Anduril, SpaceX, and the American dynamism GTM playbook

Jan-Erik Asplund

Jan-Erik Asplund

TL;DR: Product-centric defense tech companies are flipping the traditional military procurement model based on cost-plus contracts, self-funding their R&D and setting their own prices, getting to 50% margins vs. the 10% of a Lockheed Martin. For more, check out our interview with Scott Sanders, Chief Growth Officer at RRAI and 7th employee at Anduril, and our report and dataset on Anduril.

Key points from our report:

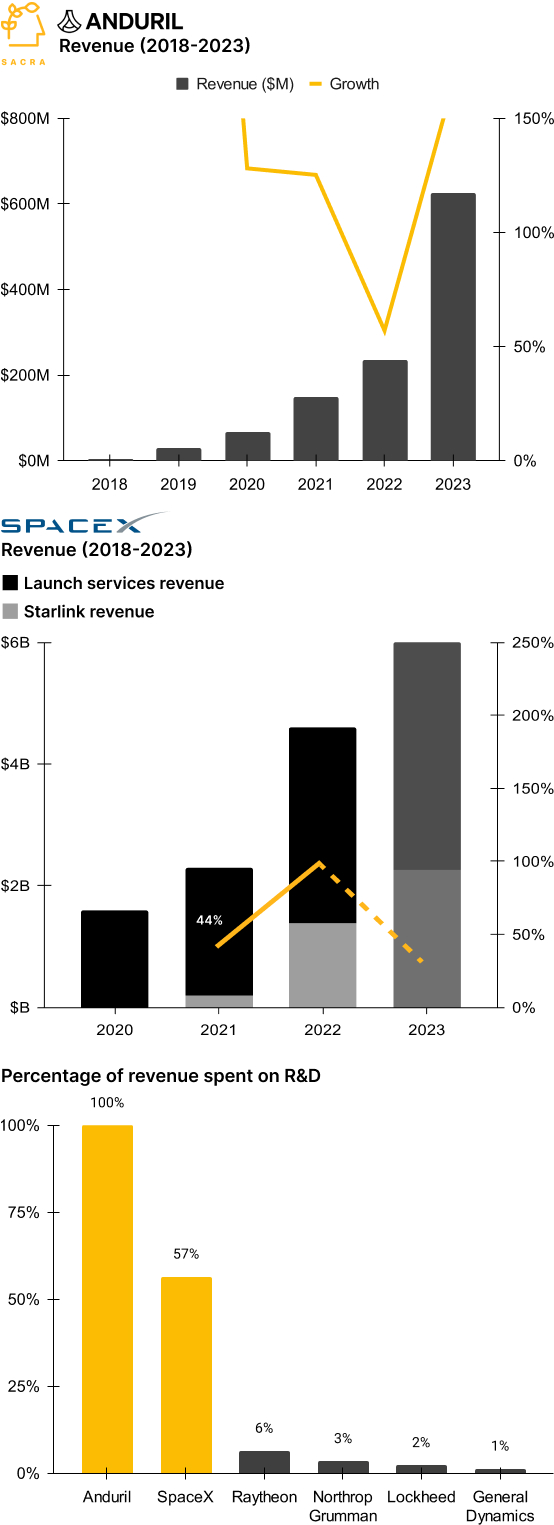

- In World War 2, as conventional armies faced off in large-scale ground battles, the government enlisted hundreds of American private sector contractors to build the tanks, planes, and boats—see Lockheed’s (NYSE: LMT) P-38 Lightning fighter and Electric Boat’s (NYSE: GD) USS Gato and Balao-class submarines—that were key to the Allied victory. Between 1937 and 1955, Lockheed grew from 2,000 employees to more than 100,000—sales grew from $3M in 1935 ($150K profit) to $35M in 1939 ($3.1M profit) to $732M in 1955 ($22M profit) and their profit margin hovered around 8-9%.

- As the Cold War shifted the focus of America’s arsenal of democracy, strategic strike capacity and nuclear deterrence replaced large-scale mobilization via innovations like General Dynamics’ (NYSE: GD) SM-65 Atlas intercontinental ballistic missile and Northrop Grunman’s (NYSE: NOC) F-14 Tomcat. The decline in defense spending post-WW2 led many contractors to pivot to commercial to survive, but many didn’t make it—between 1960 and 1972, even Lockheed made just $255M in profit on $26B of revenue for <1% profit margin.

- The Cold War wound down in the 90’s and Department of Defense (DoD) spending fell by 55%, triggering a massive wave of consolidations that created modern defense giants like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, decreasing competition, and increasing the use of cost-plus contracts. The share of DoD dollars awarded noncompetitively—via projects with only a single bidder—grew by roughly 18% as 70% of all defense companies folded or were consolidated.

