WeWork: How the $3.5B Flex Space Giant is Engineering A Comeback

Nan Wang

Nan Wang

This report contains forward-looking statements regarding the companies reviewed as part of this report that are based on beliefs and assumptions and on information currently available to us during the preparation of this report. In some cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by the following words: “will,” “expect,” “would,” “intend,” “believe,” or other comparable terminology. Forward-looking statements in this document include, but are not limited to, statements about future financial performance, business plans, market opportunities and beliefs and company objectives for future operations. These statements involve risks, uncertainties, assumptions and other factors that may cause actual results or performance to be materially different. We cannot assure you that any forward-looking statements contained in this report will prove to be accurate. These forward-looking statements speak only as of the date hereof. We disclaim any obligation to update these forward-looking statements.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Join our list for more of our exclusive private markets research and company coverage.

Success!

Something went wrong...

WeWork is inarguably one of the most controversial companies in the world. Its unsustainable growth strategy destroyed billions in shareholder value. Has WeWork finally hit rock bottom, or is it a falling knife?

We don’t have a crystal ball, but based on the work we have done, we believe WeWork has most of the pieces in place for a powerful turnaround.

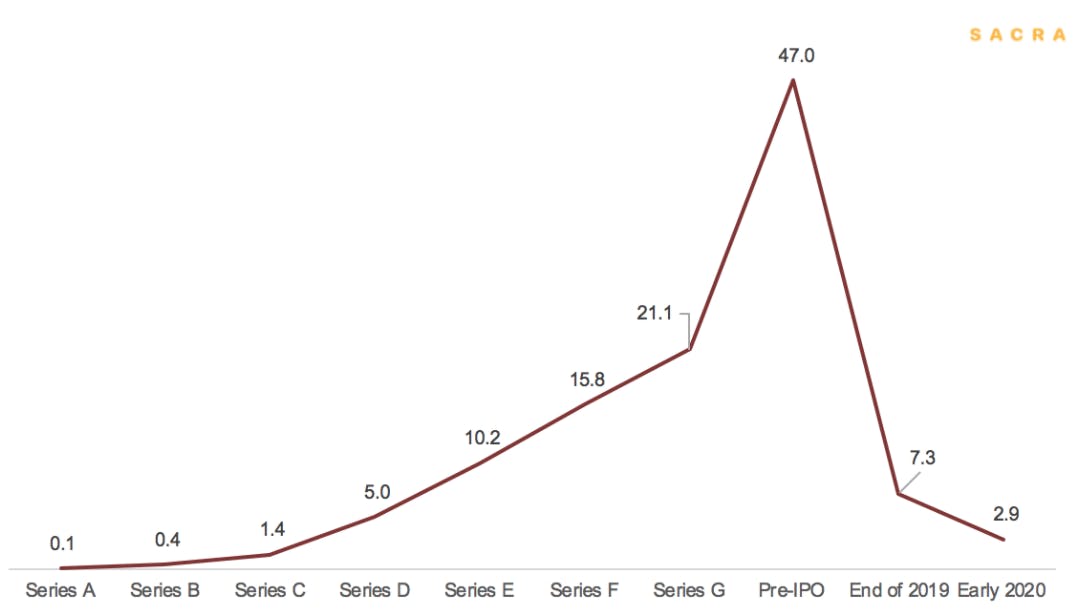

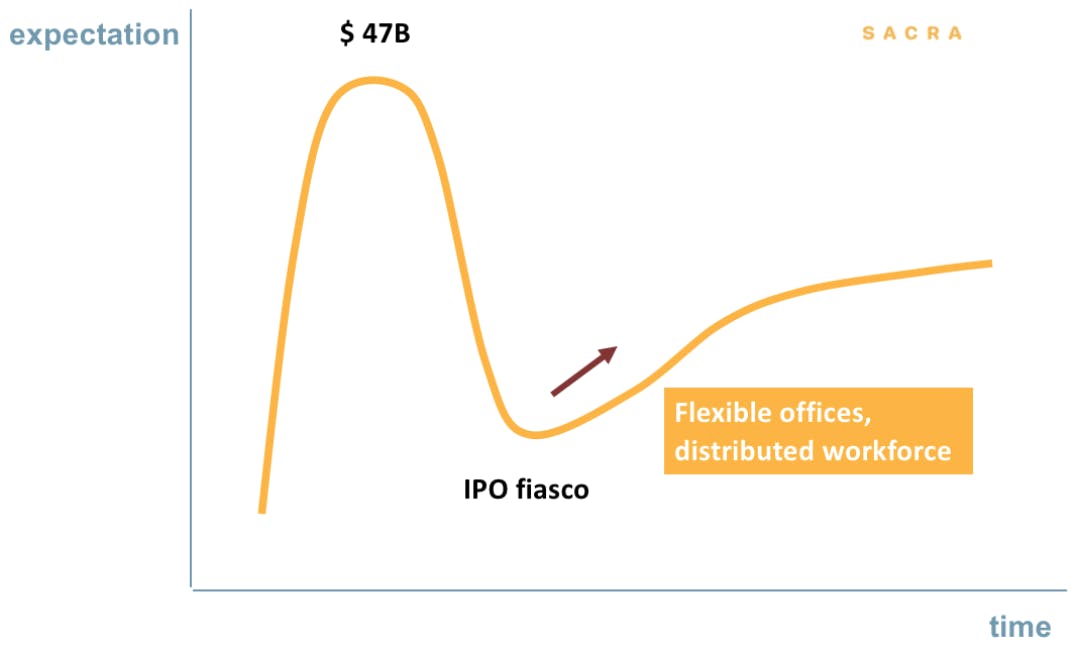

In January 2019, WeWork was valued at $47B, making it the second-largest private company at the time, 15x the price of its closest competitor. After its failed IPO at the end of 2019, it nosedived to $7.3B. In March 2020, just as offices around the world were closing amid the coronavirus outbreak, SoftBank refused to participate in a $3B tender offer of early employee shares. The valuation of WeWork fell all the way to $2.9B, down 94% from its peak.

WeWork’s rise from startup to $47B company took 9 years—its fall back down to $2.9B took just over 1.

The private markets have gone from euphoria to disillusion with WeWork. The company was downgraded again by credit rating agency Fitch in October 2020, and its cash burn through the year so far is estimated to be above $1.6B.

Our research shows that after all the recent changes, there is a light at the end of the tunnel. We aggregated public data, analyzed financial data, talked to real estate brokers, developers, industry experts and built a model.

We can scoff at WeWork’s one-page long community adjusted EBITDA, but the company has been undergoing a reorganization towards profitability.

Key decisions include rightsizing their real estate portfolio, exiting 66 unprofitable leases, effecting a favorable shift in customer mix shift with 60% revenue now coming from enterprises, reducing the size of the workforce from 14,000 to 5,000 and hiring a new management team.

In addition to WeWork’s internal efforts, the most unexpected tailwind is that the global experiment of remote working that we’ve seen during COVID may give rise to a structurally more flexible and distributed workforce in the near future. Ironically, the economic downturn many thought would sink WeWork may become the very cause of its survival.

A capital light strategy is also on the horizon (a genuine one this time). Once the dust settles, WeWork could leverage its existing business and office management services and transform itself into a franchise provider.

WeWork’s road to redemption

- Our DCF model gives WeWork a valuation of $3.5B. At this price, WeWork equity resembles a call option, with limited downside but asymmetric upside.

