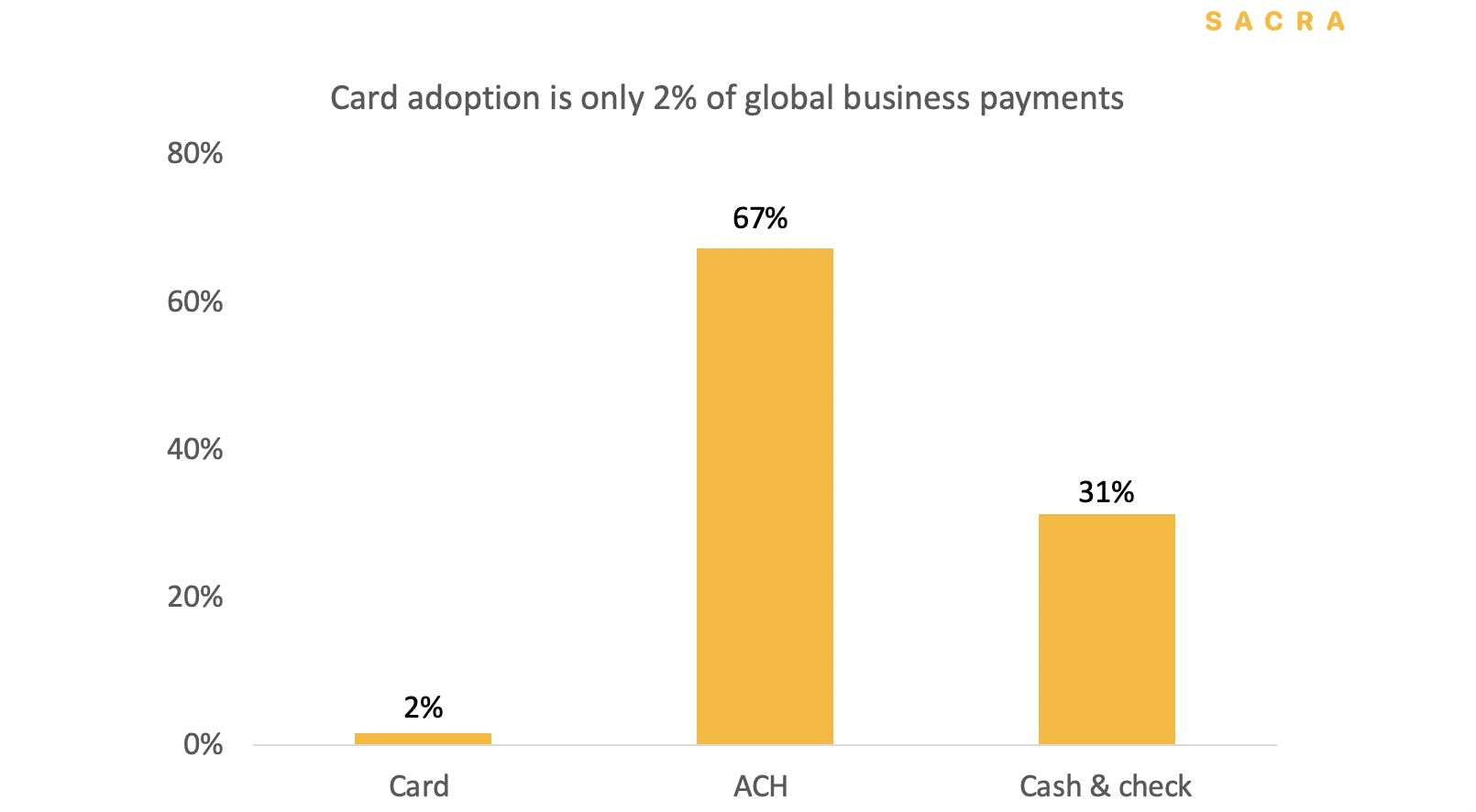

- We believe the total market today for BaaS to be greater than $1T, with a long growth runway. Total global B2B payments is sized at $125T, with just $2T of that representing card transactions. The runway for BaaS is long and we expect double digit growth into the next 5 years.

- One of the core value propositions of card issuing and BaaS is to allow any fintech to monetize like Robinhood ($38B) and hack their customer acquisition with 'free'. Instead of charging customers up front to make a transaction or execute an order, brands and fintechs can use BaaS products to offer their products for free, instead directly monetizing their transaction volume on the back-end through interchange split or balance interest.

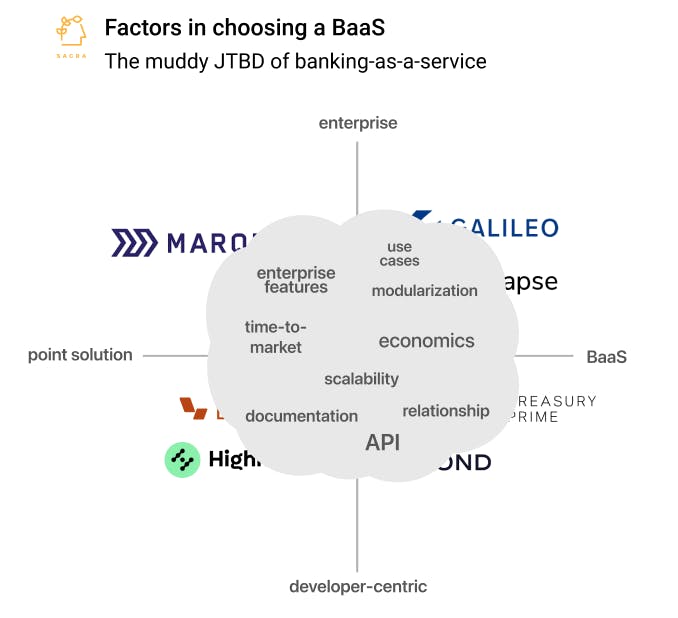

- As BaaS is still a nascent industry, categories between products are unclear and product differences are still emerging. On the flip side, brands and fintechs have a wide variety of factors that go into making a decision, between economics, speed to market, compliance, and others. One of the experts we talked to cited 200-300 different variables to consider, with "every [provider] saying the same things" in their sales and marketing.

- Marqeta's eight-year head start and dominance in the enterprise have, however, given them a powerful advantage over startup challengers. With $60B in yearly transaction volume, fintechs and brands know that Marqeta—which powers Square's Cash App—can offer them proven reliability and the ability to scale. In addition, that scale allows Marqeta to offer companies better economics on their services.