- Cost-plus contracts—where the government covers all of a contractor’s costs and pays ~7-9% profits on top—mobilized American companies to build tanks and bombs for WW2, but they came under increasing criticism in the 2000s as insufficient for delivering the tech and software necessary to fight asymmetrical, guerilla wars against non-state actors. In the 20th-century, cost-plus contracts incentivized defense contractors to keep investing in headcount and facilities and maximize our domestic production capacity, but winning these new kinds of wars and keeping soldiers safe increasingly hinges on rapid delivery of data and technological superiority, not munitions.

- SpaceX (2002), the first startup to go after cost-plus contracts, sold fixed-price launches to NASA at 10% of the cost of Boeing (NYSE: BA) by using vertical integration to build drastically cheaper rockets. NASA first made the jump from cost-plus to fixed-price contracts for an ISS resupply mission in 2008, when friend-of-Elon Mike Griffin—who had seen the first successful launch of SpaceX’s Falcon 1—was the head of the agency.

- In military intelligence, Lockheed Martin's habit of building software from scratch collided with Palantir’s (2003) insurgent hybrid model which sells software consulting alongside productized SaaS, driving bottoms-up adoption by winning with battlefield commanders on the ground. To close their first Army contract, Palantir had to file a lawsuit to first force the Army to do their legal duty and consider commercial products when procuring new platforms—an ultimately successful legal maneuver that cleared the way for companies like Anduril and RRAI.

- Anduril ($600M+ revenue in 2023) similarly self-fund their own R&D—spending 100%+ of revenue on R&D vs. ~2% for Lockheed—using miniaturized GPUs developed for the gaming industry to build border sensors and autonomy systems fast and at a fraction of the cost of prime defense contractors, allowing them to win on a lower fixed price. Boeing’s Secure Border Initiative Network project, started in 2006, ultimately ended up covering just 53 miles of the United States’ 1954-mile southern border at a cost of $1B—in 2020, Anduril signed a deal with the government to cover the entire border for just $250M.

- Where Lockheed rode cost-plus contracts to build a $65B/year factory for American armaments with perma-10% margins, product-oriented companies like Anduril, Palantir, and RRAI use their 50%+ gross margins to underbid and win contracts, pour their revenue into R&D, and then ship more and better products into multiple markets. By selling into multiple markets like the military, local transit, and logistics, companies like RRAI benefit from the overall upside of autonomy while avoiding the downside risk of a vertical-specific slowdown, as we’re seeing in freight with Convoy’s shutdown.

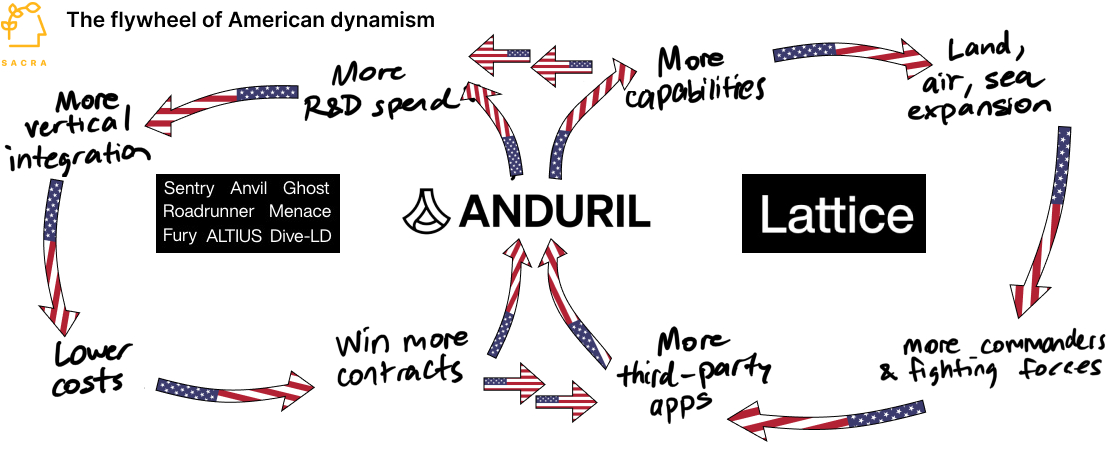

- It’s a rare land grab moment in defense tech, with companies like Anduril using their DoD sales motions and relationships with commanders to create moats to entry and then opening up access for third parties to sell apps through their platform, ala SpaceX with Starlink. Similarly, Salesforce (NYSE: CRM) parlayed their proprietary relationships within the enterprise to build AppExchange ($26B in partner revenue as of 2022), enabling other companies to sell into those relationships without doing direct sales themselves.

For more, check out this other research from our platform: