The Privately-Traded Company: The $225 Billion Market for Pre-IPO Liquidity

Jan-Erik Asplund

Jan-Erik Asplund

The rise of private market liquidity

The traditional IPO has never had so much competition.

In 2020, special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) raised more than $30 billion to take companies public—triple what they raised in 2019.

Asana, Palantir, Roblox, Coinbase, Squarespace, Amplitude and Warby Parker all decided to go public via direct listings, following in the footsteps of Slack and Spotify.

Both SPACs and direct listings are hacks, freeing companies from the one-size-fits-all IPO and allowing them to cobble together their own “custom public offerings”.

They can either cede the ability to raise money and choose their shareholders (in a direct listing) in exchange for lower fees and less dilution, or pay more to a “sponsor” (in a SPAC) in exchange for an accelerated, more certain process.

The rising popularity of these hacks tells us is that the product-market fit of the public markets—which has been decaying for decades—is slipping.

The cumulative market cap of all listed companies may still be growing, but that value is increasingly concentrated in a handful of businesses. 6 companies make up half of the NASDAQ 100 today, while just 10 make up about 30% of the S&P 500: the most concentrated that index has been in 40 years. Most of the market's gains have also been driven by those mega-caps.

Being a public company is great for some, but not for all. And going public itself is less attractive than ever, which is why even some of the companies best-positioned to do it––high-growth, late-stage, venture-backed––are “hacking” the process.

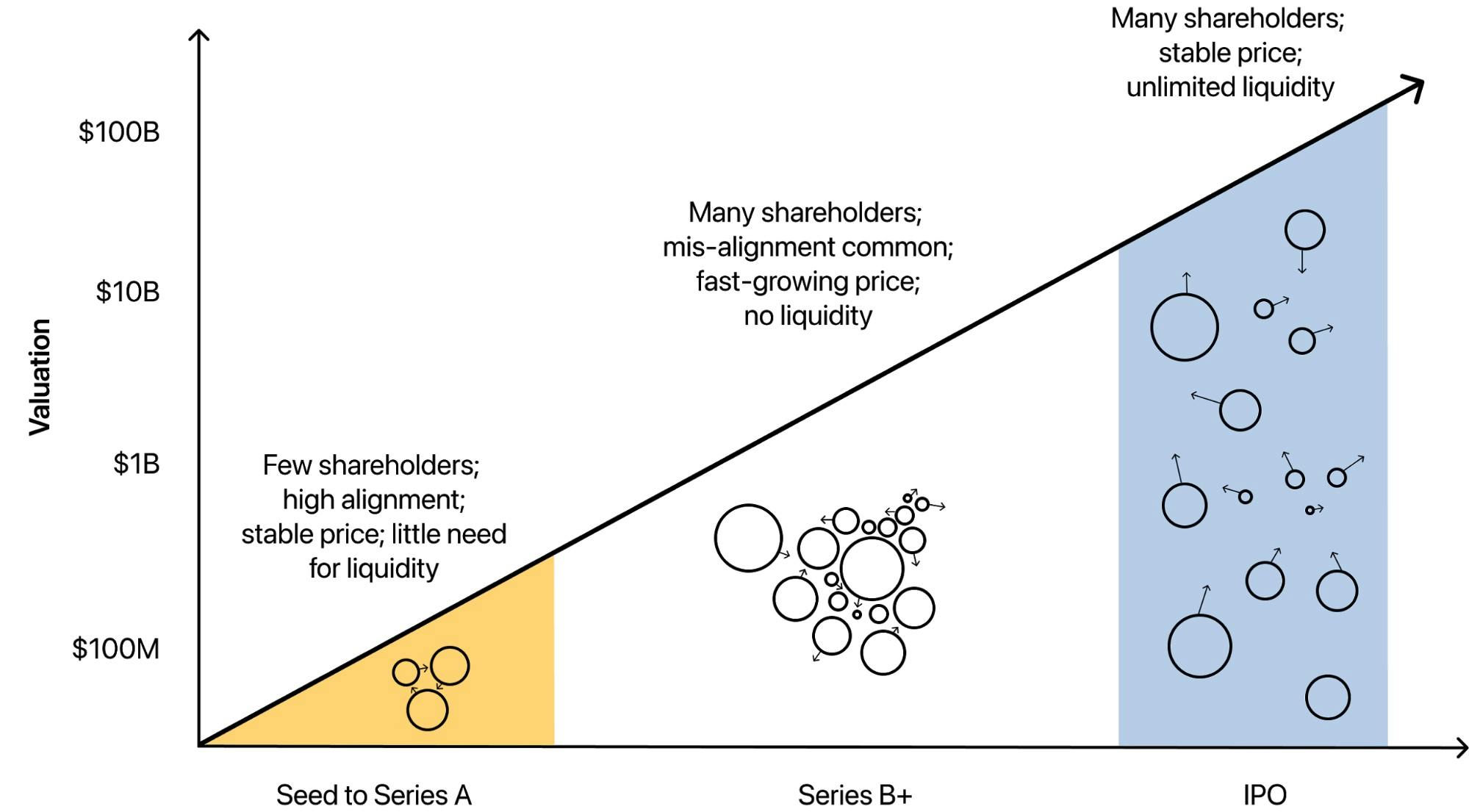

Underlying this lack of product-market fit is the massive gulf between private and public. Because there is no middle ground between the total liquidity of the public markets and the virtually zero liquidity of the private markets, going public is challenging even for the most prepared companies.

