Pradeep Elankumaran, CEO of Farmstead, on the future of online grocery

Nan Wang

Nan Wang

Interview

Disclaimers: This transcript is for information purposes only and does not constitute advice of any type or trade recommendation and should not form the basis of any investment decision. Sacra accepts no liability for the transcript or for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies in respect of it. The views of the experts expressed in the transcript are those of the experts and they are not endorsed by, nor do they represent the opinion of Sacra. Sacra reserves all copyright, intellectual property rights in the transcript. Any modification, copying, displaying, distributing, transmitting, publishing, licensing, creating derivative works from, or selling any transcript is strictly prohibited.

Sacra: We’d love to chat about supply chain and cost optimization for the dark store operators. If we can start with some unit economics, I have seen gross margin between 20% to 30%...

Pradeep Elankumaran (“PE”): And what is the product mix here? Is it produce heavy?

Sacra: 60 to 70% fresh produce, the rest of it will be non-perishable groceries.

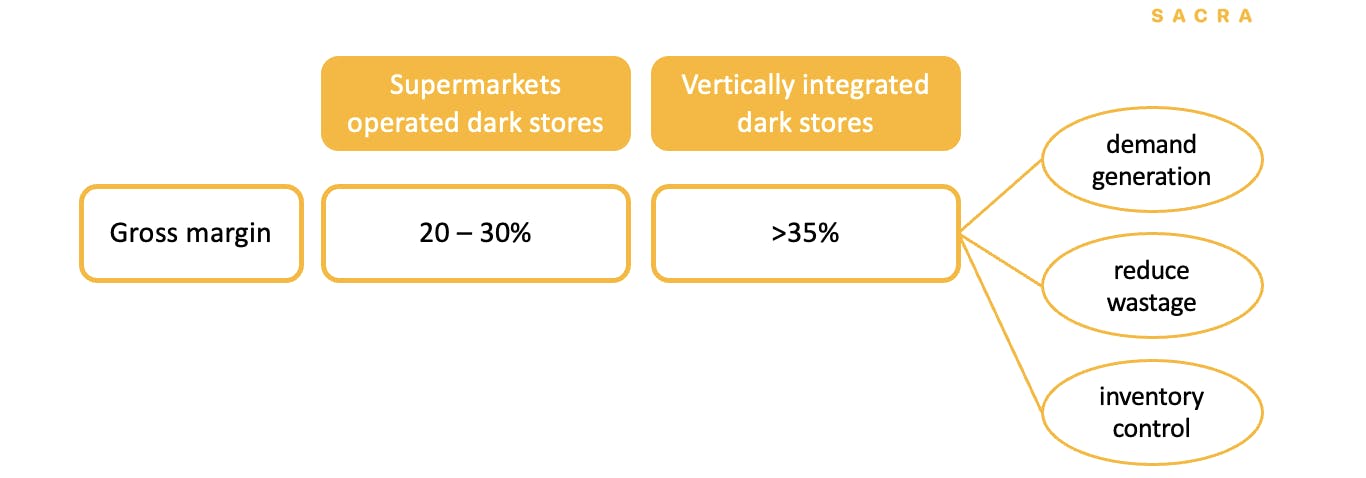

PE: I would say that's the margin mix that you see where a supermarket operator runs a dark store.

For vertically integrated dark locations starting from scratch, 20 to 30% gross margin is on the lower side.

Sacra: What's the range I can expect for these emerging players?

PE: Depends on how good they are at building demand. If they are especially great at it, and they’re able to sell the perishables without significant food waste and have strong inventory handling, then they can do north of 35% gross margins.

Sacra: In terms of spoilage, I have seen numbers between 2% to 10%. More traditional players, brick and mortar, are probably 10%+. Businesses that use intelligence and demand prediction can reduce the spoilage down to about 2%. How does that sound?

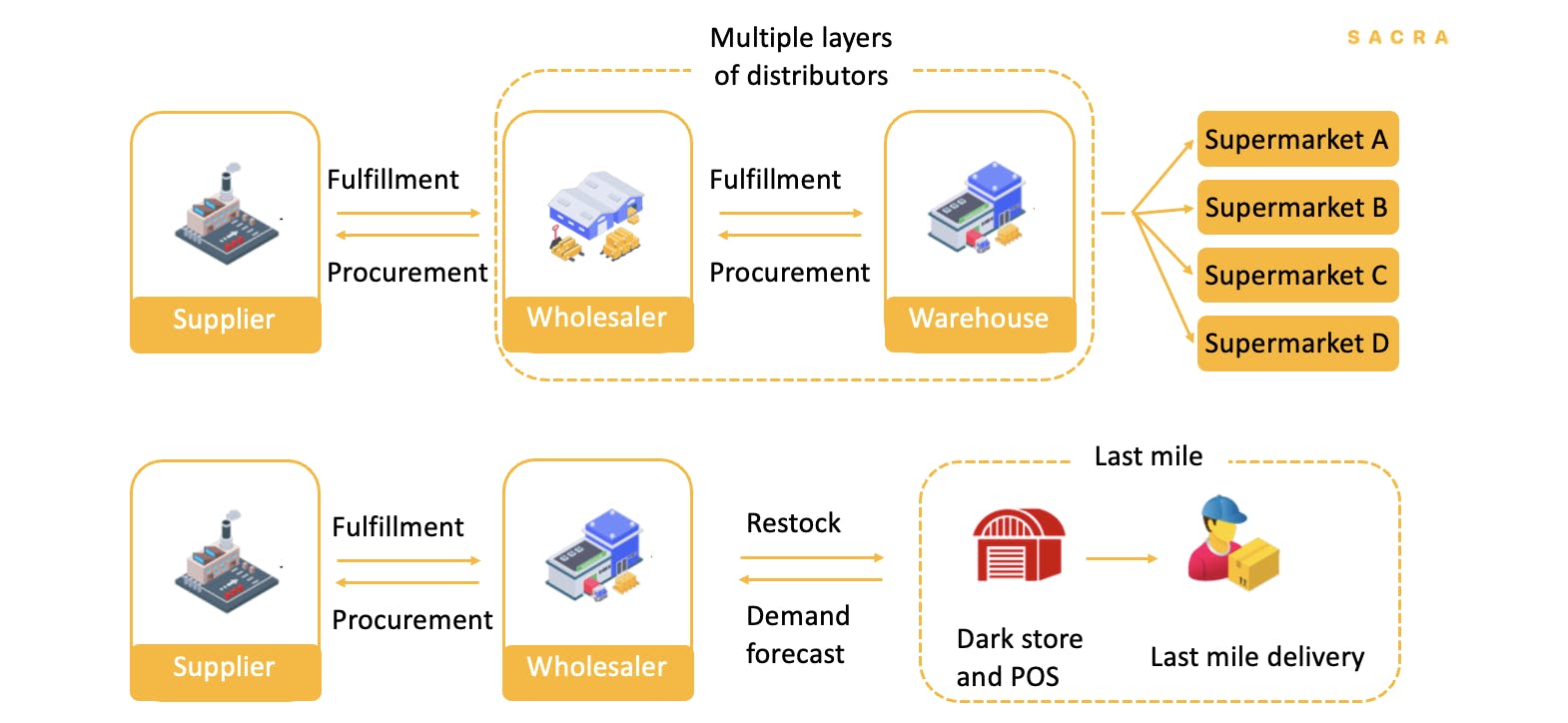

PE: It's all contextual. So it's not exactly just one fulfillment location we're talking about because there is usually a supply chain tied to any particular fulfillment center (whether that FC is a retail store or a warehouse), and the nature of that supply chain does matter.

If you are a supermarket, you are not just running a store, you're additionally running a distribution center that powers the store as well. So what is your actual food waste? Is it just what you're seeing at the store or is it actually what you're also wasting at the distribution center? Including the DCs, supermarkets tend to have double-digit food waste.

When you are moving away from the supermarket world and into standalone non-retail locations that suppliers deliver to -- i.e, the distribution centers plus point of sale that most vertically integrated grocers are running -- then you start seeing food waste drop to under 5%, especially with tech involved. At Farmstead, we are under 2.5% food waste in our best markets, and we accomplish this with our own code and our own data.

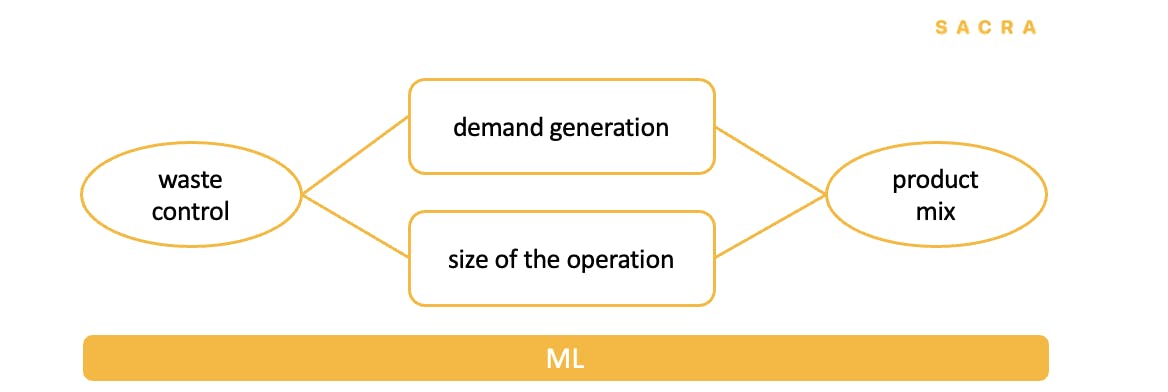

Food waste control is a function of demand generation and is also a function of the size of the operation. If you have a physically large operation, then you may be tempted to add more delivery volume to it, which leads to you buying larger volumes of products to sell, which you may wind up wasting.