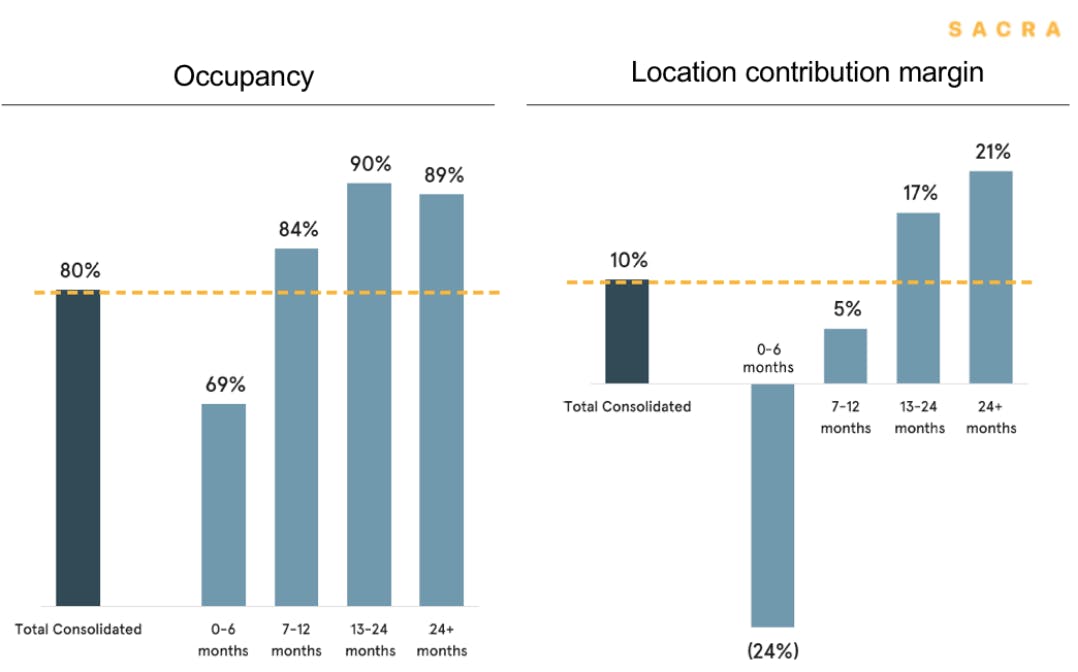

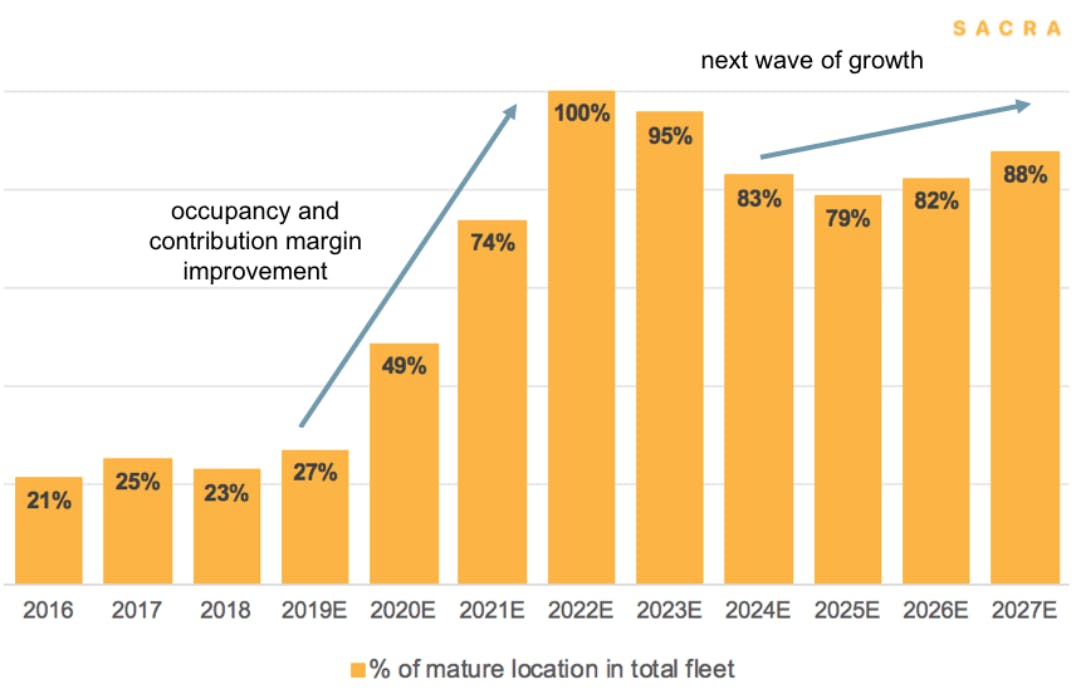

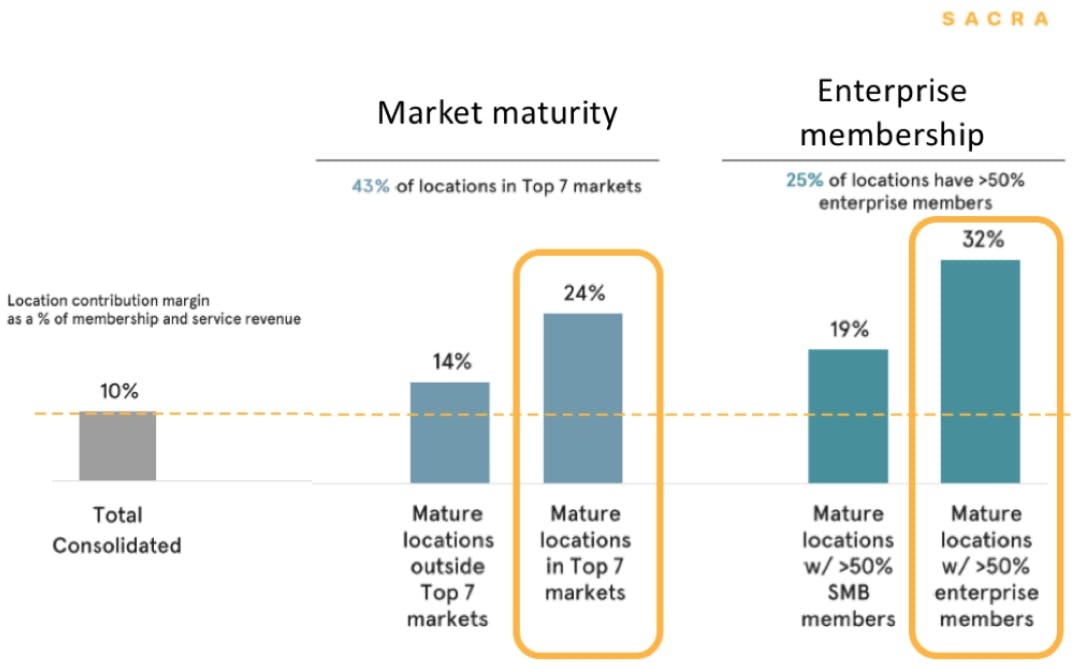

- The site economics behind WeWork's core business are surprisingly positive. 24 months after opening, the average WeWork location can generate a 20% contribution margin, compared with economics from more stable peers. A big reason for WeWork’s cash burn was its lack of mature locations. In 2019, WeWork had the biggest flexible workspace footprint, but the lowest % of mature sites, comparing with its profit-making peers.

- WeWork has become much more prudent in new location openings. Mature locations are expected to grow to 50% by the end of 2020 and reach 100% in 2022.

- WeWork has spent 2020 stabilizing its core operations with 4 key measures.

- 60% of WeWork's customers are now enterprises. During the pandemic, WeWork leased 3.5 million square feet to enterprise clients, including TikTok, Mastercard, Microsoft, Citigroup and Deloitte.

- WeWork's new CEO is a real estate veteran. The current CEO is a disciplined operator with successful turnaround experience.

- WeWork has rightsized its real estate portfolio. We estimate WeWork has exited 66 locations and amended about 150 leases, driving higher average occupancy and margins across their portfolio.

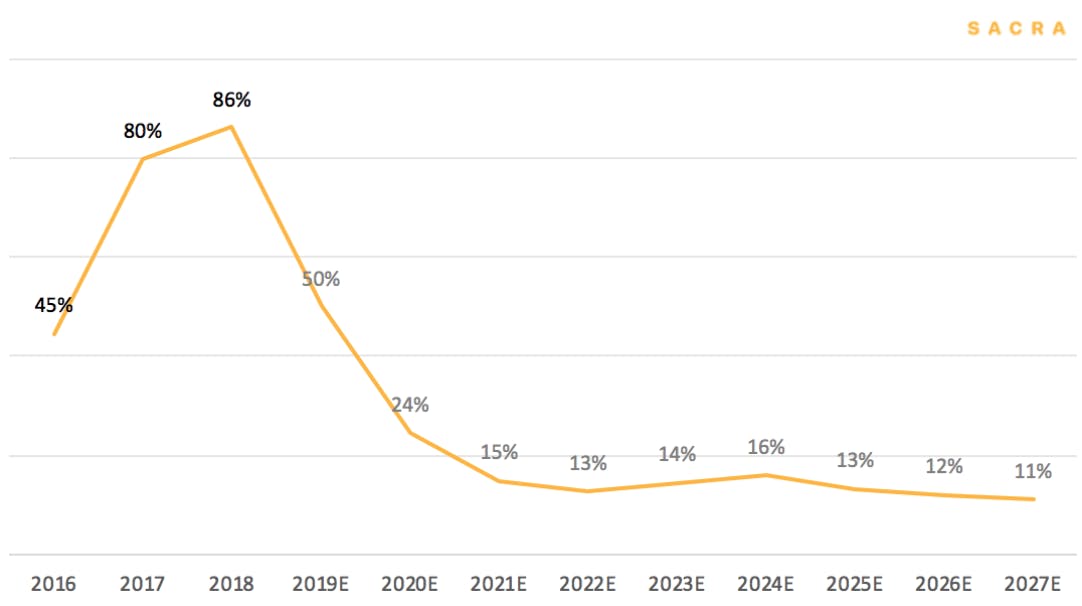

- WeWork has cut costs. WeWork has shrunk its workforce by 60% and cut many experimental growth projects, such as WeLive, WeGrow and self-driving chairs. Operating expenses are trending down significantly, from 86% of revenue in 2018 to an estimated 50% in 2019.

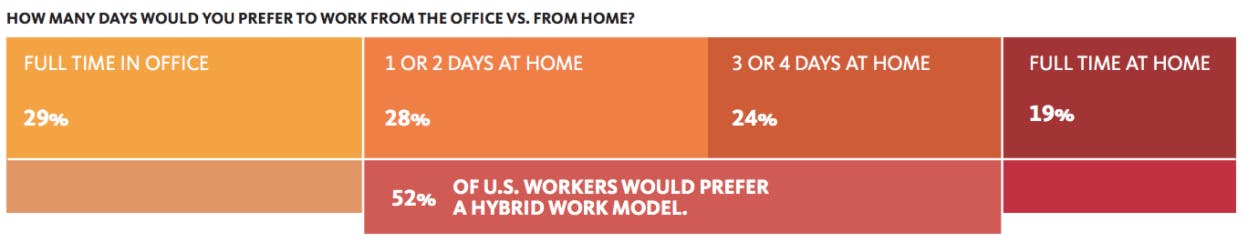

- Market dynamics are changing. Post-COVID, 80% of people want to return to the office a few days a week but keep the benefit of flexibility. Ironically, the downturn many thought would sink WeWork may become the very cause of its survival.

- WeWork is quietly transitioning to an integrated, tech-enabled ecosystem coordinator. Despite the large cost cutting, WeWork continues to invest in community services, aka, the "killer app". For example, WeWork Labs is a community digital platform. It provides cross sector incubator services to support companies to acquire skills, meet peers and experts.