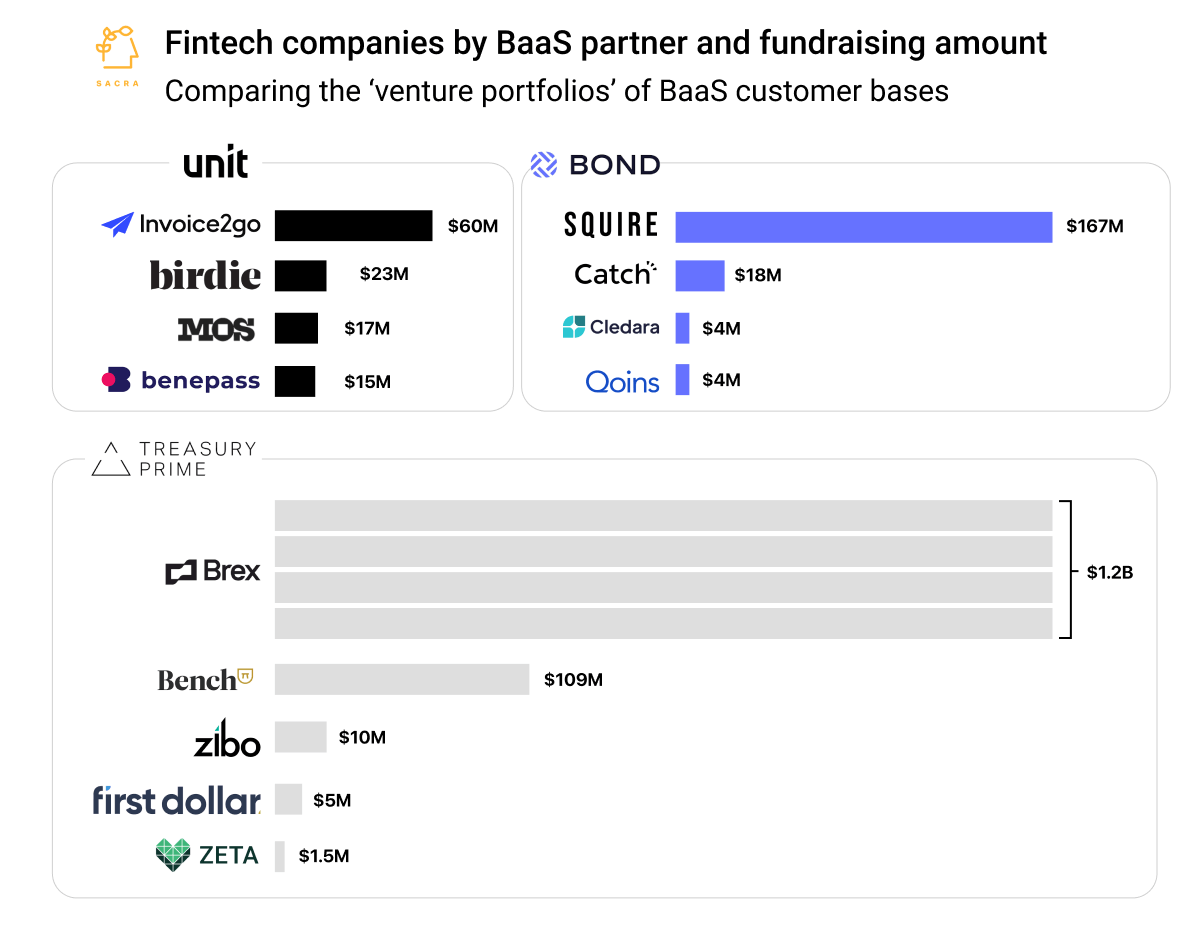

- Like Marqeta and Twilio, BaaS companies may see their revenue concentrated according to a power law, as their customer base comes to look like a venture portfolio. Ultimately, with fintechs' use cases for BaaS predicated mostly on issuing—which Marqeta dominates—BaaS is maybe best seen as a venture bet on the embedded finance space, and on a similar TAM expansion case as what happened with Twilio.

- Twilio started as a developer-centric API for texts and phone calls, but became a $55B business by enabling developers at huge, fast-growing companies to build for all their customer communication needs. The bet in BaaS is similar: that physical and virtual card issuing is just the $12B (per Marqeta's valuation) wedge into embedded finance, and that the future is one where virtually all brands offer some kind of payments, accounts, lending, insurance or other financial products to their customers.

Business model: How BaaS platforms help brands monetize

Banking-as-a-Service Unit Economics and TAM

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

Banking-as-a-Service Unit Economics and TAM

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

Banking-as-a-service platforms monetize in three primary ways:

- Interchange split

- Per account fee per month

- Subscription fee

Like traditional SaaS businesses, some platforms charge a recurring subscription fee based on the specific services and features customers want to offer, e.g. $10,000 a month for access to deposit accounts or $5,000 a month for a card program.

Others charge a per monthly fee per user to get access to the platform, tied to the number of customers that the fintech has. For a fintech with a million users and a per user fee of 10 cents, their total per user charges would amount to $100,000.

These kinds of platform fees might be more common in fintech verticals with less transaction volume, where they could be used to lock in revenues.

The majority of BaaS revenue, however—roughly 60%—comes from interchange, which is the fee set by the card networks for using their payment rails to move money, paid by the merchant, and split among the various participants in a given transaction.

It’s not always going to be desirable for a banking-as-a-service provider to increase its take rate of the interchange. Check out our interview with Productfy’s Aaron Huang for more on the regulatory risks that can make a higher take rate a liability for a fintech or BaaS company.