Online grocery 1.0 like Webvan and Peapod failed because large warehouses were stocking large amounts of inventory, including perishables, and they didn't have the demand to back it up. Those operators were also assuming that they had to sell every single thing that a supermarket sells in order to maintain high baskets, which actually is not true. We have gotten over $80 baskets with just 1,500 products stocked, in contrast to a supermarket’s $100 basket with 30K products stocked.

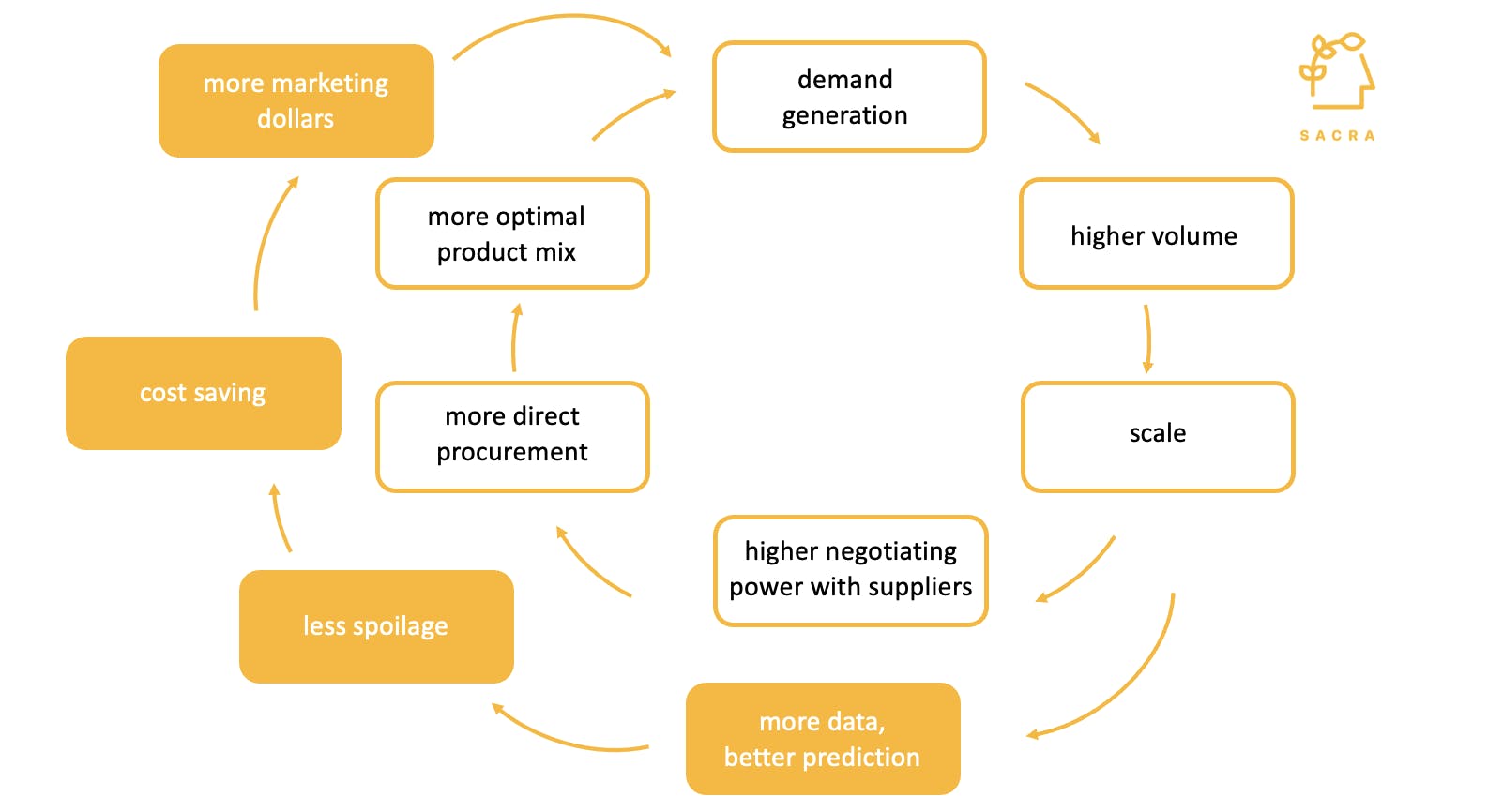

The product mix does matter a lot. If you're stocking primarily perishables and you don't have very fast inventory turns in your fresh department, then your food waste numbers will be high. But if you want to get the spoilage all the way down, then no amount of manual tweaking will get you there - you need very finely calibrated data powering custom-built ML models.

So our approach is to collect proprietary data. We get these from the tools that we code up for our own operations. The data we collect was spec'd out from scratch to be the right sanitized data that when combined with machine learning models allows for food waste reduction down to very low single digits, which improves our gross margins.

Sacra: When you say demand generation is it because when there's high demand, it increases the stock rotation, so there's less food waste because they all get sold?

PE: A better way of looking at it would be to inspect probabilities per item. So products like milk, the operator is almost guaranteed to sell any milk they stock because milk is more popular than basil. Milk also averages two to three weeks in expiry dates, enough time to sell the milk.

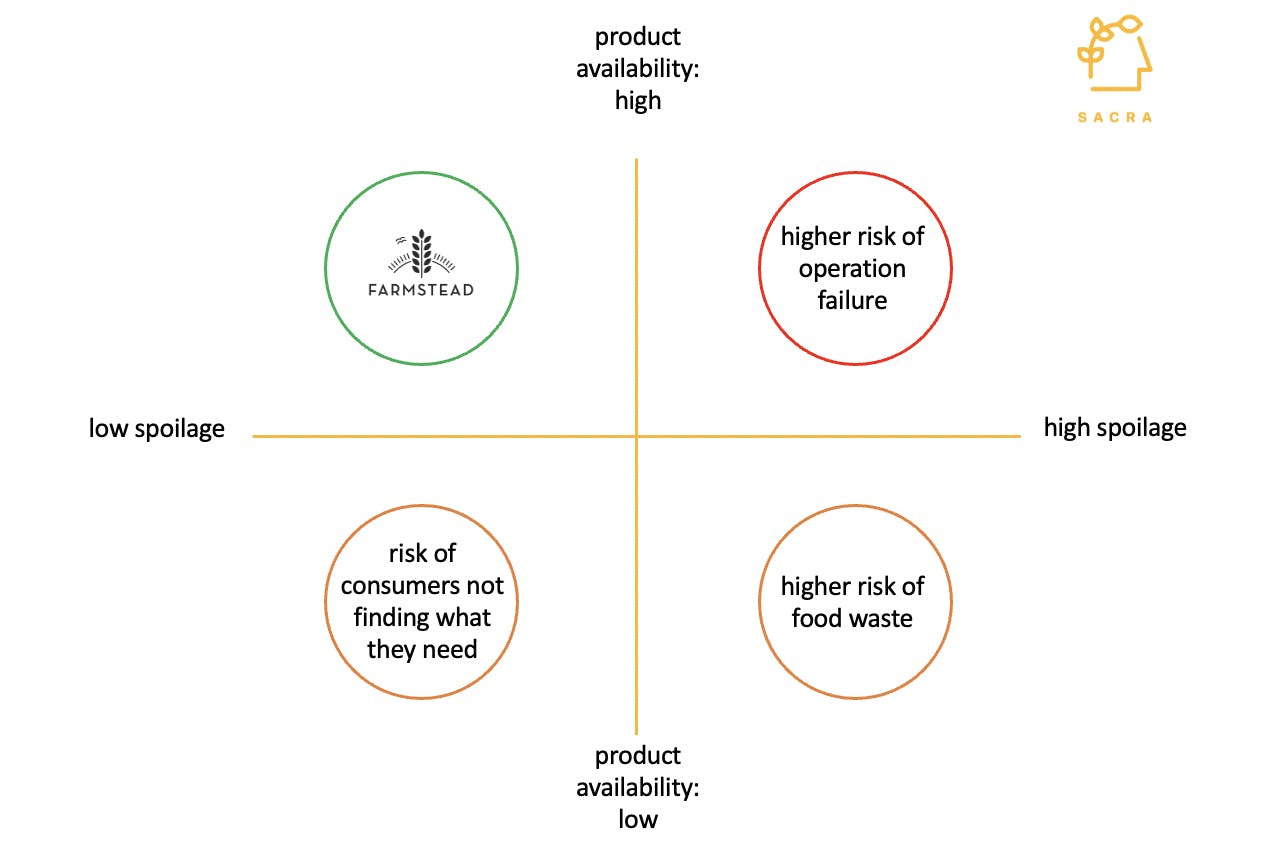

But if you're stocking fresh salmon, you really only have two or three days to sell the salmon once it hits your warehouse. So how much salmon should you buy? The answer contributes substantially to your food waste problem. If you buy too much, you run the risk of waste, if you buy too little then customers get upset and stop shopping with you.

So there are two prongs to trade off on -- product availability for customers versus food waste. It’s possible to get 0% food waste if you completely kill the product availability or buy exactly the same amount of products each week and subject the customers to out of stocks. Obviously, this is unacceptable.