- If WeWork can leverage its physical locations and build a tech-enabled layer on top, it could reshape the real estate stack with itself as a middleware to connect people and optimize spaces.

Valuation: WeWork is worth $3.5B

WeWork Financials, DCF, and Dataset

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

WeWork Financials, DCF, and Dataset

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

Our base case discounted cash flow (“DCF”) model implies a 2021 forward equity value of $3.5B for WeWork.

WeWork still has the shape of a distressed company. The capital structure is heavily indebted and equity is at the bottom of the pecking order. Nevertheless, the equity resembles the asymmetric risk/reward profile of an out of the money call option.

In other words, given the current financial and operating dynamics of the company, for every one unit of enterprise value increase, the upside is amplified for the equity holders.

For anyone to stand behind WeWork now, however, they must be comfortable with a lot of macro uncertainties related to GDP, unemployment, speed of returning to the office and the opportunities around what the future of workspace would look like.

If WeWork can stabilize their operations in the near term through delayed capital spending, improved occupancy and regained focus, there could be a meaningful upside.

We highlight the structure of our model below.

Our aim with our model is to capture WeWork’s key growth and cost drivers to have a sense of the company’s profit-making potential. We used company disclosures from 2019 and turnaround guidance to form the base case assumptions. Our model calculates enterprise value by subtracting net debt and capitalized operating leases to derive equity value.

We can summarize our DCF into three distinct phases:

- Phase 1: 2020 - 2024 turnaround and stabilization.

- Phase 2: 2025 - 2030 disciplined growth in the core business, expansion in franchise model and other business services.

- Phase 3: 2031+ steady-state growth at 2%, with the overall occupancy to remain at 90%.

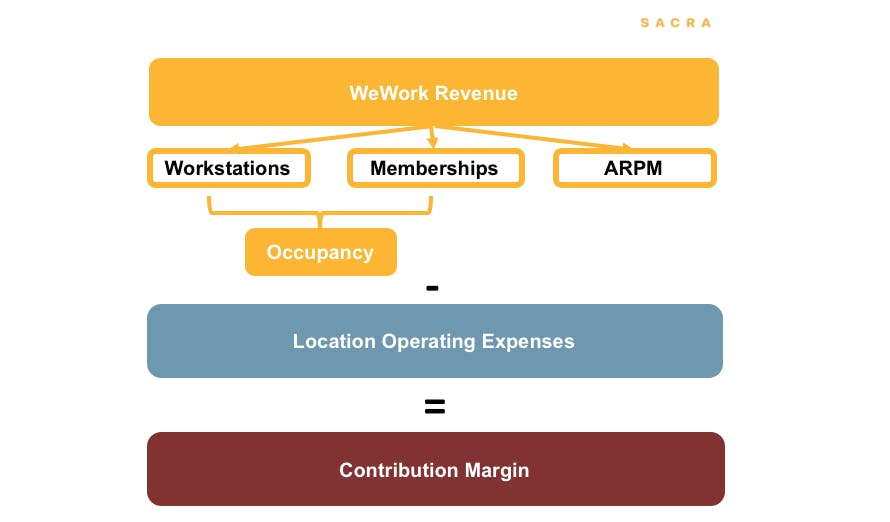

We disaggregate revenue into total workstations, total memberships and average revenue per member (“ARPM”) to derive occupancy rates. We also build a CapEx profile based on cost per workstation to calculate location level contribution margin (WeWork defines contribution margin as membership revenue minus location operating expenses before headquarter administrative costs, growth expenses, marketing and stock-based compensation).

WeWork's revenue drivers.

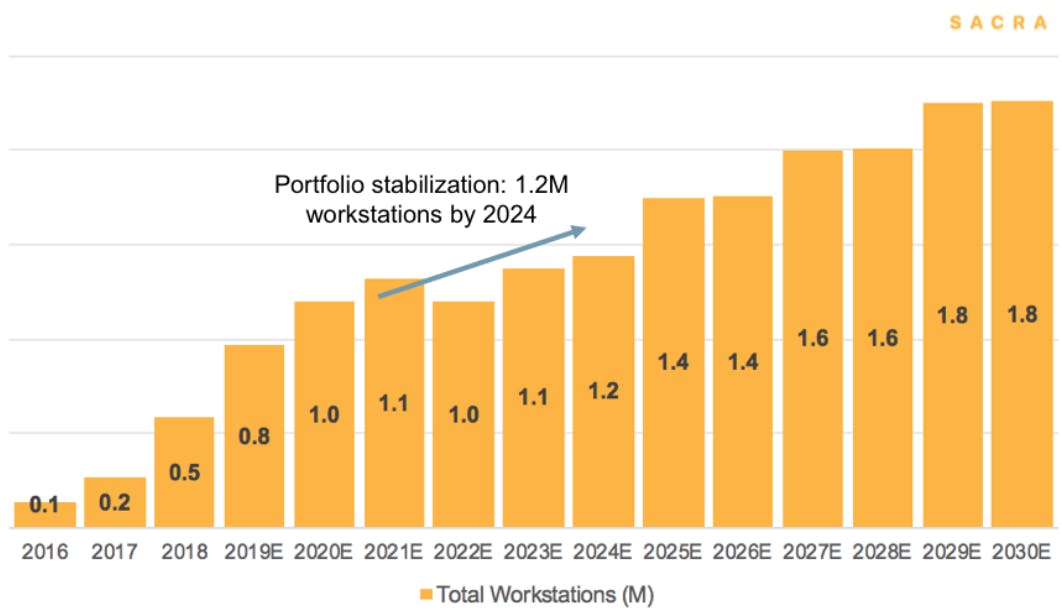

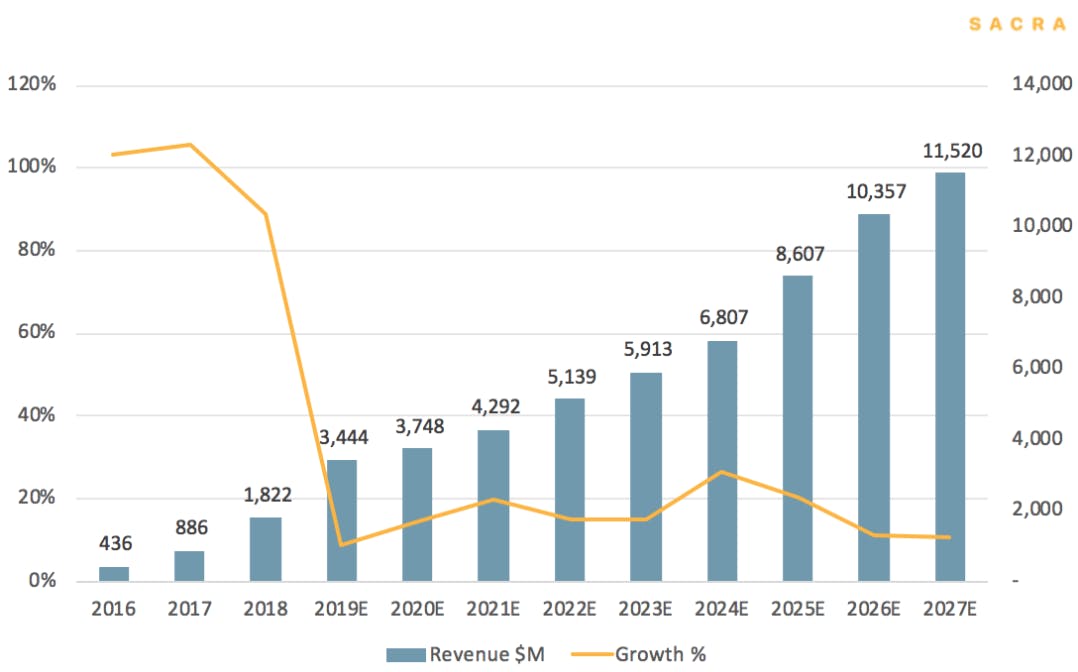

WeWork doubled its total workstations between 2016 and 2019. As a result, mature locations accounted for only c.30% of the overall portfolio. To preserve cash and streamline operations, the pace of expansion has slowed significantly. The base case assumes total workstations to grow at 5% p.a. to reach 1.2M by 2024.

We illustrate our key revenue and cost assumptions below.

Post the initial phase of “growth at all cost” prior to 2019, we model that between 2021 and 2024, WeWork would become more selective in new location openings, as well as, more prudent in the number of new openings.

Revenue: We model a slower revenue growth rate before WeWork achieves profitability.

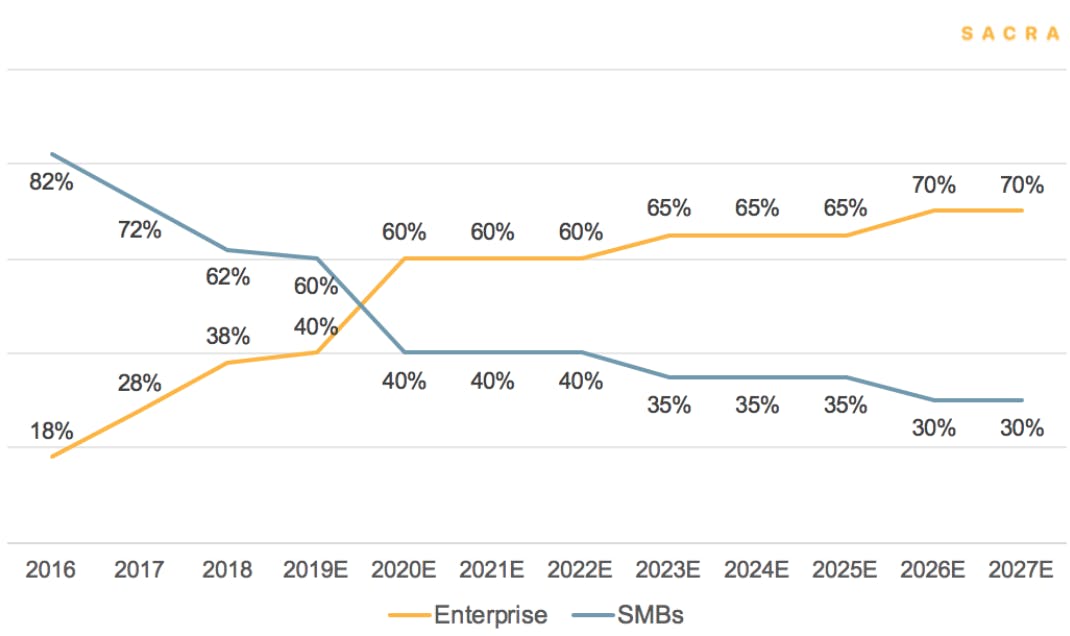

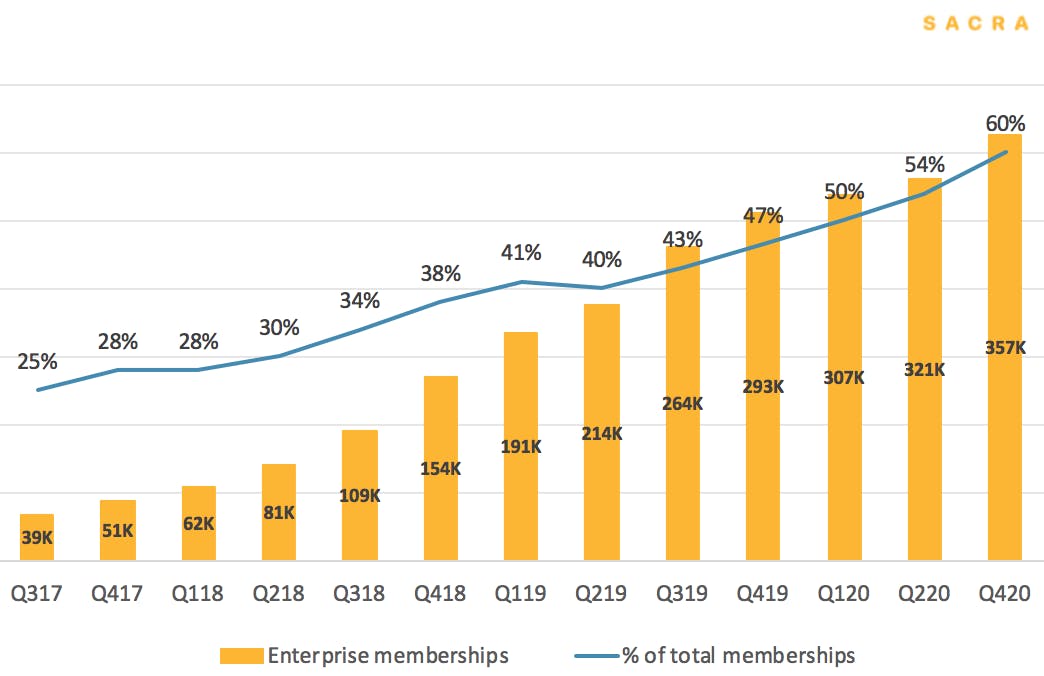

Mixed shift: Enterprise memberships contribute 60% of the revenue in 2020. It is a positive trend that it almost doubled since 2017.

We model that, post the company-wide cost-cutting, operating expenses will reduce to a similar level as IWG.

As a large portion of the portfolio becomes mature, occupancy improves and so does the contribution margin. The company strives to achieve a contribution margin of 30% in the long term (WeWork S1, Page 73). Our base case assumes the contribution margin to reach 18% in 2024, then gradually trending up to 30% by 2030.

A detailed DCF model and sensitivity analysis are available in the appendix.

Business model: From capital-heavy to capital-light

WeWork Scenario Analysis, Risks, and Funding History

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

WeWork Scenario Analysis, Risks, and Funding History

Members

Unlock NowUnlock this report and others for just $50/month

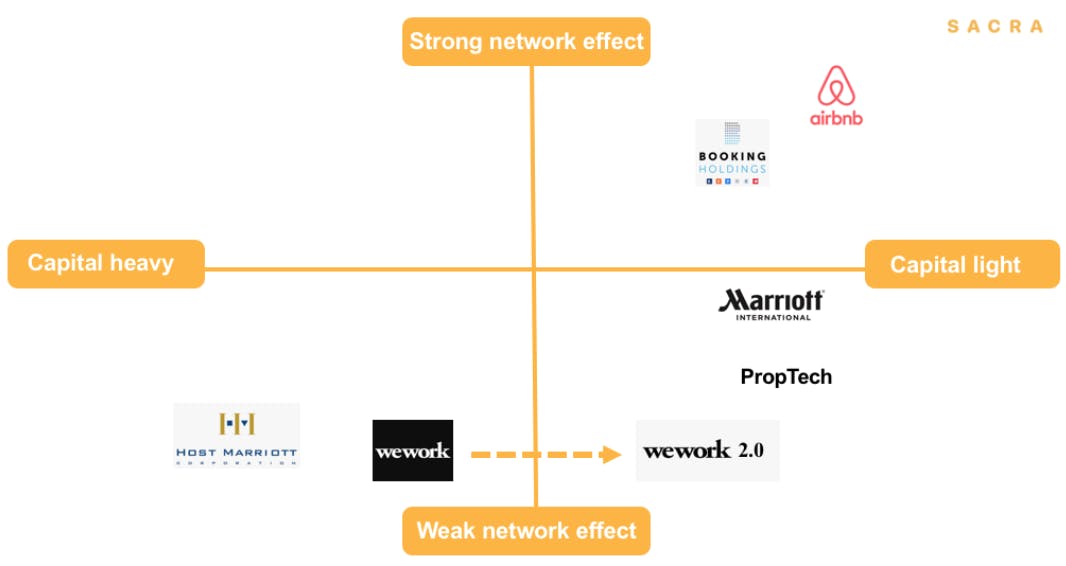

WeWork is a real estate company. There are three aspects to WeWork’s business, moving from capital heavy to capital-light.

1. Subleasing: a middleman between landlords and tenants

WeWork buys wholesale and sells retail. It signs longer-term leases with landlords, generally 10 to 15 years, then subleases them at a higher price per square foot on more flexible terms. Individuals can rent a desk or private office, and businesses can rent office suites or an entire floor.

The main criticism of WeWork’s business model is that it creates a duration mismatch. A duration mismatch occurs due to WeWork’s long-term liabilities (leases) and short-term assets (rents). This exposes landlords to counterparty risks and burdens WeWork’s balance sheet with heavy lease liabilities. This is a valid concern and cuts to the heart of WeWork’s raison d’étre.

2. “All Access”: office on demand

All Access is WeWork’s first response to a more flexible workplace. It is an on-demand membership that provides access to hundreds of locations globally at $299 per month. All access is gaining traction as WeWork sold over 100,000 of these memberships in September 2020.

This is a near-term operational lifeboat to improve the company’s contribution margin. The economic benefit of All Access is that for the same amount of fixtures and space, a higher flow of people could generate more revenue per desk.

Unlike independent and small flexible office providers, WeWork has site density to provide convenient locations. For example, 96% of office workers in Manhattan (and more than 58% of those in New York City) live within a 15-minute bike ride or are within walking distance from a WeWork location.

3. Franchising: capital-light makeover

WeWork is diversifying its monetization channels. Since May 2020, WeWork has been developing its franchise model to provide management services for landlords. This franchise model, exemplified by companies like Starbucks and Marriott, is attractive because it is capital-light and growth can accrue without too much incremental cost.

There is a market for this. IWG has already transitioned to a franchise model. The largest Chinese flexible office provider Ucommune also manages 221,400 m2 under the franchise model, representing 40% of its total spaces. Ucommune sees this approach as one of its major growth drivers.

Hotel businesses and commercial real estate businesses have some core similarities.

Hotel owners can make low double-digit annualized returns over 30-40 years. This is an even more attractive proposition in the current low-yield environment. Let’s take Marriott’s business as an example. Marriott is a brand owner, who partners with third-party hotel owners. The hotel owners bear most of the capital investment to build the property. They fit out the space according to Marriott’s specifications. Marriott, the brand owner, manages distribution, marketing and supplier negotiations. When travellers stay and pay for the room, a part of this income will be paid by the hotel owners to Marriott as royalties for the distribution and other services.

Since August 2020, despite the deceleration in revenue per available room, all the major hotel brands continued to sign new hotels to their pipelines.

If owner returns in hotels can be indicative of flexible workspace returns, then, WeWork’s franchise business could provide attractive returns to property owners.

Analysis: How WeWork’s turnaround could be the perfect fit for a post-COVID world

1. The surprisingly positive site economics behind WeWork’s core business

The problem with WeWork was not its buy wholesale sell retail site economics, but rather its exponential increase in costs and hyped valuation. The media was purely fixated on the growing losses reported by the company. However, these losses were driven by rapid global expansion. Purely looking at WeWork’s site-level economics, it can be a viable operation.

In October 2019, management guided that for an average site, the contribution margin was 10% at 80% occupancy. The margin would increase as occupancy improves. At a mature site, defined as 24 months post-opening, the contribution margin surpasses 20%.

The contribution margin improves as locations mature.

Source: Company filings.

The contribution margin is a crucial data point. How can we substantiate this in absence of WeWork’s disclosure on location financials by vintage year? To find further evidence, we looked at other flexible workspace providers, who are more stable and mature versions of WeWork.