For an example, say you are browsing through items via the Klarna app (a fintech) and you decide you want to buy a $200 hat from a store that doesn’t have a native integration with Klarna:

- Klarna instantly issues you a virtual card with exactly $200 preloaded onto it, that will only work at the merchant of your choosing, via Marqeta (their BaaS provider)

- The merchant pays a percentage of that $200 in interchange fees to their issuing bank + their BaaS provider—here, Klarna and Marqeta

- An assessment is also paid directly to the card network in exchange for using their payment rails

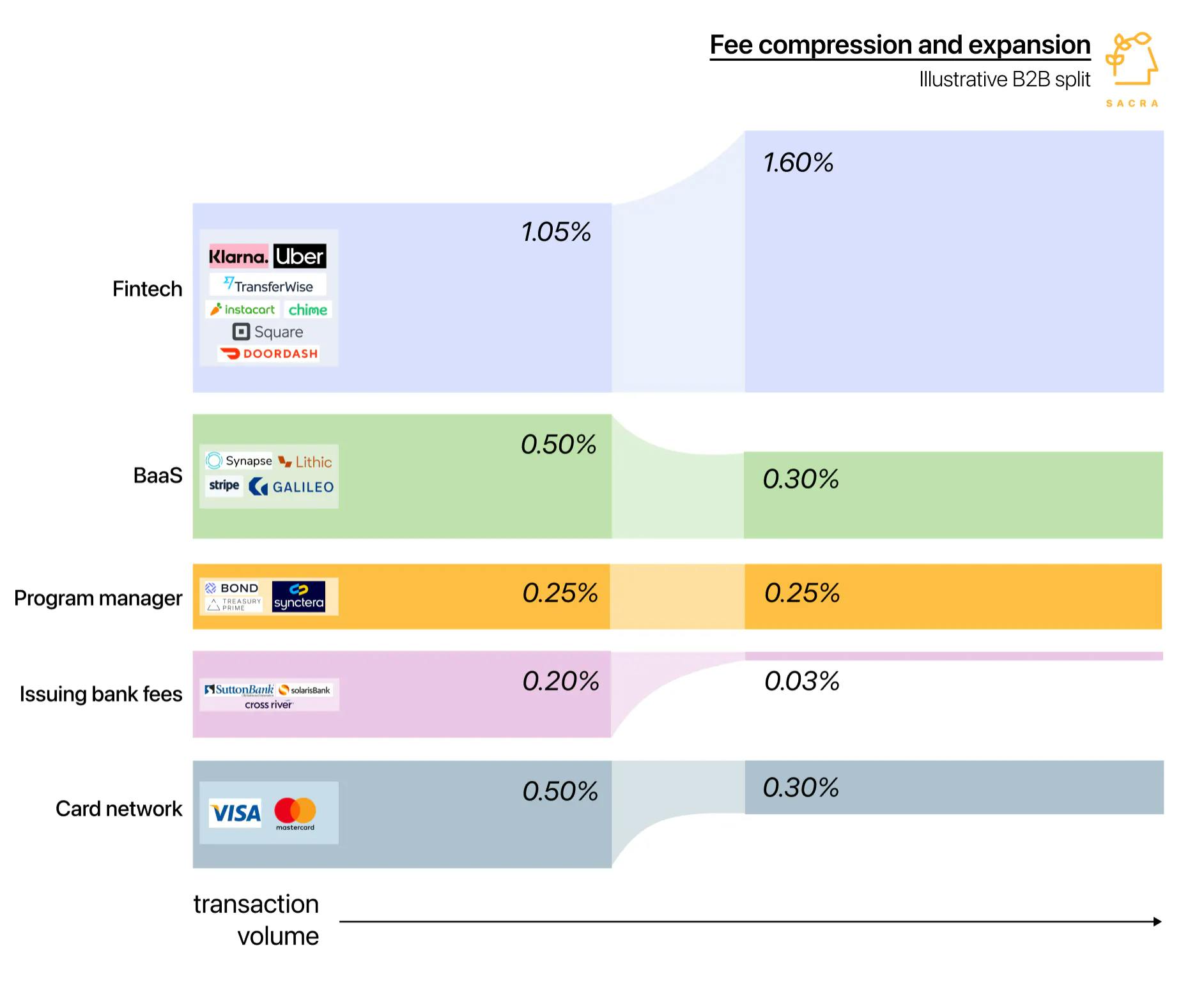

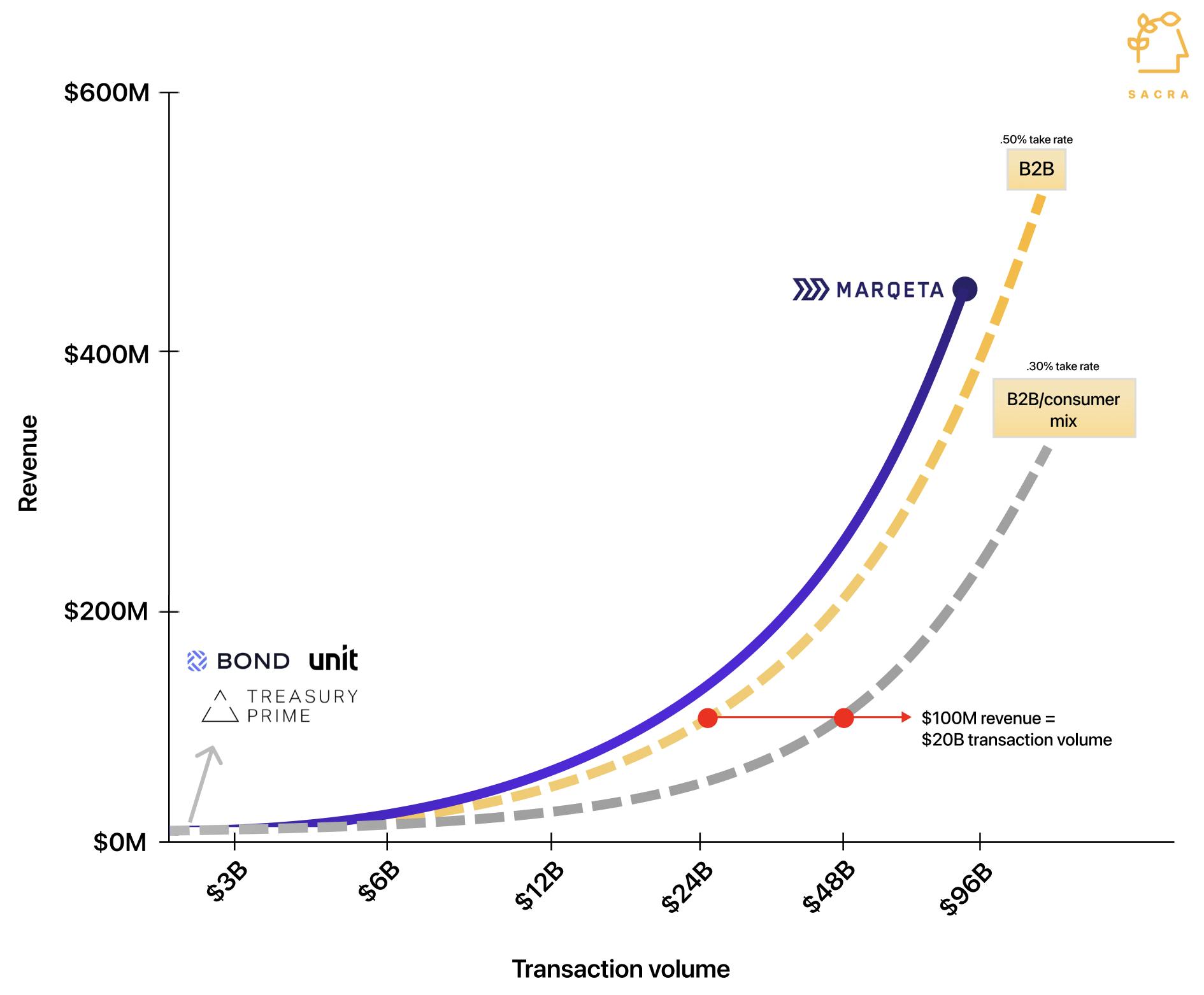

Broadly speaking, consumer debit interchange is 1.35% and commercial transaction charges 2.5% interchange. Of that, we assume:

- the card network takes 0.5%, which goes down over time as scale goes up.

- the issuing bank takes 0.2%, which also goes down as volume goes up.

- the program manager takes 0.25%.

In the end, this would leave the BaaS roughly 0.12% for B2C transactions and 0.5% on the B2B side, while their fintech customers take roughly 0.28% for B2C and 1.05% on the B2B side.

However, at scale, the bank’s take rate is compressed, and the take rates at the top of that stack can expand.

At scale, the bank take rate falls to 2-3 basis points, with the BaaS + fintech take rate going up.

These attractive unit economics are made possible by the fact that when Congress limited the interchange rates banks could charge with the 2011 Durbin Amendment, they specifically exempted banks with under $10B in assets from the changes. Working with smaller banks like Sutton, Cross River and Green Dot, fintechs and BaaS companies earn about twice as much on interchange as they would in working with a big bank.

Regardless, interchange revenue does carry risk, because regulators could end this form of “regulatory arbitrage” and make it more challenging for BaaS companies and issuer processors to build their business on interchange.

JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon mentioned the competitive threat posed by the banks and fintechs that are able to take advantage of the Durbin rules on an earnings call in January:

People who we will make a lot more on debit, because they activate under certain things, the only reason they compete is because of that. People you know, basically, don't do KYC AML and create risk for the system. And I can go on and on, but that part we will be a little bit more aggressive on, people who improperly use data has been given to them by client, OK? So you can expect that there will be other battle totake place here.

Another complication is that these take rates are not static—they change across different kinds of transactions and at scale, with changes in transaction volume and customer concentration.

BaaS companies could see their take rates compress as their customers get bigger and process more transactions, though they will also see increasing volume, and the problem could be exacerbated with high customer concentration.

TAM: The $1T market for banking-as-a-service

The global B2B payments opportunity alone has a size of about $125 trillion, with carded B2B payments representing about 2% of that or $2 trillion.