So at Farmstead, when we say we have low food waste, that number is also coupled with very high product availability to customers. We predict on a per-item basis exactly how much to keep in stock so you can always find the product available as a customer, but also ensure that we have very low food waste using machine learning-led predictions. End result - sub 2% food waste.

Sacra: There are different ways companies can improve gross margin. Direct contract with suppliers is one. Could you help me to understand the cost evolution we can expect for dark store operators to have with suppliers?

PE: So when you first start a vertically integrated dark location, the goal is not to additionally run a separate distribution center that powers your own customer-facing fulfillment centers.

This is what supermarkets do. They're running a separate DC and that DC powers supply for multiple Safeway stores on the ground.

But when you're running a dark location, that location is both the DC and the consumer-facing point of sale, which gives you a big leg up with freight costs. So you're now looking to optimize your mix of suppliers instead based on their performance and wholesale rates. The suppliers’ trucks deliver directly to your warehouse, and you deliver the last mile to the customer.

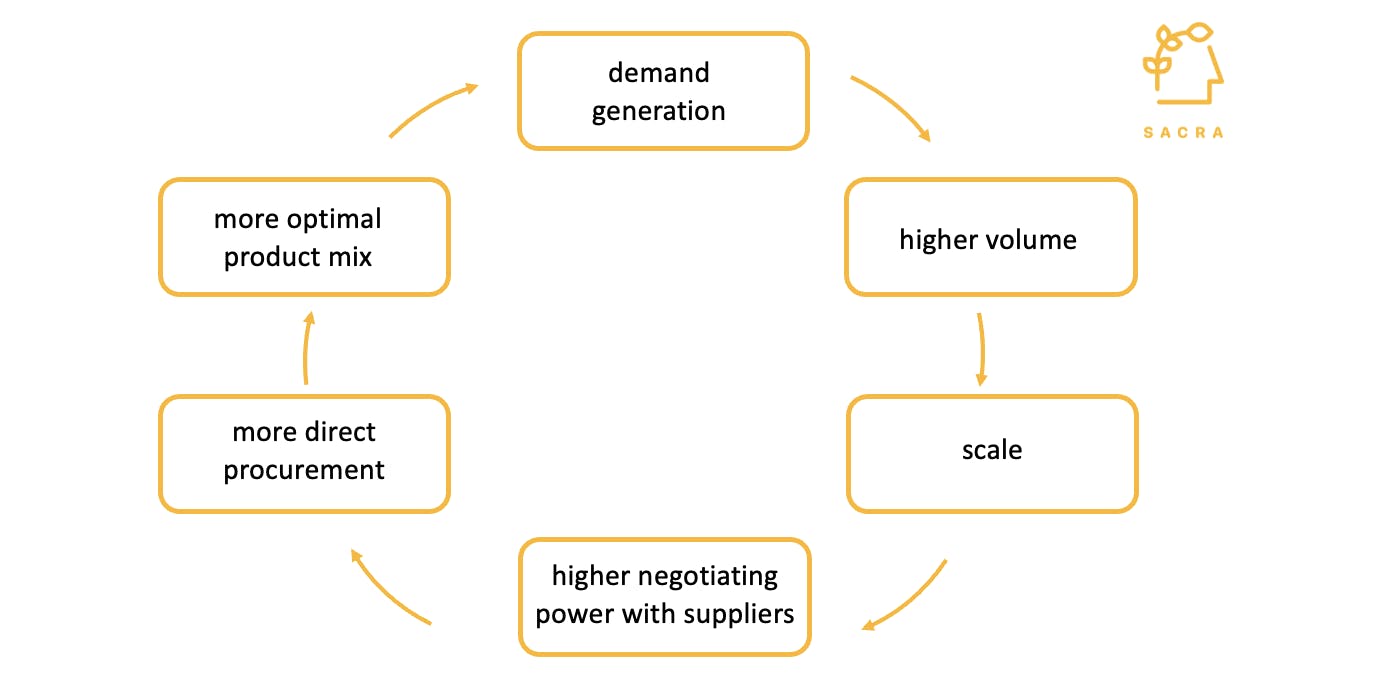

Now, the question of demand again matters. As you start your very first locations, you will only have access to the suppliers who service lower volume stores in your geographic area. As your demand increases, you start to get better rates because you're buying more supplies more often.

Note that your demand as a vertically integrated operator is usually higher than a traditional brick and mortar retail store because you're aggregating customers over such a big geographic radius. You're not talking about three to five miles like a supermarket’s delivery radius. You're talking about 10 times that, at a company like Farmstead.

The goal for a supplier is to fill a truck with stuff just for you before they send it to you. If they only send a quarter truck of products to you, then they're usually unhappy. If you have enough demand, then more trucks servicing your warehouse are filled primarily with products for you. This also improves your wholesale rates.