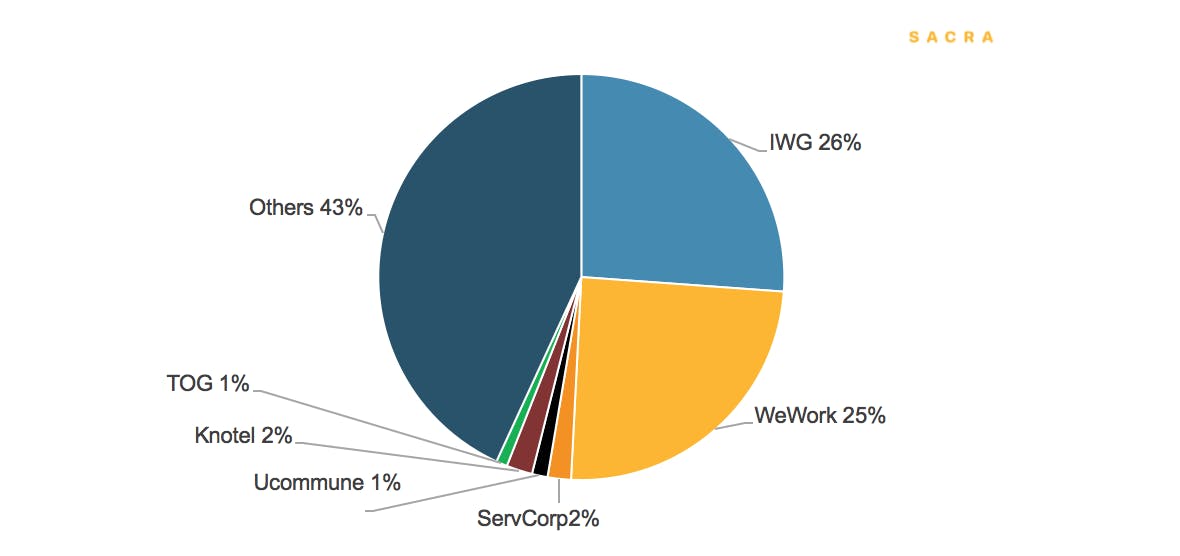

The flexible workspace market is fragmented. It consists of a handful of global players and a large number of local and subscale operators. The top two players have 51% of the market and the top six players have 57% of the market share.

WeWork is a top provider and has a quarter of the market share in revenue terms, and a third of the market share in footprints.

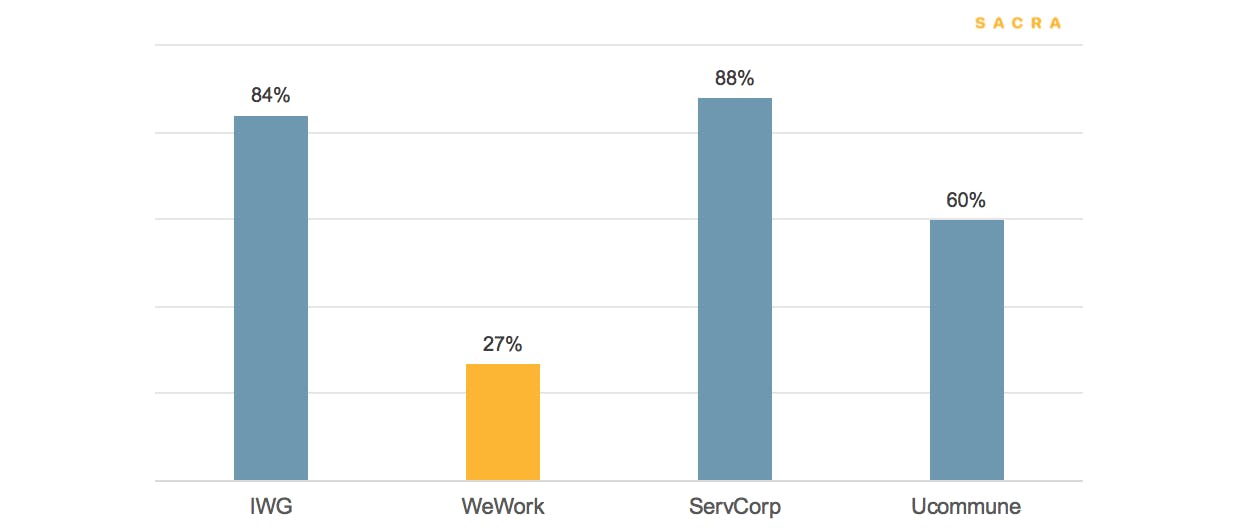

Servcorp and IWG are two profit-making and cash-generating global providers.

- Servcorp has been in operation for over four decades. Fundamentally, it operates under the same model as WeWork’s subleasing real estate business. Servcorp has an 8-15% operating margin and 8% return on capital.

- IWG reports a 6-10% operating margin and 12-16% return on capital. IWG has an umbrella of six different brands, which include the more conservative Regus, as well as, the more vibrant and entrepreneurial brand Spaces. Spaces is a close peer of WeWork. However, IWG does not disclose each division separately.

The margin and return profile from industry peers suggest that WeWork’s guided contribution margin is plausible. The upper and lower bounds of ServCorp and IWG’s operating margin range between 6% and 15%. Assuming a steady-state operating expense of 15%, this leads to a 20 - 30% contribution margin. In other words, WeWork’s losses and cash burn are largely results of undisciplined capital allocation, instead of uneconomical fundamentals.

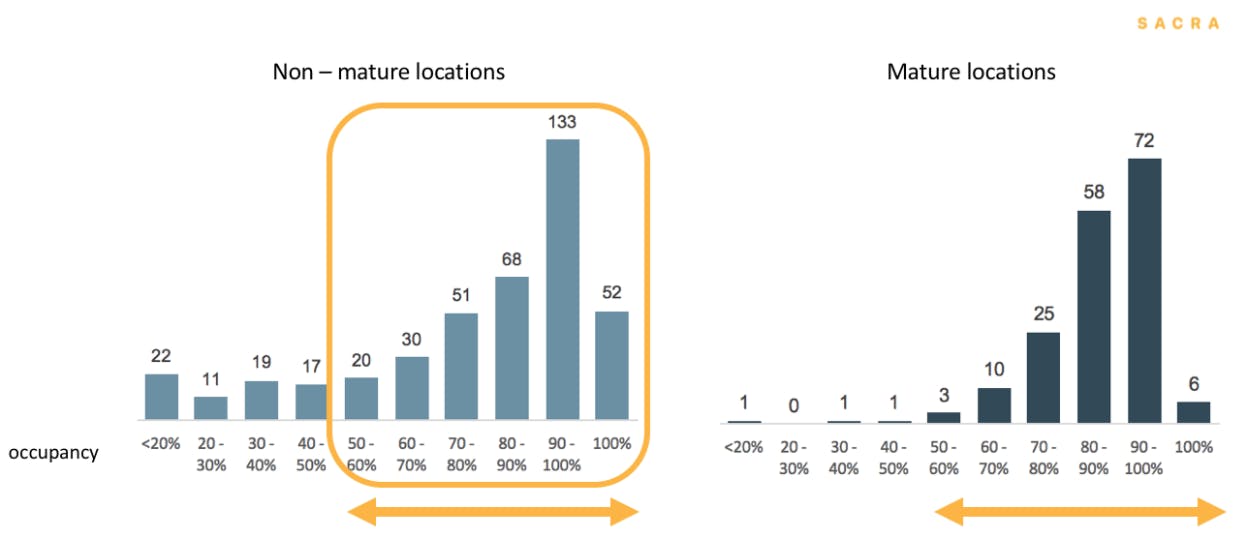

Indeed, for the profit-generating providers, such as IWG and ServCorp, more than 80% of their locations are mature. In contrast, only 30% of WeWork’s operating sites reached maturity in 2019, which meant that 70% of the sites were still in the ramping up phase. This was a big reason behind the headline cash burn.

Only 30% of WeWork’s operating sites were mature in 2019. WeWork is pausing location expansion to improve profitability.

The revised growth plan aims at a mid-single-digit unit growth, as opposed to the previous high double-digit growth. This would vastly reduce near-term CapEx requirements. Hence, we estimate that the mature locations will increase from 30% of the portfolio to 74% by 2021 and reach 100% in 2022, before the next phase of investments.

Mature locations are expected to grow to 50% by the end of 2020 and reach 100% in 2022 before resuming the next wave of more disciplined growth.

The positive site economics set a foundation for scaling the business and future growth. Just like Starbucks, once the single site economics makes sense, the operation can be replicated across different cities to boost profitability. As a result, better locations drive higher traffic, higher unit economics allow it to compete more effectively.