We believe the volume-based addressable market for BaaS providers today is accordingly likely to be greater than $1 trillion.

Further, we expect this market to continue to grow in at least the high double-digits for the next 5 or more years.

There are a few key factors in the growth of BaaS: the ongoing shift from cash to card spending across both consumer and business, market share gain, and the expansion of its TAM from the growth of embedded finance.

- Top-line growth: Marqeta grew 90% per year over the last 3 years in large part due to the growth acceleration across its customers.

- Market share gain: BaaS’s abstraction of banking functions is enabling new kinds of expense management and financial planning for companies—across these and other markets, BaaS can become more and more influential

- TAM expansion: As usage of embedded finance trickles down from fintechs to businesses like traditional retailers, car dealers and your local sports team, the number of potential customers will undergo a massive increase.

Near-term addressable payment flows for BaaS include B2B, personal consumption expenditure (“PCE”) and payouts. Medium-term payment flows include credit card processing and cross-border payments.

We think long-term, secular growth in BaaS comes from both mix shift (from cash to cards) and the TAM expansion of embedded finance.

Analysis: How BaaS becomes the Twilio of embedded finance

In the past, the only way to extend financial products like cards or bank accounts or loans to your customers was to spend years and millions of dollars becoming (or trying to become) a bank yourself.

As late as 2014, if you didn’t have a bank charter, issuing any kind of virtual cards to your customers meant you would have to work with a legacy processor like i2c, FIS, TSYS, First Data (Fiserv), or Jack Henry.

Getting a product to market with those providers could take a year or more, $500,000+, and a large amount of work on the engineering side.

Marqeta, the first major player in this space, partnered with a bank, built card rails, integrated with Visa and MasterCard and other card networks, and built themselves into the first modern digital issuer processor. They made it possible not just for other fintechs but for non-fintech companies to bring cards to market.

Banking-as-a-service took this idea and broadened it such that companies could access all kinds of financial functions via API.

Treasury Prime, Bond, Unit, Synapse, Productfy, and other BaaS providers serve as all-in-one banking platforms, encompassing card issuing, payments, bank accounts, lending, and more.

In doing so, they both facilitate companies quickly spinning up sophisticated finance products, and they drive more business to infrastructure-level companies like Marqeta, as well as upstarts like Lithic and Highnote, which they use to power their offering.

These companies emphasize a modular approach that permits integration with other tools so companies can essentially build their own BaaS stack: Alloy for KYC, Sila for ACH, Lithic for card issuing, Canopy Servicing for lending, etc.

For companies today, because of these banking-as-a-service companies and digital processors, offering banking services has become something that companies can start doing in a matter of weeks.

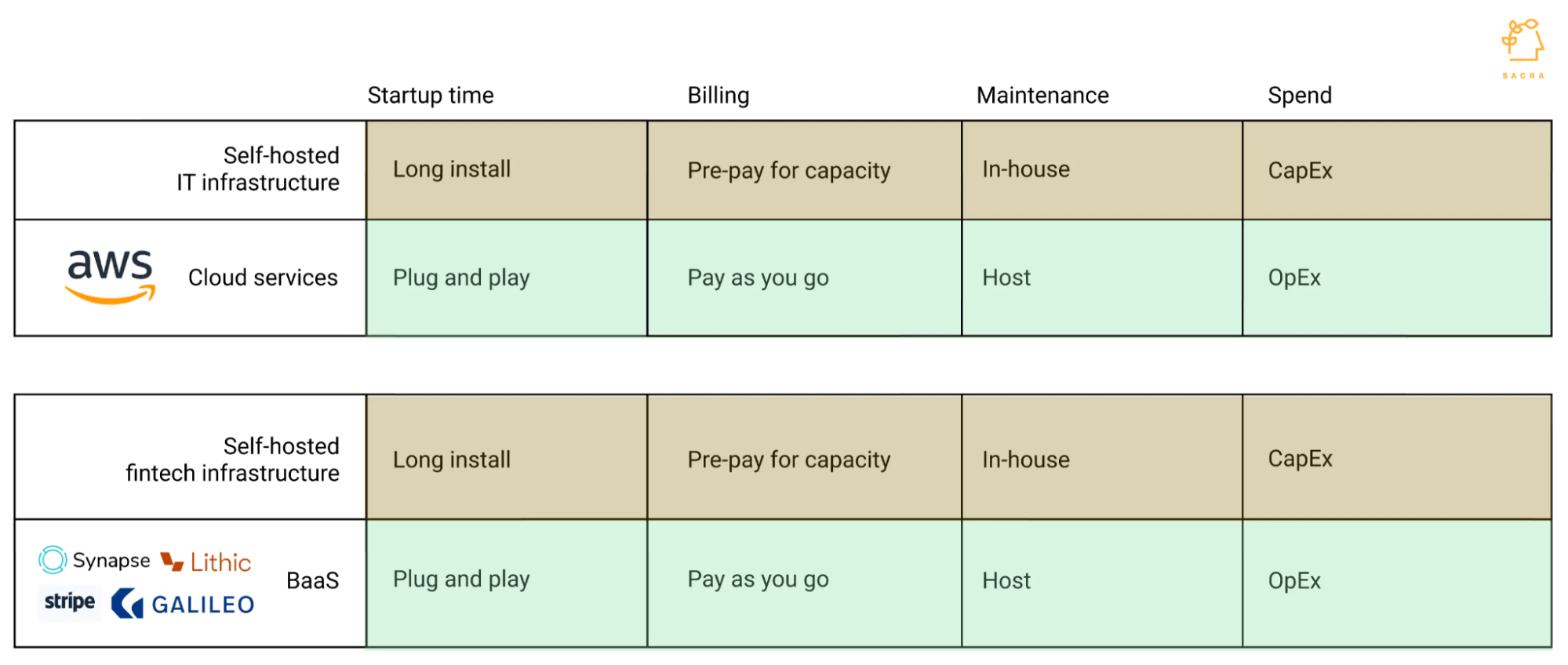

Reminiscent of build vs. buy debates around cloud infrastructure, these companies bring a leaner, more opex-centric approach to financial services that moves faster and is more flexible to customer needs.

They make it possible for companies that never could have monetized off interchange to do so, but importantly, they also enable companies that never could have issued cards to incorporate them into their products.

That’s driving a rise in two phenomena: a broader range of more specialized fintechs using banking services to monetize, and everyday apps you use like Instacart and Uber using banking as a part of their core product experience.

One of the big questions for BaaS platforms today is which of these two segments they will serve.

1. How BaaS enables fintechs to monetize on the back-end like Robinhood ($38B)

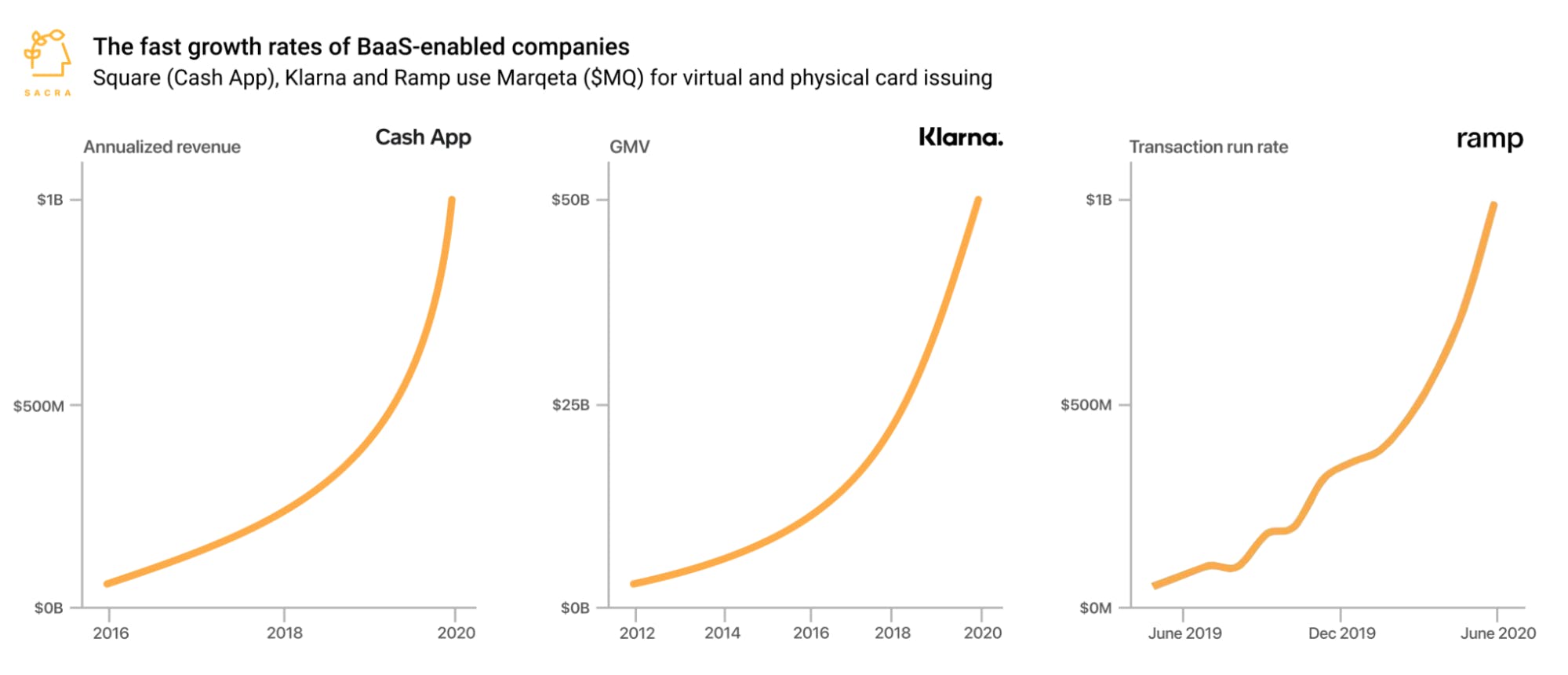

Square and Klarna are two fintech companies that have had dramatic growth stories over the last decade. Cash App went from $100M to $1B in annualized revenue in 2.5 years, while Klarna has grown to $53B+ GMV from just $15B in 2016. Ramp, while much newer, has also grown extremely fast, crossing $1B in transaction volume in around a year after launching.