Next, especially with produce, you can start predicting exactly what you're going to sell and informing your supplier, who can then work with their own supply chain to predict better and get better rates. As the prediction ripples all the way down to the producer of the product, you start seeing significant cost savings. The price you're paying for broccoli is really tied to the waste levels of the distribution all the way up the chain to the farm until it gets to you.

When you're large enough, you always have the option of sidestepping all of those interim points in the supply chain. You’re now bringing enough demand that you can go directly to the producer of the broccoli and do a direct deal or directly to Nabisco for Ritz crackers - your economics improve substantially. You can also then start doing direct marketing relationships on the CPG side to layer on more margin.

Sacra: Let’s talk about the cost of distribution. For example, if there are three tiers of distributor between the supplier and the dark store, how would you think about mark-up on the product?

PE: A good way of thinking about it is that every step in the supply chain in between the producer of the product and the final point of sale to consumers would want to take their 20% cut.

With perishables, it gets pretty interesting. If you as an operator can get food waste down to very low single digits, then you can start stocking more perishables without fear, which is what customers want -- “fresh and local” is really the new organic. When you're stocking primarily perishables, you actually wind up with substantially better gross margins when you're selling primarily non-perishables. This is a disproportionate result relative to supermarkets, which do 20-28% gross margin. Perishable-focused dark locations can easily do 33%+.

There are a lot of new companies out there now like GoPuff who are doing primarily non-perishable delivery out of dark stores. Non-perishables are interesting for this type of model because you can start off at pretty low gross margins with low food waste. As the demand starts building, then all of your trade dollars start showing up for marketing, and then you're starting to make more margin just on the marketing while directly working with CPG companies.

However, the challenge with the primarily non-perishable model is that customers across the board want more fresh products than non-perishables, so getting the systems right to control food waste does matter for long-term rapid growth and retention.

Sacra: Online grocery is a thin gross margin business and delivery costs are inflexible. What are the key profitability levers?

PE: For new operators, it’s really building demand, getting your tech right and you're soon able to start pushing on gross margin. However, gross margin is only a small part of the story. If you really want to post significant gains on the bottom line, many other variables matter deeply.

Basket size matters. Even if you do increase gross margin, with a $20 basket, you will not be able to sustain your operations. You will not get to break-even per order.

The cost of delivery per order is usually somewhere between $5 and $15, depending on how good your operations are. The cost of labor per order, between $5 to $15 in most parts of the United States.

So you need to make more gross margin than the cost of labor and the cost of the driver summed up, while keeping daily order volume high enough that your labor costs amortize towards the low single digits like any standard e-commerce operation.

Now I would argue that “thin margins” is a very software-driven way of thinking. Software has 80% to 90% margins, so it's not fair to compare software to selling bananas. We're talking about two very different industries, and the lower margins are offset by the scale.

