Tender Offers in 2021: Underpriced and Undersubscribed

Jan-Erik Asplund

Jan-Erik Asplund

Where specifically noted, some of the analysis and data utilized in this publication was provided in aggregated and anonymized fashion by Carta with at least 5 data points for any aggregated statistics shown. Companies who have contractually requested that Carta not use their data in anonymized and aggregated studies are not included in this analysis.

We received no compensation for the writing of this report, and the analysis of the data is our own. If you have a data set you’d like us to write about, shoot us an email at founders at sacra.com.

The tender offer problem

For private companies that reach a certain size, the tender offer has become the most common way to offer liquidity at scale. As companies head towards the public markets, particularly those planning a direct listing, tender offers also provide valuable guidance on what their stock is worth. The problem with tender offers is that they underprice a company’s stock, sometimes drastically.

Tender offers serve the vital purpose of providing a scalable route to liquidity for employees at fast-growing companies.

In late 2019, Asana employees sold stock¹ into a tender offer priced at $15.82. Less than a year later, the company would go public at $28 a share.

In February 2020, Snowflake employees sold² into a tender at $38.77 per share—in September, the company would go public and hit $253 on its first day of trading.

Tender offers promise to help employees of private high-growth companies de-risk and diversify, but chronic underpricing means that selling into a tender frequently means leaving large sums of money on the table.

In July 2019, Unity employees sold³ into a tender priced below their contemporaneous Series E round. 16 months later, the stock’s value would be up 400%.

Today, we’re seeing low participation rates of 37% across tender offers and 83% of all transactions priced at or under the price of the last round of funding.

We analyzed a data set of 64 tender offers totaling more than $3B in transaction volume. We found that not only are employees still the “last to liquidity”, they still need to go to the public markets to get competitive pricing on their stock.

Join our list for more of our exclusive private markets research and company coverage.

Success!

Something went wrong...

How 83% of tender offers get priced at or under the price of the last round

For investors, tender offers can help win deals and get a larger percentage of ownership than they could otherwise—and, in the vast majority of cases, they can do so at or below the price of the last round of funding.

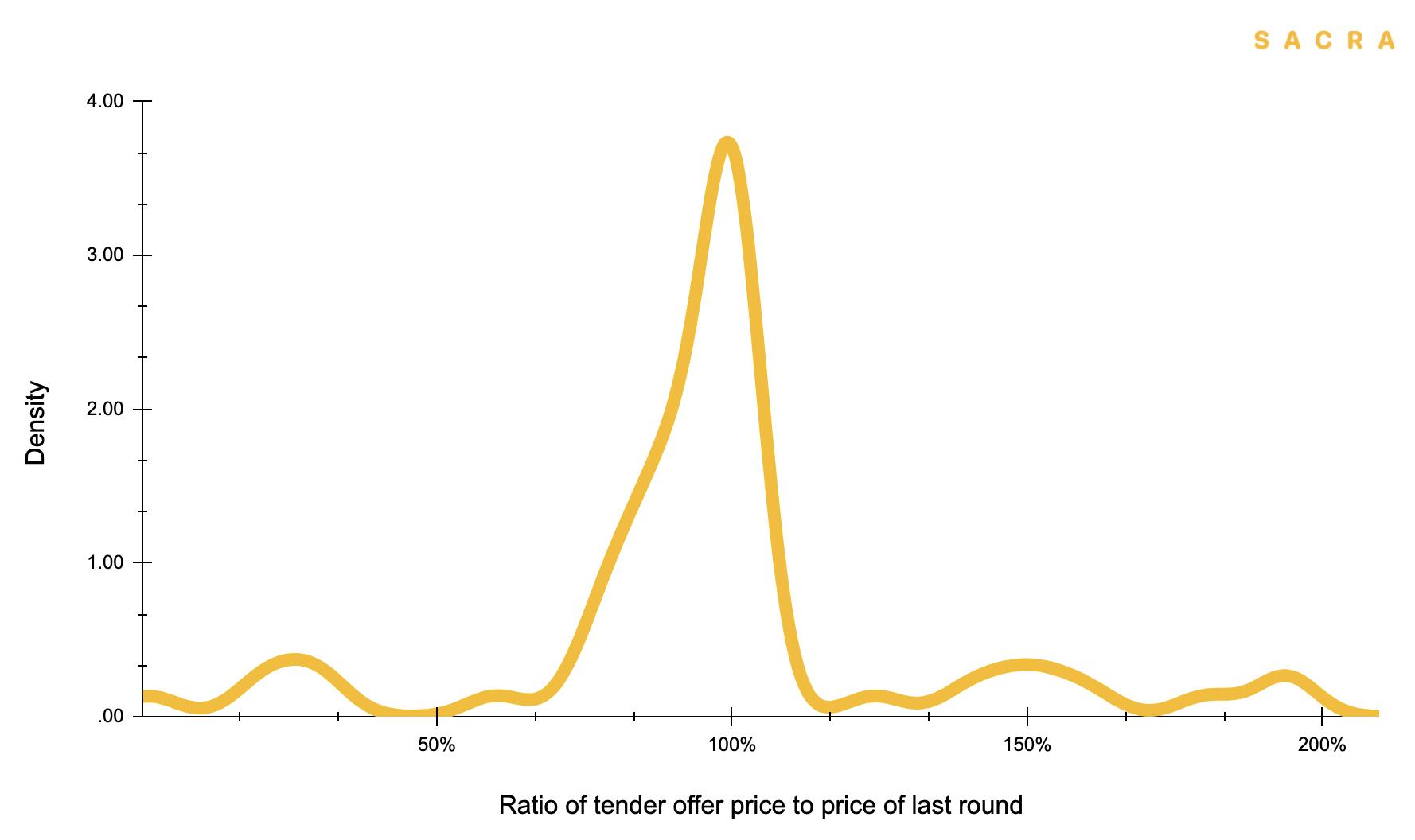

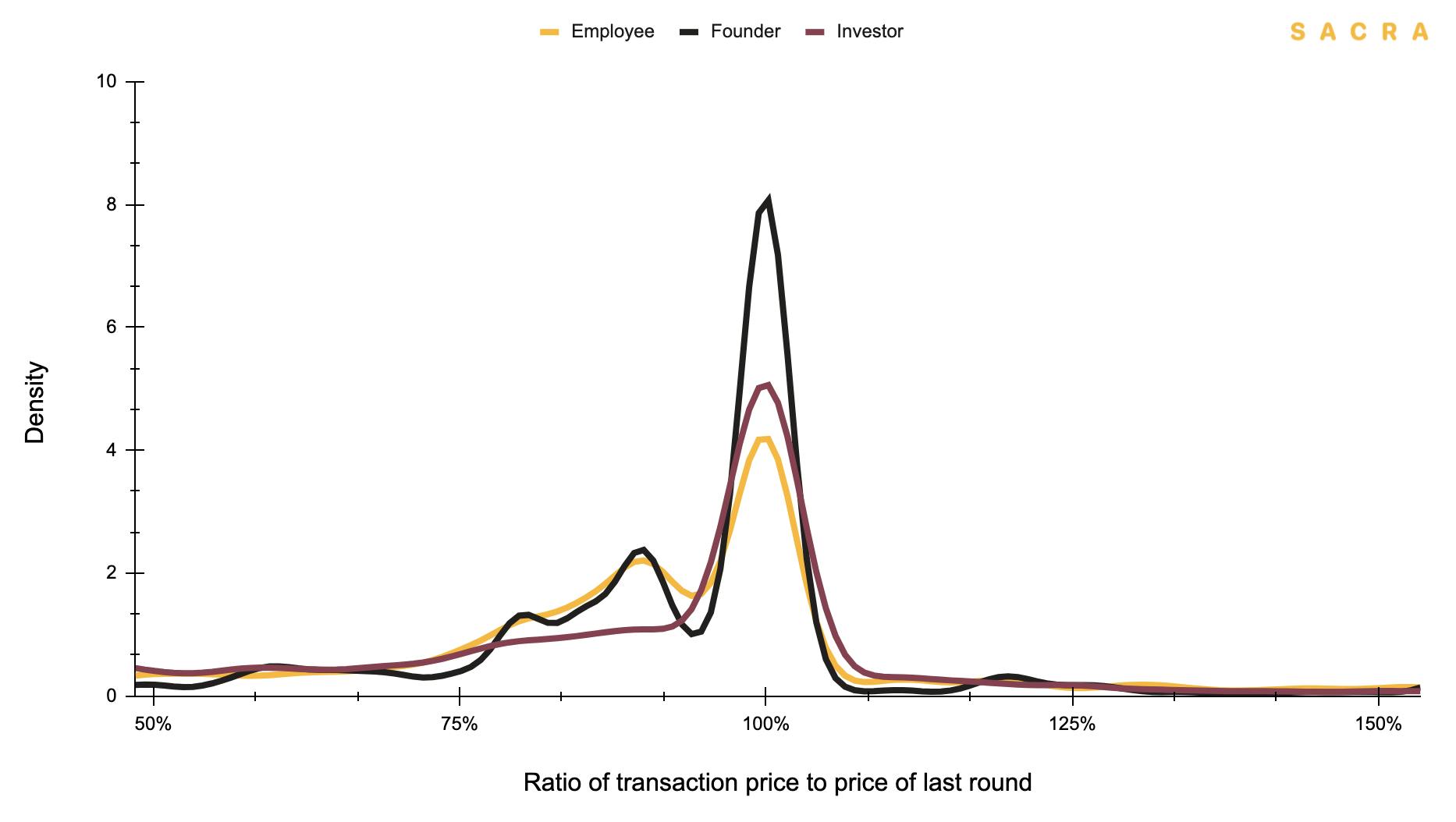

Most tender offers are priced at a 1:1 ratio with the price of the last round. 83% are priced at 1:1 or under. (Aggregated and anonymized data from Carta)

We’re seeing tender offers priced at the price of the last round or lower in 83% of all transactions, with 15% priced at a 20% premium or better and less than one half of one percent at a 2x premium or better. The ratio clusters at 1:1 with the price of the last round.

Pricing tender offers based on the last round’s valuation is convenient, but it misprices high-growth companies. By relying on the last round’s valuation, all new growth and changes to the company’s fundamentals are not priced in, and employees and other shareholders end up selling at a discount.

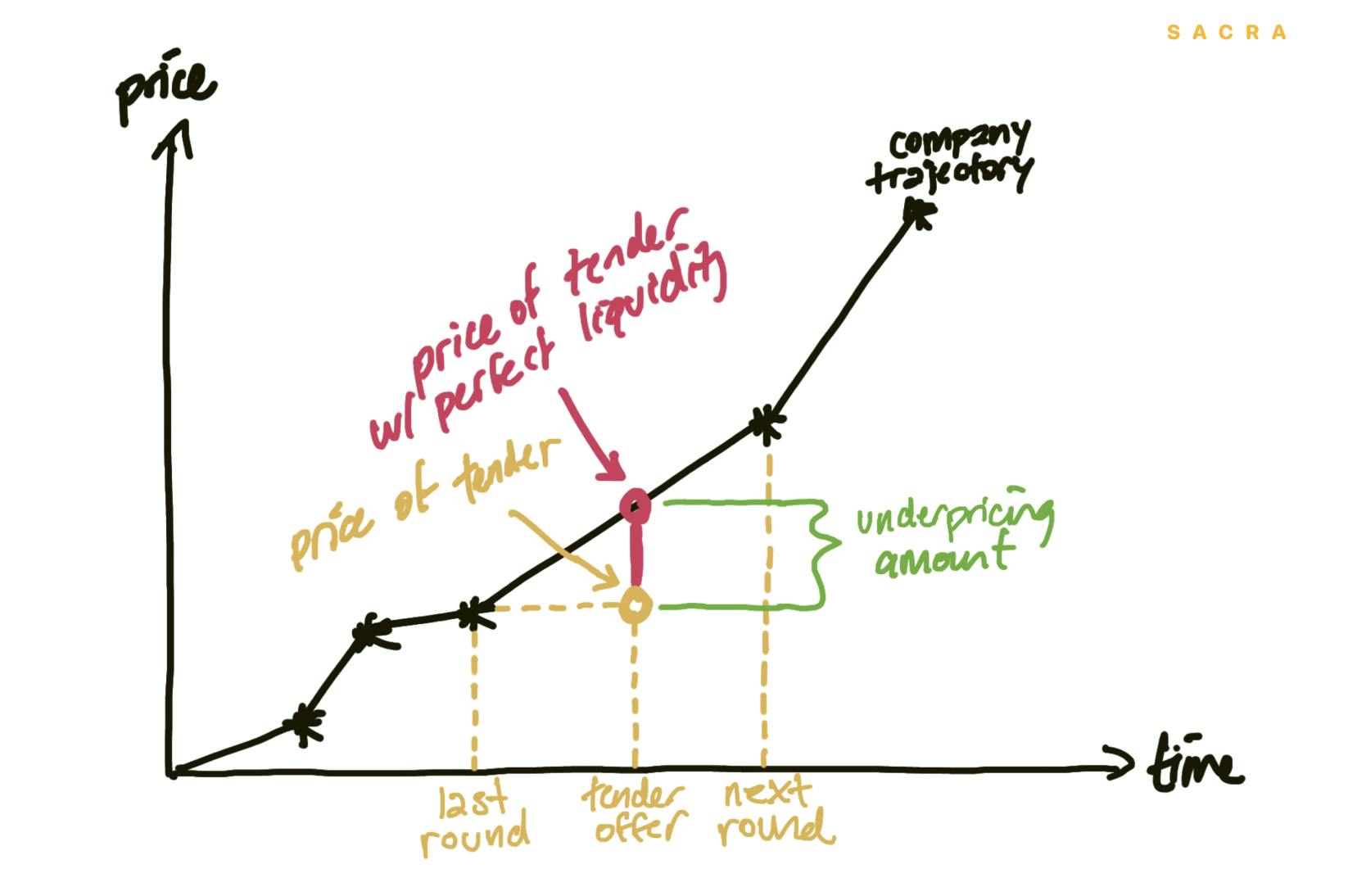

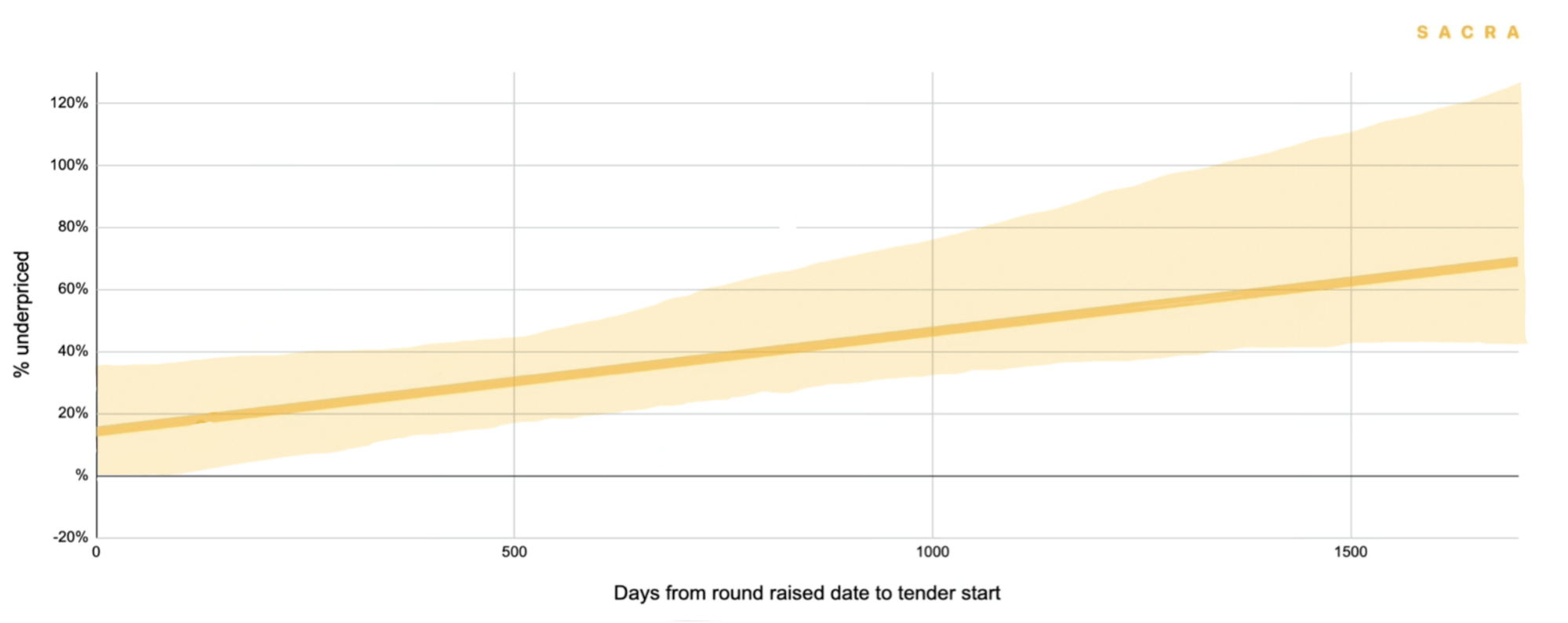

Pricing tenders offers based on the last round of fundraising underprices companies in proportion to their growth and progress.

To assess the degree to which underpricing is prevalent in tender offers, we compared the discount or premium on the price of the last round for each tender offer with a linearly interpolated price based on the amount of time passed since the round (“price of tender with perfect liquidity” in the graph above). We found nearly every tender offer in our dataset to be significantly underpriced, with a large majority underpriced by more than 10%.

Across the data set, nearly every tender offer was significantly underpriced relative to where the Company traded in a future financing round. (Based on Carta data)

Every year, that’s hundreds of millions of dollars being transferred from shareholders to the investors on the buy-side of these tender offers. Rather than a mechanism to help employees de-risk and diversify, the tender offer has become a way for investors to extract shares at cut-rate prices from those employees most desperate for liquidity.

Why participation in tender offers is under 40%

Underpricing doesn’t just hurt employees by reducing their overall returns from selling into tender offers. It also dampens participation rates—calculated as the portion of shares sold into a tender by a stakeholder divided by the portion of shares eligible for sale—keeping employees from getting liquidity.