2. How WeWork’s failed IPO forced the business to recreate itself

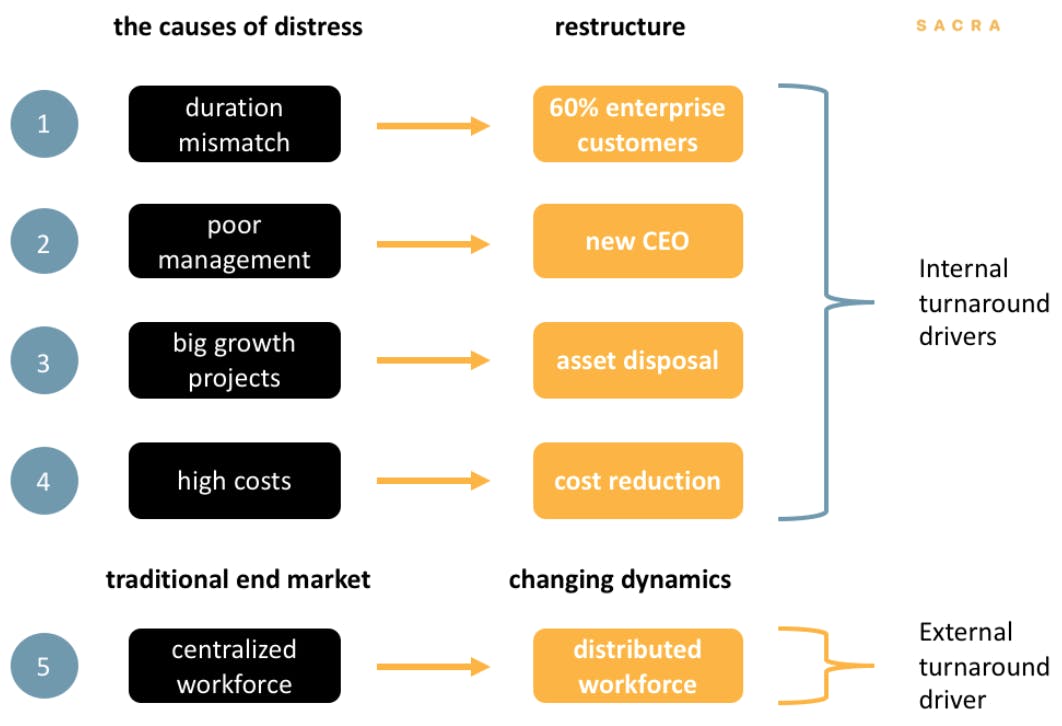

WeWork was a rising star, then it imploded. A chain of inter-related causes triggered the rapid decline. Duration mismatch, poor corporate governance, over-expansion and excessive spending crippled the IPO.

It has been over a year since the beginning of the turnaround and free beer is not the only thing that the company has eliminated. WeWork has spent 2020 stabilizing its core operations, improving management capabilities, optimizing real estate footprints and cutting costs.

In addition to these four internal remedies, there is an unexpected external factor joining the mix. The global experiment of remote working may provide structurally higher demand for flexible workspaces in the near future.

WeWork's turnaround drivers.

Turnaround driver 1: Mix shift to more enterprise customers

To mitigate the weakness in its business model, WeWork has been expanding its enterprise customer base (> 500 employees) from 18% in 2016 to 54% in Q320. These contracts are typically 2 -5 years with discounts based on commitment levels.

As a % of total memberships, the enterprise segment has grown from 25% in 2017 to 60% in 2020, more than doubled in 4 years.

This mix shift is a positive trend for two reasons.

Firstly, from the landlords’ perspective, it is important to have certainty on a tenant’s covenant strength and profitability, because the landlords want certainty on when and how they will get paid from the tenant.

Through our primary research, we learned that there were cases when WeWork pre-empted upcoming demand from fast-growing technology companies to open buildings in certain cities. However, some landlords would reject WeWork’s offer and far prefer to lease directly to the corporates.

With a high degree of duration mismatch, WeWork has been an unpopular tenant for landlords. As a result, WeWork had to pay higher prices to secure buildings. However, real estate developers we spoke to also acknowledged that having a higher portion of enterprise customers would be a step towards the right direction for WeWork to improve its stability.

Secondly, growth in enterprise has contributed to higher desk sales and longer commitment lengths.

During the pandemic, Bloomberg reported that average WeWork occupancy dropped from 85% to 66%. This was in line with the wider office real estate market and dampened the assertion that WeWork was a fundamentally unsustainable business.

A higher mix of enterprise customers protects the degree of the drop because these tenants have longer leases and are bound by contracts. Our primary research with industry experts indicated that near 100% of enterprise customers honored their payments, c.50% of SMBs canceled their contracts during COVID.

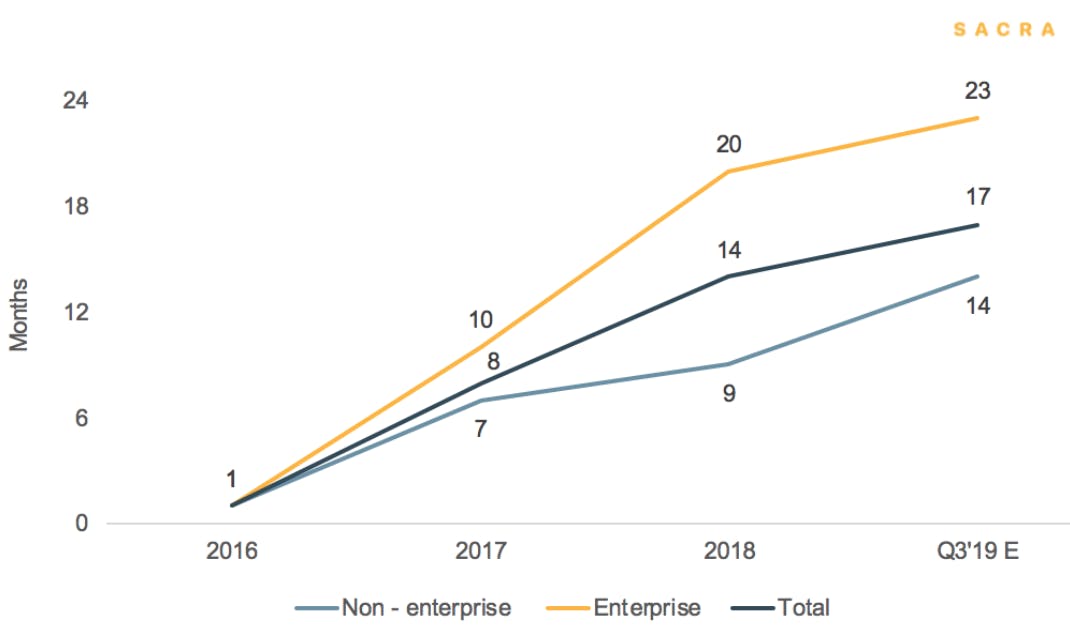

Enterprise memberships have an average commitment length of 23 months. The increase in enterprise memberships has also improved the total average new commitment length to 17 months.

We have spoken with tenant representative brokers who work with WeWork. The brokers highlighted nuances in office leasing, which could differ building by building and case by case. However, they also acknowledged that WeWork could become more compelling for enterprise customers post COVID, given its geographical diversity and breadth of availability. This can save time because instead of negotiating with many different landlords, enterprises can sign one master service agreement with WeWork.

Turnaround driver 2: Management change

Sandeep Mathrani is a disciplined operator and has previous turnaround experience. He took over a distressed retail estate GGP in 2010, when the company’s share was trading at $0.37 per share, $370m market cap and $22B debt. He subsequently sold 100 assets in 8 years and exited to Brookfield for $15B in 2018. In addition, Sandeep was a landlord, so he had been on the other side of the negotiation table and understood various stakeholders’ interests. This helps when WeWork renegotiated over 200 deals during COVID. Sandeep is 58 and the WeWork turnaround could be an important part of his operating legacy.

Turnaround driver 3: Asset disposal

WeWork is rightsizing its real estate portfolio to regain focus. During Covid, we estimate that WeWork exited 66 locations and amended 150 - 200 lease arrangements that resulted in a significant reduction in long-term liabilities.

WeWork’s economics are highly sensitive to occupancy rates. Occupancy is a function of mature and non-mature location mix, flexible office demand and WeWork’s value proposition vs peers.

In 2019, WeWork had 420 locations that opened for less than 24 months. On average, 70% occupancy is required to breakeven. Cutting 66 weakest locations or most expensive long-term leases would drive the average occupancy up and create better overall economics. This is because the remainder of the locations would have much higher average occupancy rates.

Exiting 66 weakest locations or most expensive long-term leases would drive the average occupancy up and result in higher margin across the portfolio.

Mix shift matters: Location contribution margin would improve to 24% in top markets and 32% with a higher portion of enterprise members.

Turnaround driver 4: Cost reduction

To streamline its bloated expense structure, WeWork has shrunk its workforce by 60% and cut many experimental growth projects. As a result, selling, general and administrative expenses, as well as, growth and new market development expenses are trending down significantly, from 86% of revenue in 2018 to an estimated 50% of revenue in 2019.

Turnaround driver 5: Potentially higher demand for flexible workspaces post-COVID

At the peak of the pandemic, nearly 50% of Americans have been working from home, up from 3.5% prior to 2020. Google, Salesforce, Facebook and PayPal are among the companies extending remote working to at least the second half of 2021.

However, a dozen studies suggest that long-term working from home has a negative impact on people. For example, 56% of people report increased anxiety (Forbes) and 45% of people are less productive (Eagle Hill Consulting). It is also more difficult for employees to collaborate and interact across different functions, as people retreat to their own functions to get their daily tasks done. CivicScience poll of the New York City metro area shows that 76% of respondents believe that the office is an important place for collaboration and innovation. The ability to train new employees has also degraded as a result of not being in the office.

A recent Gensler U.S. work from home survey on large companies indicated that the majority of workers would prefer a hybrid work model. Out of 2,300 employees surveyed, 81% would want to return to the office while keeping the benefit of flexibility.

81% of employees want to go back to the office full-time or part-time.

Source: Gensler.