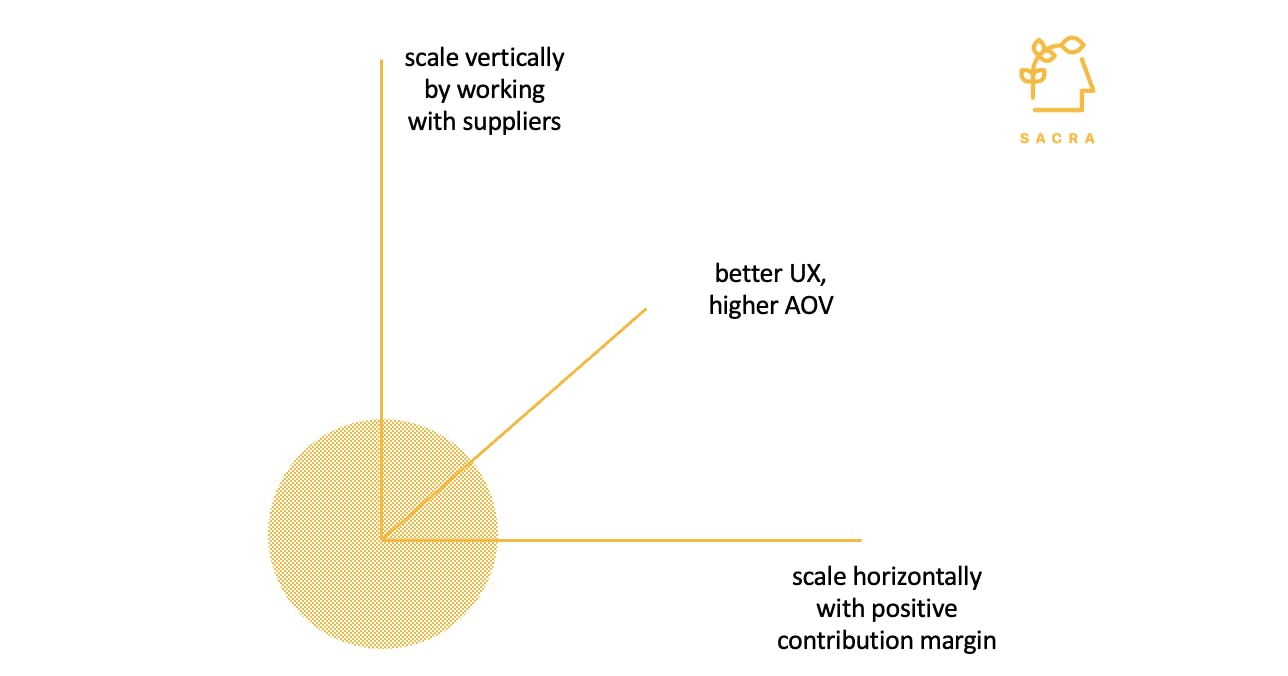

With tech-driven, vertically integrated warehouses instead of stores powering delivery, it’s possible to aggregate more scale efficiently in fewer locations and across broader radii compared to supermarkets.

At Farmstead, we are unconvinced that it’s possible to make profits per order with baskets under $50 in the United States (with its high labor costs relative to international markets) even if your gross margins are in the 30%'s.

The ways operators typically increase baskets are to increase prices or to increase order minimums -- both tactics artificially suppress demand and reduce the probability you will have a high number of orders per day, which you will need to reduce the cost of labor and delivery.

The number to look at versus gross margin is actually contribution margin, which is the basket minus all of the variable costs -- the gross margin assisted COGS, the cost of picking/packing, the cost of the delivery and finally the cost of packaging and marketing.

When your basket is higher than $50 while also selling products at the same prices customers pay at the store, customers are referring their friends/family, your gross margin is in the 30%s and labor and driver costs are trending towards single-digit dollars per order, then you can make positive contribution margin per order. Then you can take that extra positive contribution margin and pump it back into marketing and make each market grow even faster.

This new reality is very different from the old one with supermarkets clearing 2-3% net profit. The new reality connects demand directly using digital channels instead of opening a store and waiting for someone to show up. You’re also able to work directly with producers to get better gross margins. You're now able to use personalization and a better customer experience to increase the basket size consistently. You’re able to use technology-powered operations to scale nationally.

You can do thousands of orders per day in a well-run, tech-enabled warehouse with tens of thousands of square feet. The challenge is: can you get enough digital orders connected to that warehouse?

The holy grail of online grocery is thousands of online orders per day, out of horizontally and vertically scalable warehouse facilities, with a positive contribution margin and gross margins in the thirties.

When an operator can do that, and are able to attract customers at the prices they are already paying and low or no fees, then that operator is a valid contender to take over a decent chunk of the grocery industry in the US.

Sacra: In addition to density and demography, what other factors do you consider when you pick new locations to expand?

PE: Growth rate of the population, the total addressable population and the actual effective time to drive from the warehouse to wherever most of your customers are going to be.