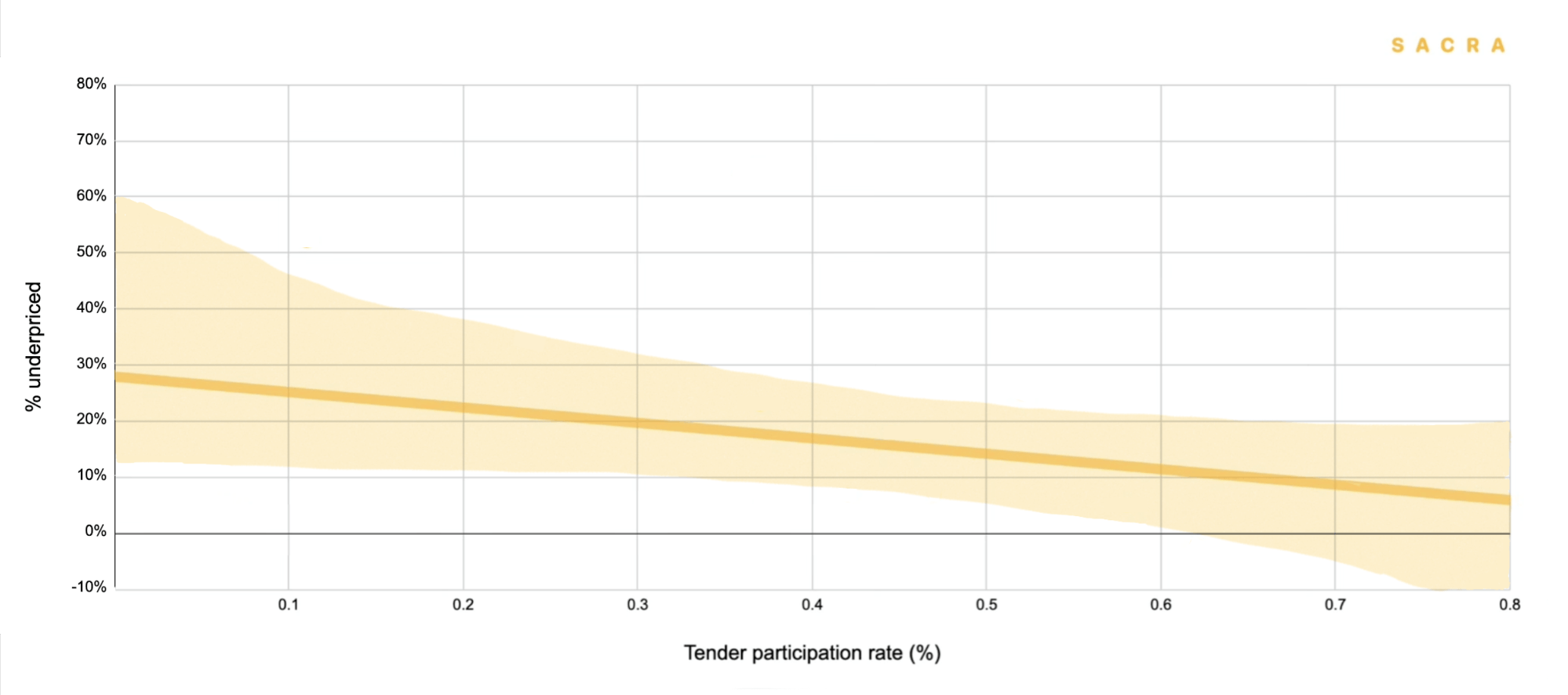

Less underpriced tender offers see higher participation rates (i.e. employees selling a higher percentage of the shares they are eligible to sell into that tender), while more underpriced tenders see less participation. (Based on Carta data)

When we look at the data, there appears to be a direct relationship between tender offer underpricing and what percentage of their eligible holdings employees opted to sell. For the most part, tender offers that were less than 30% underpriced saw participation rates of between 30% and 50%, while tenders more severely underpriced saw their participation fall to between 10% and 30%.

The upshot of underpricing in tender offers was not just low employee participation, but low prices for employees selling stock compared to founders and investors selling stock in private secondary transactions apart from tender offers. When we looked at all secondary sales, including one-off and founder sales, we found that employees sold at significantly lower prices than founders and investors.

Across all secondary sales, investors and founders were more likely to be able to sell at a price closer to the price of the last round. (Based on Carta data)

All secondary sales tend to be at or under the last round’s price, but founders and investors were more likely to sell at a 1:1 ratio to the price of the last round, while employees were more likely to sell at a discount. These subpar outcomes may help explain why only 24% of employees ever exercise their options⁴.