As companies get larger, their cap tables become more complex, and misalignments more common. Short of going public, they have limited ways to manage this.

Public market investors, who don’t have access to information or any kind of price history, don’t know how much to bid on their IPO.

At the same time, management teams, who haven’t needed the kind of discipline and reporting that’s expected of a public company, must undergo a massive and costly shift in how they operate.

Companies are increasingly using direct listings and SPACs as work-arounds for some of the most onerous aspects of the process. Or, they're staying private, taking advantage of huge inflows of capital into growth-stage investments from hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, investment banks, and others.

What's needed is a gradient of liquidity to fill up that middle region––a place between private and public where companies can slowly dial up their transparency, liquidity, and reporting.

These ‘privately-traded companies’ can use this liquidity gradient to get accustomed to the reporting and disclosure responsibilities of being a public company, while also solving some of the biggest problems that come along with being a private company at scale: fixing misalignments on the cap table, bringing institutional investors on without dilution, and cashing out early investors.

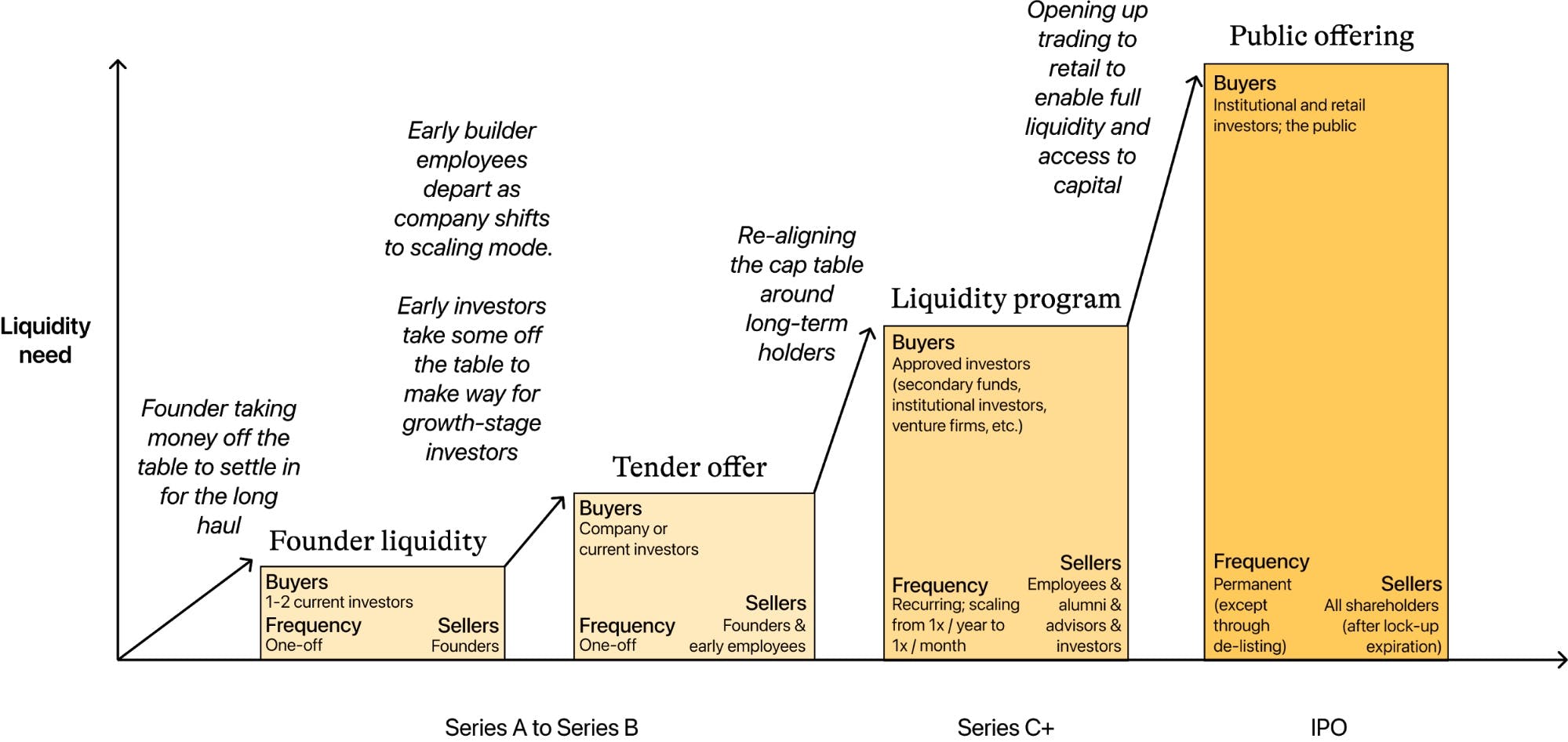

Liquidity is not one-size-fits-all, and different forms of it make sense for different phases in a company's lifecycle.