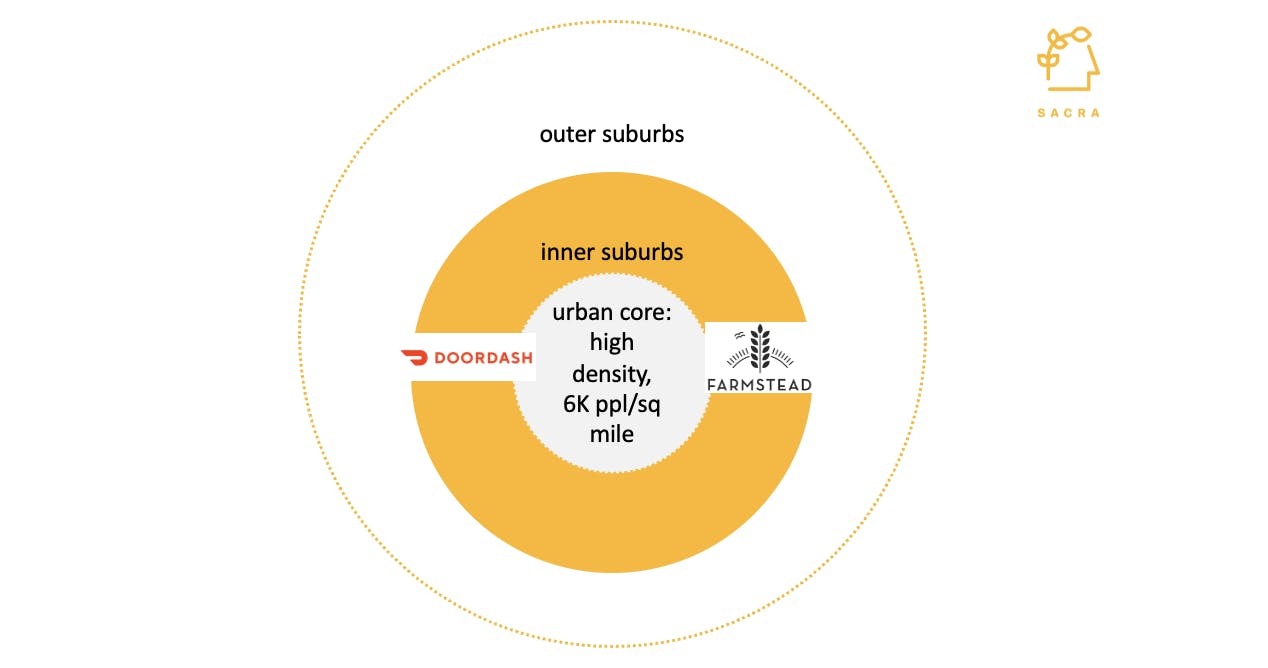

Density is a very complex variable. The way we think about density in each market is that there’s typically an urban core (in the Bay Area, for example - San Francisco city), outside of which are the inner suburbs, outside of which are the outer suburbs.

So historically cities have been very, very high-density urban core areas, you're talking about 6K people per square mile, but our inner suburbs are actually pretty dense too, usually 3,000 to 4,000 people per square mile minimum.

Inner suburbs are historically not well understood in delivery with the bulk of the invested dollars in ridesharing and delivery historically going to urban-core focused companies. DoorDash was the first company to really pin this down and understand that there's actually substantial density here in the inner suburbs, and is usually populated with households who love delivery and are considered ‘mass-market’ for grocery in general.

We prioritize marketing in inner suburbs first, then urban cores, then outer suburbs. Since we run our own delivery, our goal is to increase the number of stops delivered per hour substantially. Our drivers usually deliver 4-5 stops per hour, versus the 1.5 stops/hour market average, even while delivering to a 50-mile radius, with a 2-hour delivery window at the edges of that radius.

So with a high population growth rate over the last five to seven years, the markets we choose are young growing markets, with a higher population of folks who have a higher probability of saying yes to delivery. If you're the kind of person whose first purchase on your credit card was textbooks off Amazon, then you probably want to buy things online instead of buying things at a store, and we want you as an online grocery customer in these markets.

Sacra: Do you see any first-mover advantage in securing prime real estate?

PE: No. You can sneak these locations into new markets in non-warehouse areas, including light industrial zones and existing unused retail spaces while trading off on delivery capacity per day.

National footprint matters a lot more than a specific real estate location at a particular cross-street. If you are able to reach more customers in more markets than anyone else, and you're able to spin up these locations up inexpensively, digital marketing results favor you.

So then the questions become: how small can a warehouse be and still do thousands of orders per day, how fast can we spin them up and how inexpensively can we launch them?

At Farmstead, we spin up a new location within 14 days with less than 100K invested on day one. We can get these things to a breakeven point within six to eight months while meeting all the variable thresholds we discussed before - gross margins, low cost of delivery, low cost of labor, high baskets.

Sacra: Do you see partnerships and M&As as a more efficient way to scale?

PE: Supply is one of the more interesting pieces of online grocery at the moment. The act of layering additional brands on a distribution facility of any kind, whether it's a store or a warehouse is not very well done at the moment. This is a huge area of opportunity. For example, all the 50,000 supermarkets in the United States, at any point in time, are supply depots that can connect to customers.

But no one has really figured out the unit economics of that in compelling ways like Instacart didn't do a good job. Neither did Shipt, nor did Cornershop, but there is a way to get those economics right - it may be you start grouping all the demand that's now tied to stores into bigger warehouses.

You don't need a lot of automation in a dark location, by the way. Automation with expensive picking robots is not necessary to do most of the things that we just talked about. You can do it with just manual work and the warehouse-led distribution industry has been doing it manually for a very long time.

What I think technology can really bring to the table right now is demand generation. Making demand actually click into a location is a lot harder than you might think. Stores have marketing baked in, but warehouses don’t. Digital advertising channels are complex enough that it takes years to master. The existing players don't have a real good sense for that. The new folks, especially if they have a technology background, have a significant advantage in doing so.

Partnerships matter for larger grocers now more than ever. Amazon and Walmart are applying pressure and entering the mass-market grocery world. Customers have gotten a taste for delivery during the COVID period and found out that they actually like it. The challenge for all operators is to drive increasing digital adoption, but doing this is very challenging. We’ve recently started with work with them, offering up our backend stack Grocery OS as a way to combat these threats.

The promise of e-commerce has never been fulfilled for grocery -- customers pay the same or lower prices as stores, get free delivery and a perfect order every time.