Employees are the last to liquidity, while investors are the first

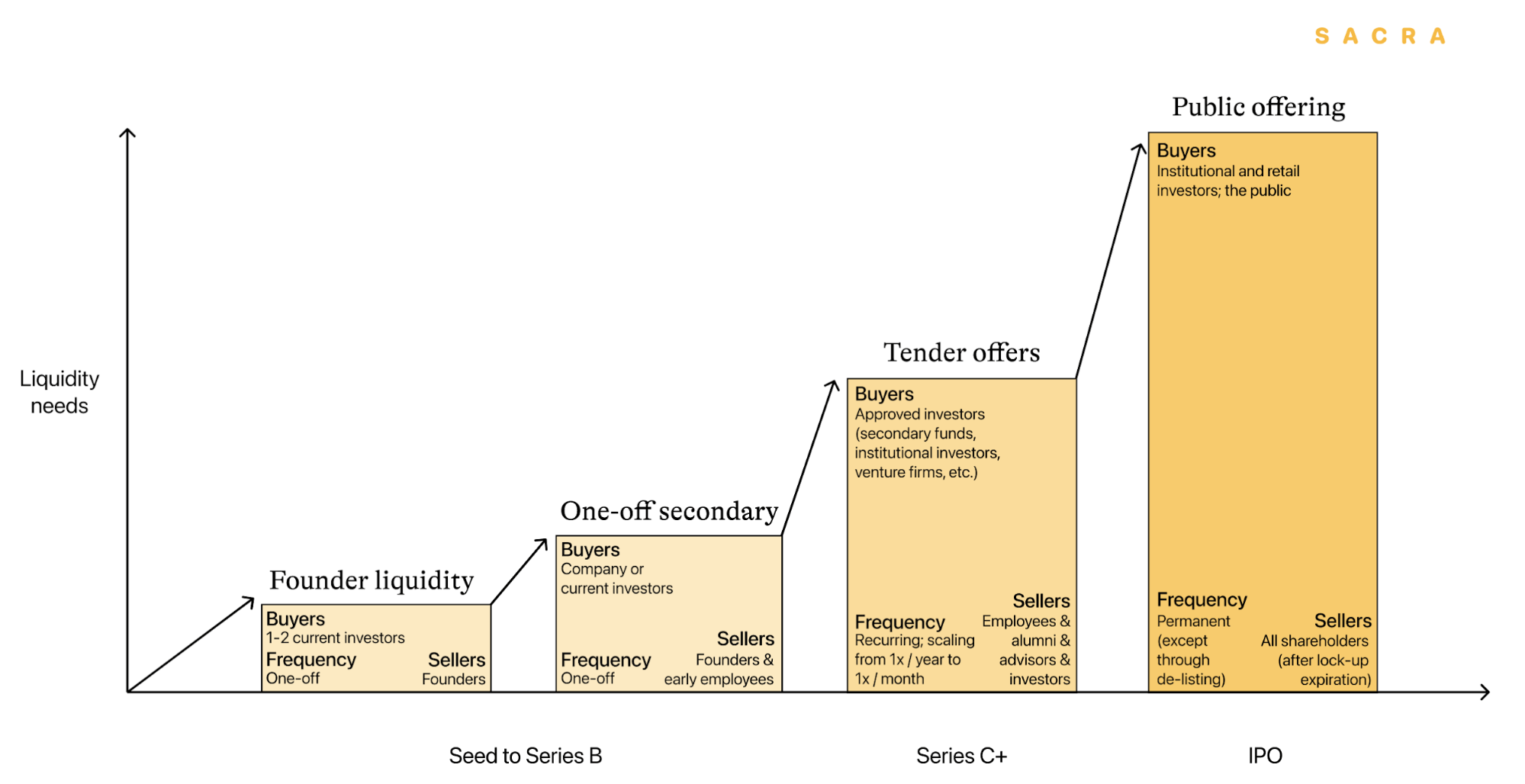

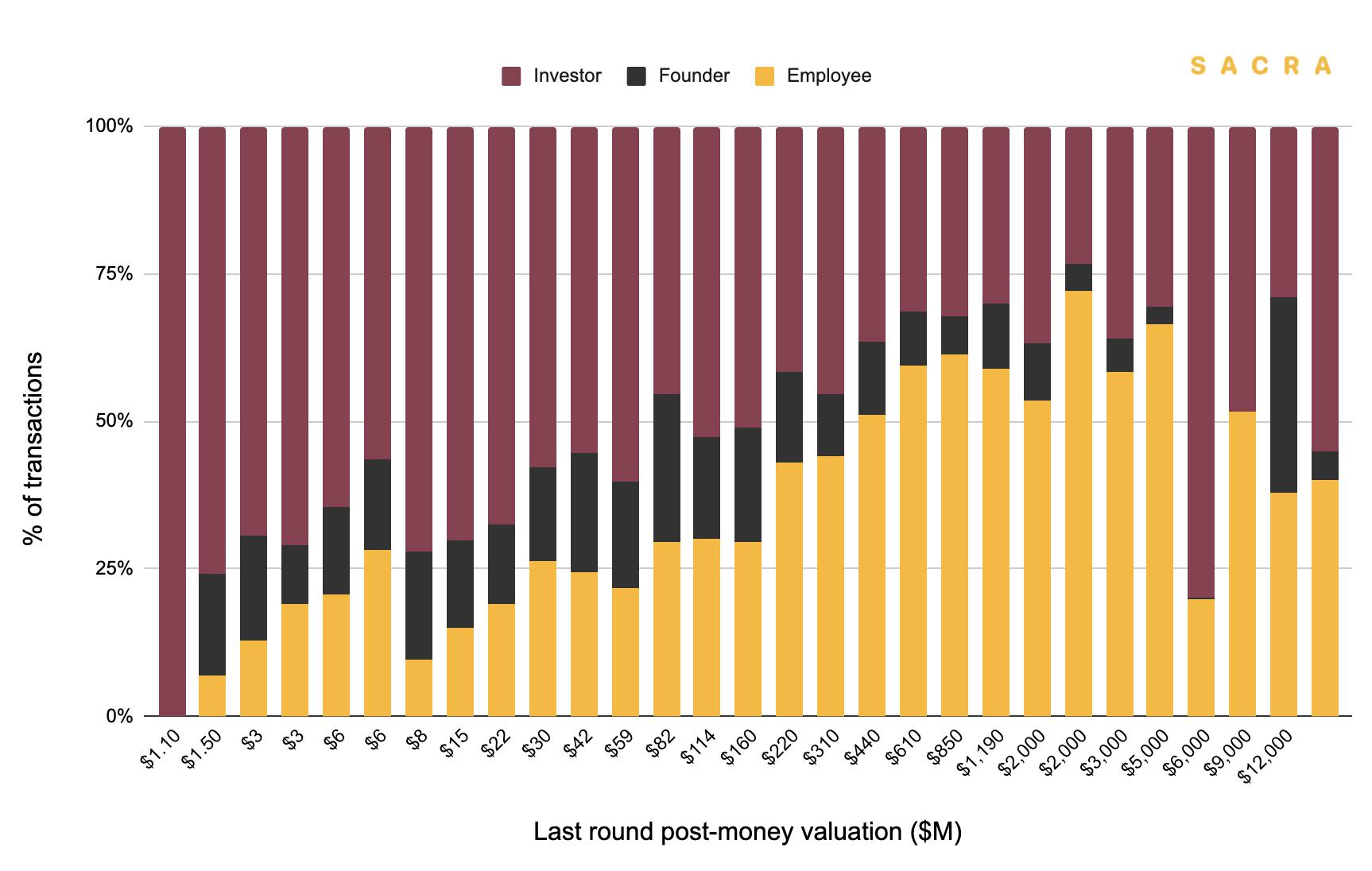

Across all secondaries, employees account for fewer transactions than founders and investors until companies hit $310M in post-money valuation. Founders and early investors sell from seed to Series B, while employee sales become more significant from Series C onward.

Over time, participation in secondary sales flips from primary investor-centric to primarily employee-centric. (Based on Carta data)

We analyzed the selling stakeholders in tender offer transactions across 28 post-money valuation buckets. Overall, investor sales made up an average of 50% of transactions, founder sales made up 15%, and employee sales made up just 33%. The brunt of investor sales come early. At post-money valuations up to $21M, investors are responsible for more than 70% of secondary transactions, while founders and employees sell in roughly equal amounts.

Meanwhile, 75% of all employee transactions take place once a company’s post-money valuation has exceeded $160M. In contrast, just 46% of investor transactions and 41% of founder transactions take place after that point.

This distribution of secondary activity reflects the reality that as equity has become more liquid, the benefits of that liquidity have accrued to investors, founders, and employees in that order. Investors have the ability to sell early, when a company’s stock is still exclusive. Employees, meanwhile, have to wait until the stock is more broadly available—and commands a smaller premium.

How to fix the tender offer

The state of liquidity has come a long way since the days when VCs would never agree to shareholders taking money off the table. Founders and angels in particular have much better access to one-off secondary sales to de-risk themselves and their portfolios. But as companies stay private longer and longer and look to provide liquidity to their early employees, the tender offers they use to do so at scale still leave much to be desired.

At the core of the problem is a lack of liquidity in the market for secondary shares itself. In almost all cases, tender offers are closed-door transactions with a buyer who is an existing investor and major stakeholder with control rights and a board seat.

For tender pricing to become responsive to the real value of companies, information about companies would need to be released and external investors would need to be invited into the process. With better information and investor access and up-to-date tender pricing, founders, angels, and most of all, employees at high growth private companies would benefit.

—

1. S-1

2. S-1

3. S-1

4. CNBC