Behind all three of these companies is the digital card issuer and forerunner of this generation of banking-as-a-service products, Marqeta.

Marqeta allowed Square to offer its users a virtual Visa card that they can use to make purchases using the funds in their account. It allowed Klarna to offer its users a virtual card that they can use to make BNPL purchases, and it allowed Ramp to issue corporate cards that hook up to their expense management platform.

And while Marqeta was useful for building these product experiences, the deeper insight was that card issuing could serve as a new form of—free—marketing and customer acquisition.

By giving companies the power to monetize on interchange, Marqeta allows products to be given away to users, not charged for. Companies can recoup their costs, instead, on the back-end, where they monetize merchants—not their customers.

That makes card issuing not just a feature but a way for companies to reorganize their business models around interchange: something that has had big implications for Square, Klarna, Ramp, and many other companies.

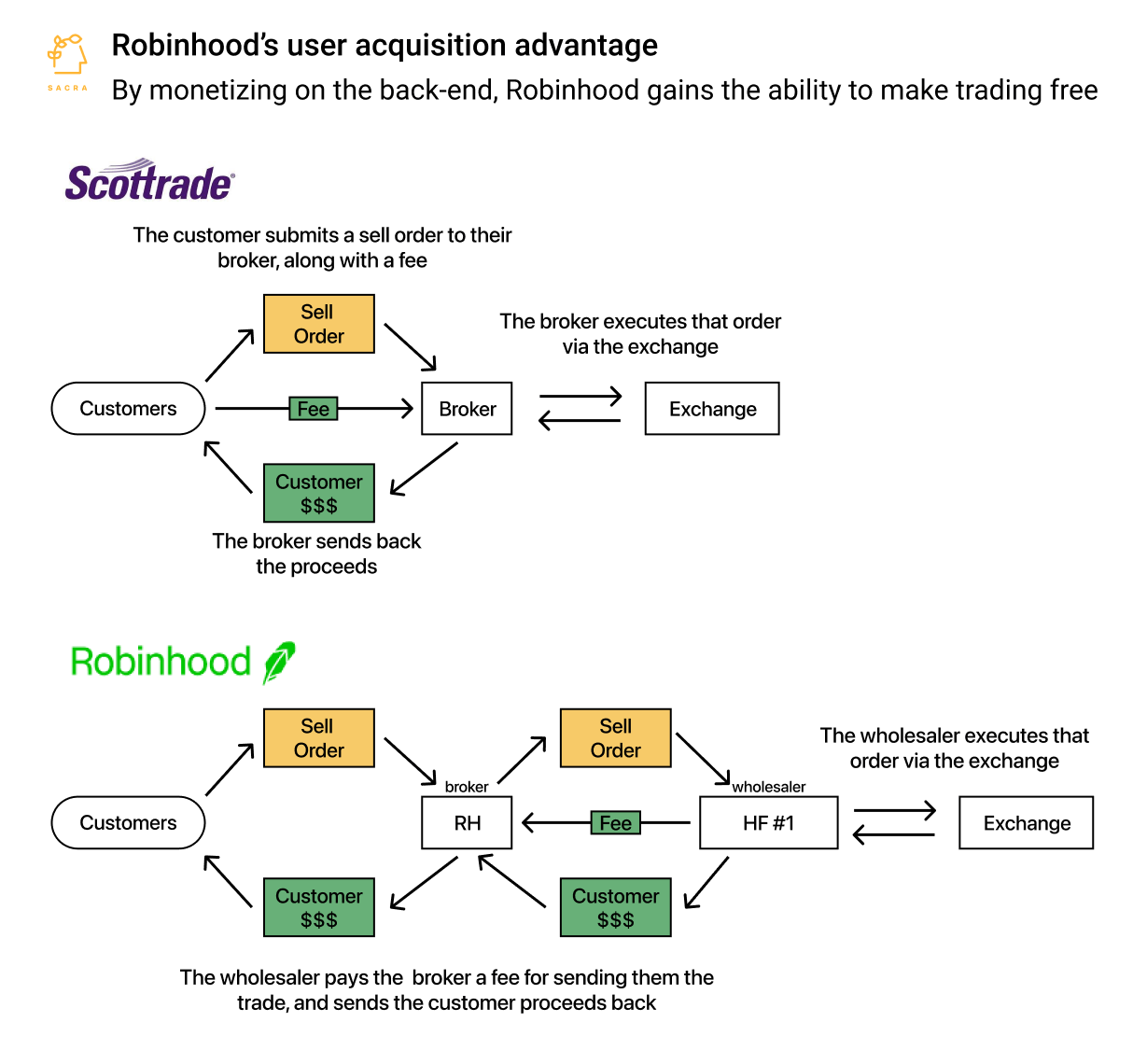

There’s a kind of parallel here to Robinhood, the $38B trading platform that brought the idea of zero-commission trades (easily available through mobile app) to the public.

Robinhood could fund all that zero-commission trading because of their backend business model of selling their customer’s orders to third parties, or accepting payment for order flow.

In that case, the third-party market maker paying Robinhood to execute its orders is generating the revenue—in the case of card issuing, it is the merchants paying the interchange fees who are generating the revenue. In each, the burden of paying for the service rendered is moved off of the customer, creating the appearance of ‘free’.

Similarly, a company like Ramp, instead of charging corporate customers a fee for using their card and attached expense management platform, can monetize the transactions and get paid alongside the card network and issuing bank. That allows them to use the very enticing value proposition of free to gain more customers, which generates more transaction volume and more interchange revenue.