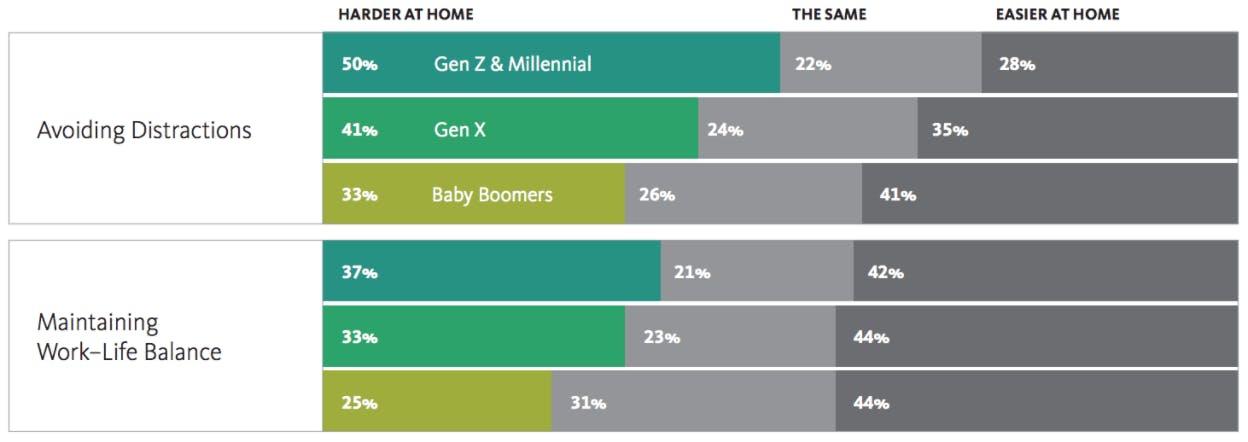

There are also surprising generational differences towards remote working. Despite being more tech-savvy, younger generations find it more difficult to work from home. Young people are less likely to have dedicated working space at home, more likely need context, structure, visibility in their work and want to socialize with colleagues. In contrast, the baby boomers, who tend to have larger homes, longer commute, no young children, hence, lower incentive to work in an office.

The younger generations find it harder to avoid distractions and maintain work-life balance than Gen X and Baby Boomers.

Source: Gensler.

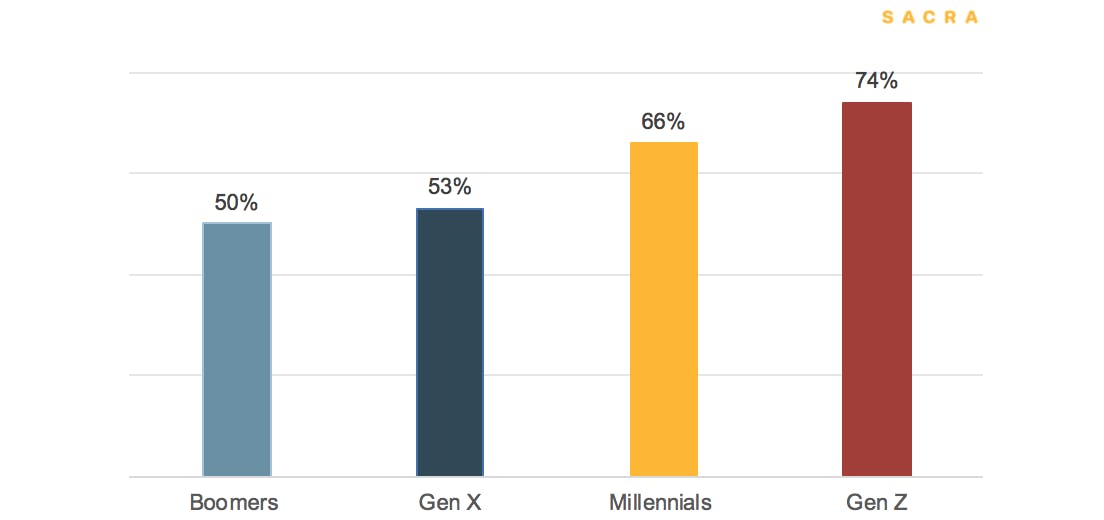

Similarly, a survey commissioned by Smartsheet shows that 66% of millennials and 74% of Gen Z feel less informed about company updates since they started working from home, compared to only 50% of Boomers and 53% of Gen X feel less informed.

Surprising generational gap: 66% millennials and 74% Gen Z feel less informed about company updates since working from home.

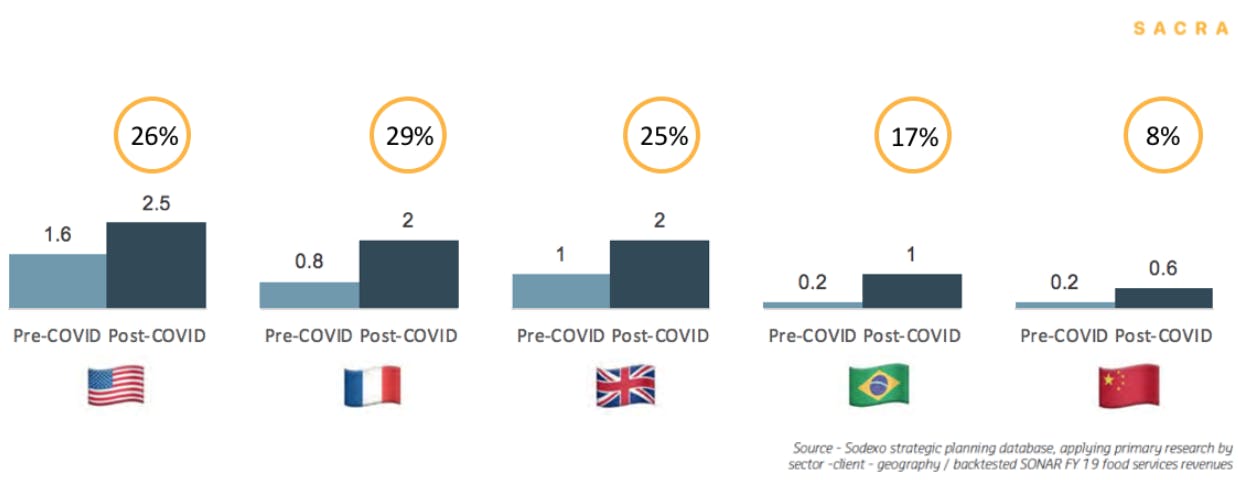

Primary research from office food catering company Sodexo suggests some permanent increase in working from home, with a projection of 25%-30% reduction of time spent on average at the office. This translates to one to two days of working from home for the office population in the west.

In the US, France and the UK, an average of 27% projected reduction of time spent at the office by employees as a result of Work from Home policies.

Source: Sodexo.

The changing circumstance may become the catalyst for a structural trend of flexible workspaces taking share from traditional landlords. There is early evidence that corporate demand for shorter leases is picking up. During the pandemic, WeWork leased 3.5 million square feet (“MSQF”) to enterprise clients. For example, WeWork has secured large deals from TikTok, Mastercard, Microsoft, Citigroup and Deloitte.

Fast-growing companies use WeWork as an overflow mechanism to adjust their office space up and down according to business outlook. Similarly, the current uncertain outlook for the economy can cause more companies to seek agility and adopt a flexible approach to accommodate their changing needs.

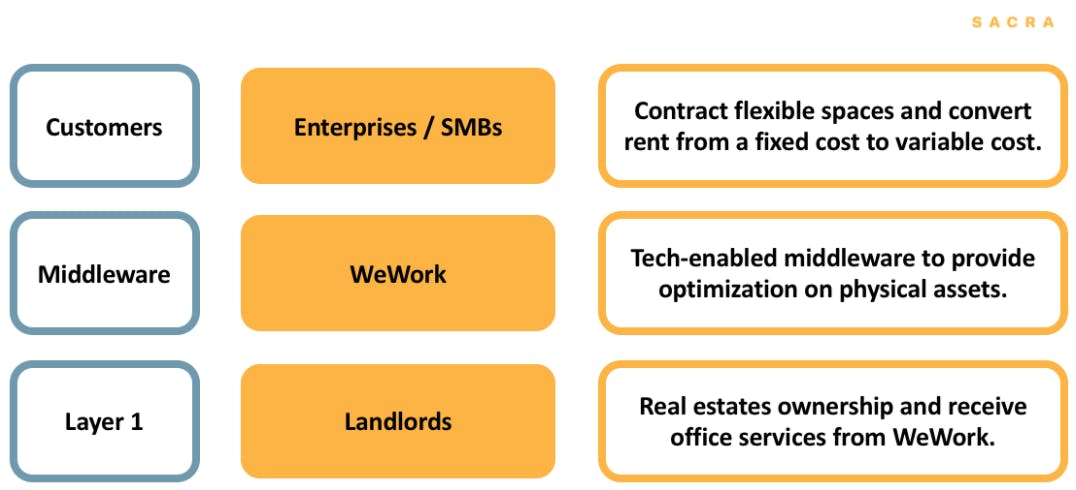

From the corporate clients’ perspective, new lease accounting standards may further incentivize enterprise CFOs to sign flexible and short-term contracts. This is because instead of taking on lease liabilities on the balance sheet, WeWork contracts can be recorded as an operating expense. Fundamentally, WeWork contracts change rents from fixed costs to variable costs for its customers.