This business model innovation was massive for Robinhood’s business, and the ability to monetize on interchange is central not just to Marqeta’s business but to the businesses of their customers.

As Pry's co-founder and CEO told us, "interchange pricing is great. The end-user has no idea about pricing, so they feel like it's cheap. But you're making a lot on the backend."

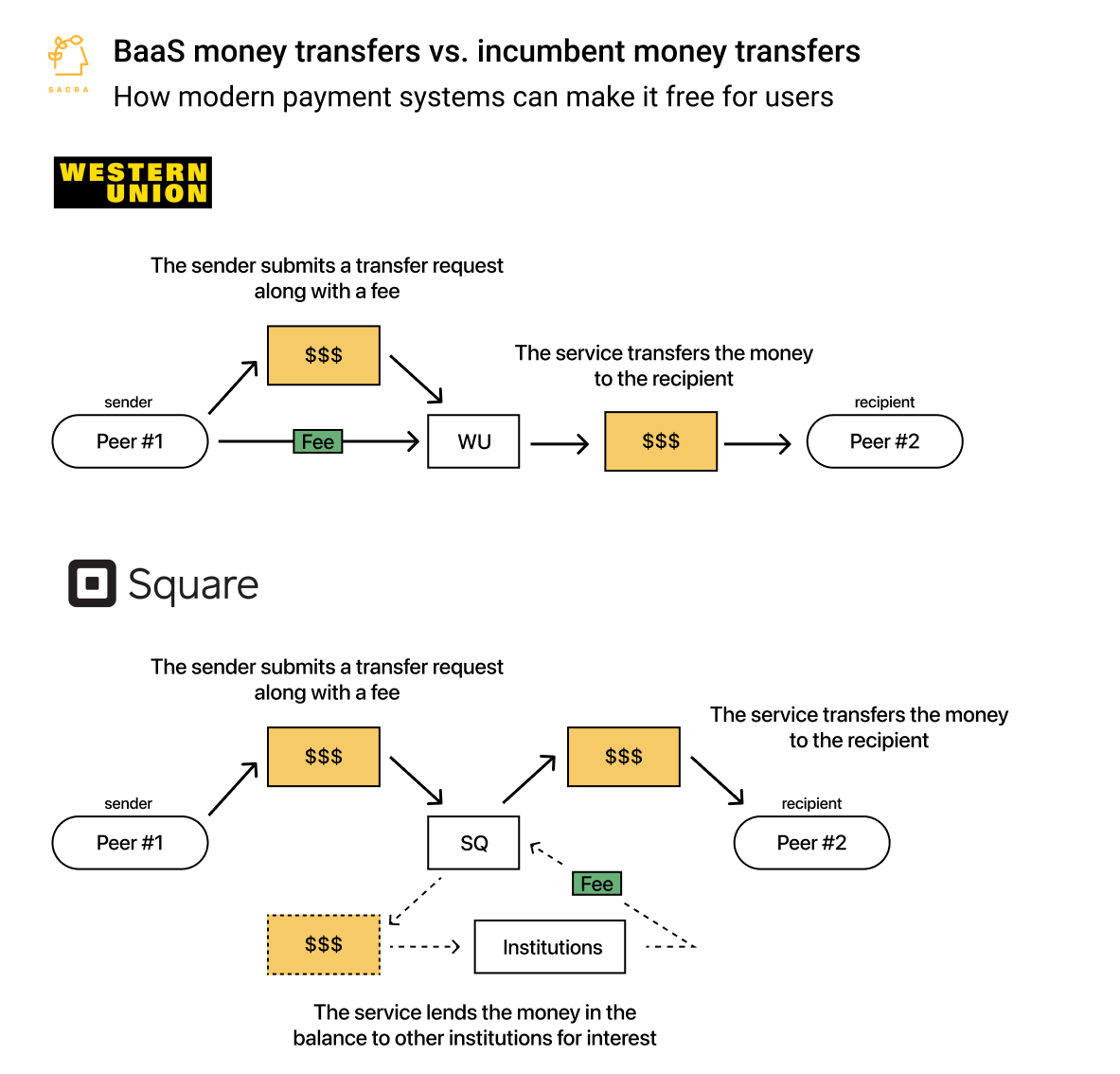

This innovation has also helped usher in the rise of BaaS. The difference is that with banking-as-a-service, companies can look to monetize not just on card issuing but on other banking functions like lending. It’s the same kind of shift in business model, only widened.

With BaaS, the number of potential business models for fintechs and brands expands again—not only can they collect their revenue on the interchange from cards, but they can execute on crypto arbitrage or, as in the above diagram, lend out user account balances to other financial institutions and collect interest.

2. Marqeta ($12B): BaaS’s 800 pound gorilla in the room

Marqeta’s developer-friendly digitization of card issuing, and the potential business model innovation that it fostered, has given way—years later—to a rich ecosystem of products.

Within the world of BaaS and card issuing, you broadly have four overlapping categories of companies:

- Enterprise: focused on selling top-down into big companies and fintechs

- Developer-centric: focused on bottom-up self-serve adoption

- BaaS: a platform that provides a wide range of banking functions via API

- Point solution: a tool that primarily provides an API for one use case (i.e. card issuing)

Early platforms like Marqeta, Galileo and Synapse targeted the enterprise—the former with a point solution around card issuing, the latter with a broader platform. The enterprise was, at the time, likely the best place for these companies to find customers with the actual time and resources to put together a virtual card program or lending service.

Today, these are massive companies that serve a mere handful of customers—Marqeta, for example, only has about 160 companies that use its product—but with very high ACV. Marqeta generates $488M in yearly revenue for approximately $3M from each customer.

In recent years, we’ve seen the emergence of more and more developer-centric, bottom-up platforms that look to sell card issuing and BaaS via a self-serve sales motion.

The idea is to make it as easy as possible for developers to start building products with their platforms, with the end goal being—like Twilio—to then capture those customers and capitalize on their growth as they scale.

One key caveat here is that banking-as-a-service is only a few years old as an industry. In practice, these clear distinctions tend to get muddied as companies consider the range of different variables that go into choosing a BaaS provider or card issuer.

As the interview excerpts below show, these categories are not set in stone, as most players are still looking for a way to differentiate. Additionally, brands and fintechs are making decisions between BaaS providers as much on the basis of their service and support capabilities, teams, and sponsor bank relationships as they are on any 1:1 feature comparison.