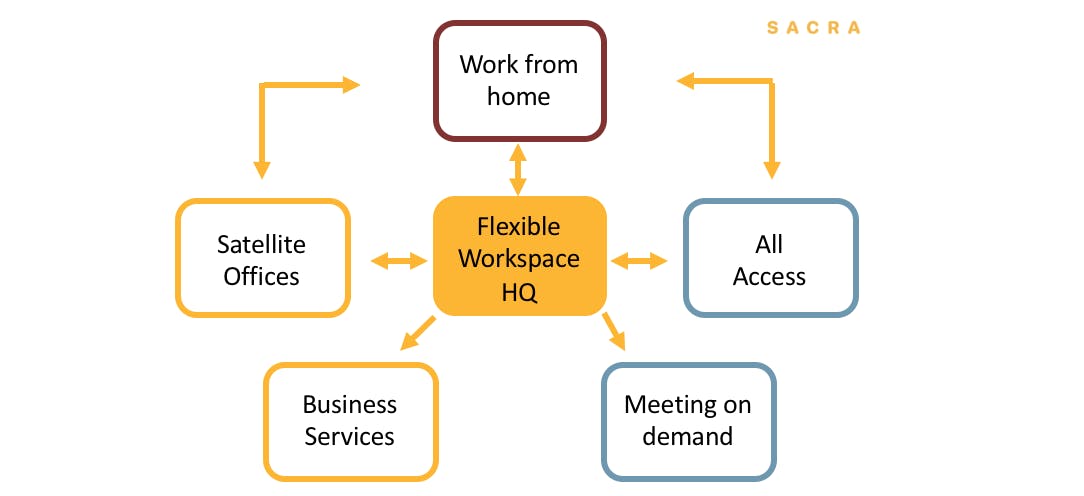

Flexible workspaces keep the benefit of in-person collaboration and flexibility.

As lease expiries occur over the coming years, CBRE expects that more office occupiers, larger ones, in particular, will adopt a ‘hub and spoke’ model to create an agile real estate portfolio. In a more distributed world, employers who offer flexibility that reduces commute times and improves employee wellbeing will be better placed to attract and retain talent.

3. WeWork’s plan to become the tech layer of commercial real estate

With the new management’s focus and the right execution, WeWork's turnaround could put it back on the kind of stable footing necessary to pursue its vision of being a workspace ecosystem provider.

The core differentiating factor of flexible workspaces is less about cost savings in rent but more about an end-to-end business solution platform. The foundation of the workspace services, such as internet connection, web security, access control and amenities, are somewhat a commodity business. The “killer app” in the office space is the capability to connect people with the shared interests in the same space, to facilitate learning and business opportunities.

Despite the large cost cutting, WeWork continues to invest in community services, such as WeWork Labs and Business Solutions. WeWork Labs is a community manager app. It is a digital platform connecting members and mentors based on their interests. It provides cross sector incubator services to support companies to acquire skills, meet peers and experts.

If WeWork can leverage its physical locations and build a tech-enabled layer on top, it could reshape the real estate stack with itself as a middleware to connect people and optimize spaces.

WeWork could become a middleware in the office space.

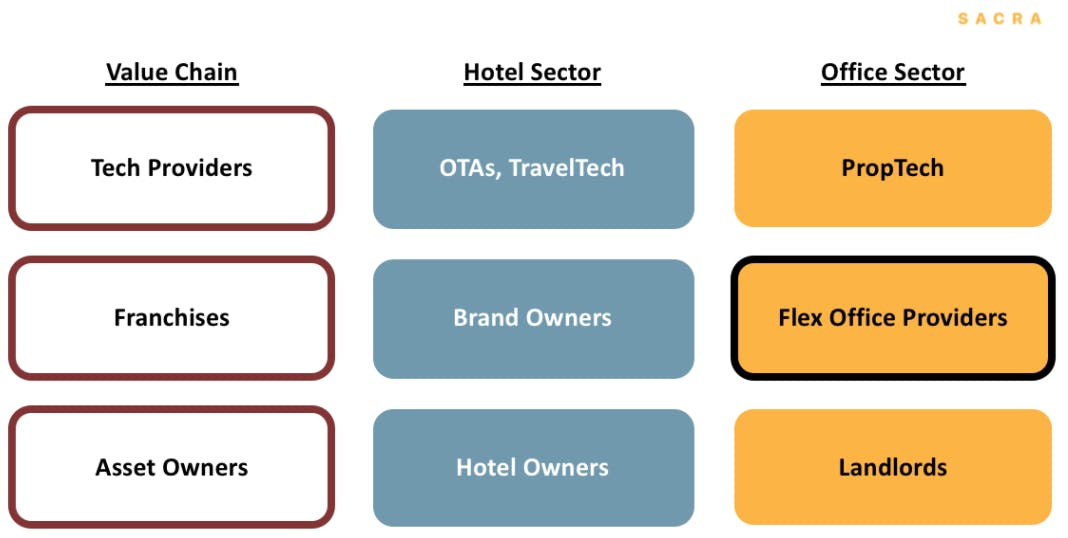

What’s happening in the office sector mirrors what happened in the hotel industry over the last few decades: the value chain is being separated into specialized entities with different investors and different return expectations.

REITs own hotel assets that are not customer-facing or have distribution. Hotel brands typically do not own buildings, but they own franchises, manage distribution and design layouts. Online travel agencies (“OTAs”) aggregate supply and provide better technology.

Hotel brand owners began to build their own hotel management software in the 90s, but it never took off. Then, online intermediaries, such as Booking.com, Airbnb and Expedia, came along and created digital platforms with strong network effects and better technology.

The future flexible office value chain could consist of landlords, flex office providers and a top layer of tech providers.

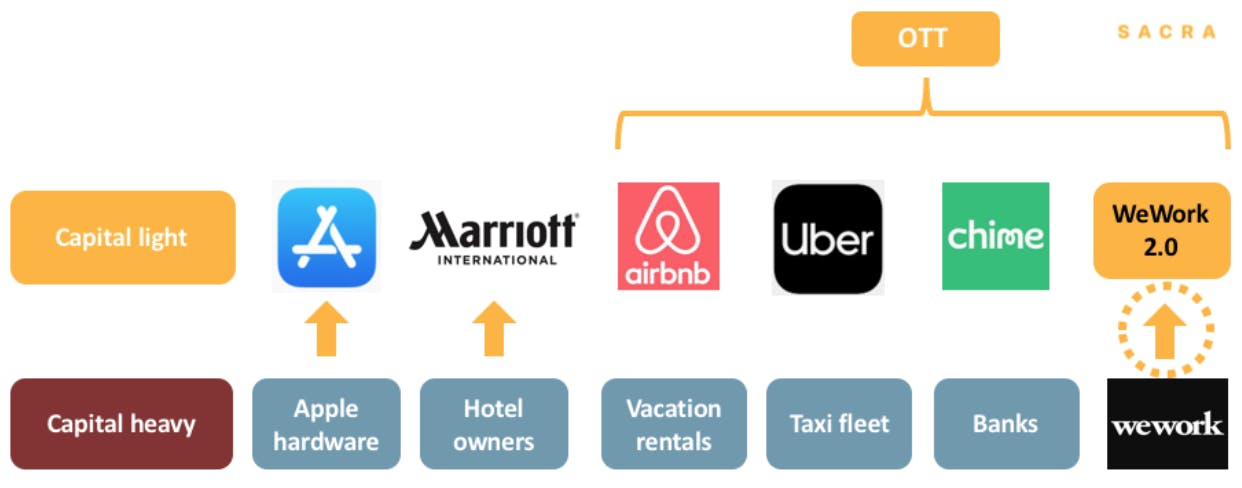

WeWork’s new capital light strategy is similar to how hotel companies transition from owning and operating buildings to a capital-light franchise model. We believe “space-as-a-service” is not as far-fetched as it is perceived. WeWork could become the over-the-top (OTT) player in the workspace. It provides services over the top of infrastructure owned by others.

Airbnb, Uber and Chime build a tech layer on top of existing capital-heavy infrastructure to connect the customers and service providers.

Examples of capital-heavy to capital-light transformation.

Apple and Marriott International are great businesses because they transformed their core offering from capital-heavy, low barriers to entry, competitive products to capital-light brands with pricing power and strong distribution.

WeWork could embark on a similar vision post its turnaround. The franchise model is a step in the right direction.

WeWork 2.0!

However, without the burden of a heavy balance sheet, next-generation PropTech companies are already emerging, from innovative booking systems to sensor-powered automation and smart devices, such as Switch Automation, SensorFlow and Flowscape.

These digital-native companies may be more agile, particularly now that WeWork has cut down on its innovative tech projects.

If the office sector follows the trajectory of the hotel sector, then these kinds of top-layer technology providers with strong network effects would capture most of the value.

Just as OTAs and Airbnb captured mindshare by providing better technology and more choices, these office space top-layer companies are positioned to capture value by providing data analytics to optimizing occupancy and reducing search costs.

The ultimate tragedy of errors may be that WeWork’s original business model was simply ahead of its time.

The future of WeWork

A recalibration of expectations on the future trajectory of WeWork is overdue. Beyond the current negative sentiment, WeWork has rationalized its growth plan and the fundamentals of the core business are improving. On top of this, shifts in industry demand to a more distributed workforce can provide the tailwind WeWork needs to revive itself.

On balance, the equity portion of WeWork resembles the risk-return of a call option. Given the high fixed cost nature of the business, operating leverage is terrible in a downturn, but, once the cycle turns, it helps operating income disproportionally.

Similarly, the flip side of a high debt-to-equity ratio is that the financial leverage crafts a high reward for the equity holders. For example, at an $18B enterprise value, with $15B debt plus leases, an 5% increase in EV would result in a 33% increase in equity value.

In terms of future growth opportunities, flexible workspace comprises only 3-5 % of the total office footprint in the US, 12% in the UK and low single-digit worldwide. The outlook for growth in the sector appears high. Total space used by flexible working has grown at a CAGR of 26% in the US since 2010.

By 2030, CBRE expects the flexible workspace to be 13% of office footprints in the base case and 22% in a high growth scenario. JLL is even more bullish and expects the ratio to reach 30%.

The concept of a flexible workspace is not new. During the previous cycles, the idea was entertained but never fully adopted on a large scale. However, this year, the world has already begun hybrid ways of working. Also, cloud-based collaboration tools are better developed and implemented today than ten, twenty years ago.

The combination of these factors could transform WeWork’s position in the value chain from a marginal provider to an integrated, tech-enabled ecosystem coordinator.