Well, obviously the economics. But even more important for us at this stage, is the speed to launch, which is why Lithic, previously Privacy, is so interesting. Stripe is interesting… And then the economics will make us stay with someone if it does work out…[but] what might hold things up is the KYC process. That's the top thing on my mind because we want to be able to create accounts on our end. We don't want to work with a provider with a very strict KYC process. We want to be able to say, here's the EIN, here's the person's name, we know they have $X amount of money in their account, we know they've been in business for so long, just issue them a card.

From the anonymous founder of a neobank:

There's so little…. they can differentiate themselves on. Everyone is saying the same things: do you provide better ledgering? Dashboards? Better ancillary services? How much control do you let me have with the bank? Will you actually support me through the bank? Do you provide legal support? How do you handle disputes and resolutions? There are literally 200 to 300 things you need to consider.

I would say that maybe the top three things to look out for are, there's a lot of things. There's quite a few things, obviously capabilities. What do they offer from a platform perspective? What are their capabilities? Do they meet the different use cases? Do they provide API so the developers can integrate with those? So, from a platform capability is probably the number one. Another important one is availability and scalability, the ability to keep up and to keep the system up, even as programs grow to still be able to keep the system up is a big one. That affected Chime a few years ago, quite, quite, quite badly in that case. The other is how's their leadership? How's the leadership from an investor perspective?

One company from this group does stand out from the rest. Propelled by the success of customers like Square and Instacart, and with the advantage of an eight-year head start, Marqeta has simply achieved massive growth and far outpaced all of its potential BaaS or issuing competitors.

Marqeta’s headstart in the space has given them the ability to offer fintechs proven reliability at scale (from supporting Square’s Cash App), better economics, and a roadmap that can be flexible to the specific needs of the biggest enterprise customers.

The bigger players have a lot more leverage when it comes to business model scalability and technical scalability, for many reasons. One is they're usually better capitalized, so they can, at scale, give you a much better deal. They also probably have better partnerships and better cost models with their own suppliers. And, on the technical side, they have the benefits of just having been in markets for longer, and having supported larger players as well. You can see that they support the likes of Square. Square has scaled massively. And Marqeta is supporting them very successfully. So, if you're a small startup, I wouldn't worry about is Marqeta going to scale with me?

The upshot here is that Marqeta has scaled successfully to support the enterprise in a way that no BaaS provider has come close to replicating, and the advantages they reap at scale make it very hard to compete. But the enterprise-centric strategy that has brought Marqeta to $60B in transaction volume also leaves companies at the bottom end of the market, including startups, underserved. For BaaS companies, that means looking at a different kind of customer with a different set of needs.

3. Why BaaS companies are venture bets on the future of embedded finance

73% of Marqeta’s revenue came from Square in 2021, a fact which has earned its stock criticism on the basis of over-concentration. But the fact that Marqeta caught a ‘tiger by the tail’ in Square may reflect the reality of what it looks like to build a big API business.

Twilio was similarly criticized early on for its heavy amount of customer concentration. At the time of their 2016 10-K, two customers—Uber and WhatsApp—accounted for 20% of the year’s revenue. A further 10% of revenue came from a total of 8 other companies.

Twilio’ stock price has risen since then from about $50 to more than $300, even though the company lost Uber as a customer and continues to have a concentrated distribution of revenue, with 14% coming from 10 customers.

The reality is that for these kinds of companies, these concentrations reflect the basic power law dynamics of how a majority of companies fail or stagnate and a few standout companies break out and grow at fast rates.

BaaS businesses that want to build a successful business off developer-centric, self-serve APIs, as they put together a customer base, are also building a portfolio of venture-like ‘bets’ on those companies.

The quality of those bets will be a major driver of growth. If companies they’re partnered with break out, it can exponentially grow their transaction volume and revenue.

For BaaS, this means that embedded finance—made up by companies looking to embed cards or rewards or lending into their core product experience instead of fintechs that offer those things as the product itself—may be the opportunity they need to find that massive growth runway.

So far, the tendency has been that the economics of building for fintechs aligns well with going upmarket and building for the enterprise. A few breakout successes can almost be enough to build a strong business.

The limitation there is that fintech companies have such rigorous requirements that at scale, their BaaS providers can become beholden to their roadmap.

A company like Marqeta where 73% of their business comes from Square cannot build for the long tail of fintechs and companies that might embed some financial function into their product—though this opens up a corresponding opportunity for today’s BaaS companies.

The situation, as one senior BaaS executive described it to us: "Either you become a very high-end professional services company like Green Dot or Q2 or Synapse, or you try to basically do what Galileo and Unit and Productfy are doing, which is aggregate the long tail, all the hundreds of thousands of FinTechs, and basically try to monetize on the 10 to 20% of them that are going to start to grow up and become larger and larger and larger."

Because Marqeta is so firmly in the enterprise and isn’t going after the everyday fintech developer, it leaves open the long tail for the BaaS companies—and there are a magnitude more potential ‘embedded finance’ companies in that long tail than there are fintechs.

Similarly, Twilio didn’t necessarily pursue the most active companies already embracing some form of telephony as part of their core product. They went after companies like Uber— that needed to be sending texts every second as part of operating a car dispatch service, connecting drivers and riders. These were companies that wanted telephony as a means of enabling new kinds of product experiences.

Going after these kinds of ‘embedded telephony’ companies became Twilio’s main growth engine. Twilio’s customer growth did also remain majority-SMB even as they went public and disclosed those numbers that showed high customer concentration—because their long tail strategy was successful, and it was mainly a few breakout successes like Uber and WhatsApp that made their revenue look overly concentrated.

The future of banking-as-a-service

While there are questions about how the power dynamics between BaaS companies and their fintech partners may evolve, and about how repeal or modification of the Durbin amendment might change BaaS business models, one thing that appears certain is that the genie of BaaS isn’t going back into the bottle.

Banks, struggling to generate new sources of revenue amidst regulatory battles and digital transformation, have a new and fast-growing base of potential customers that need their charters.

BaaS companies are at the foundation of the most active time for fintech ever, fueling and capitalizing on their innovations in sectors old and new.

It’s possible that we will see a world where for banks, building and maintaining their channel to their BaaS partners is as common and obvious as building and maintaining local branches to retain customers was in the 20th century.