Working at a privately-traded company, employees will be able to to regularly sell some safe percentage of their stock pre-IPO, allowing them to trim part of their gains to help pay for a house or wedding, help deal with a sick family member, or even––one day––start their own company.

More liquidity in the private markets means more people who can use success to reinvest into the economy of entrepreneurship––in this way, ultimately, the benefits of this liquidity rebound to all of us.

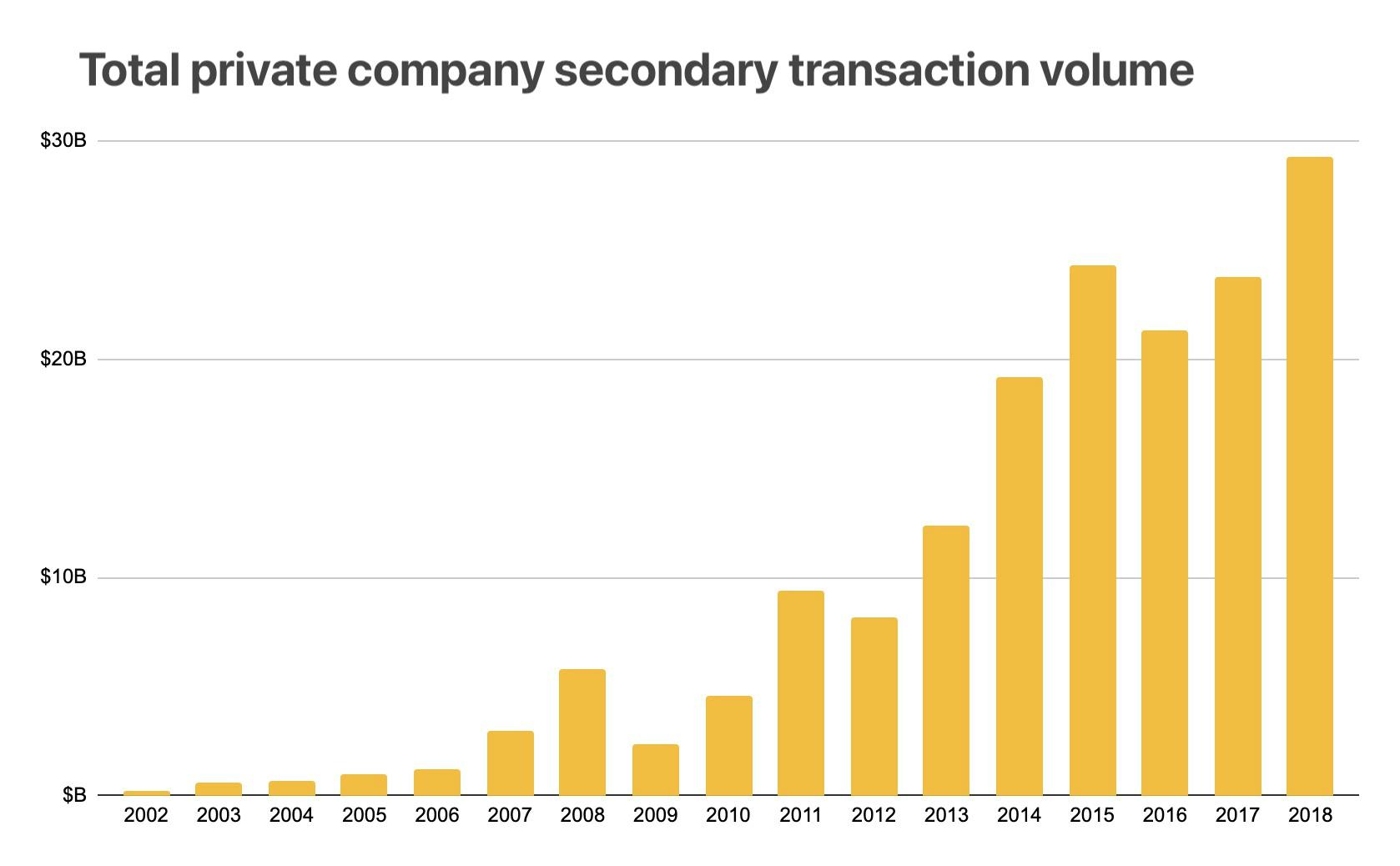

About $30 billion in private company shares changes hands every year—a 300% increase over the last decade, but still just 2% of the $1.5 trillion in value represented by all late-stage, venture-backed companies.

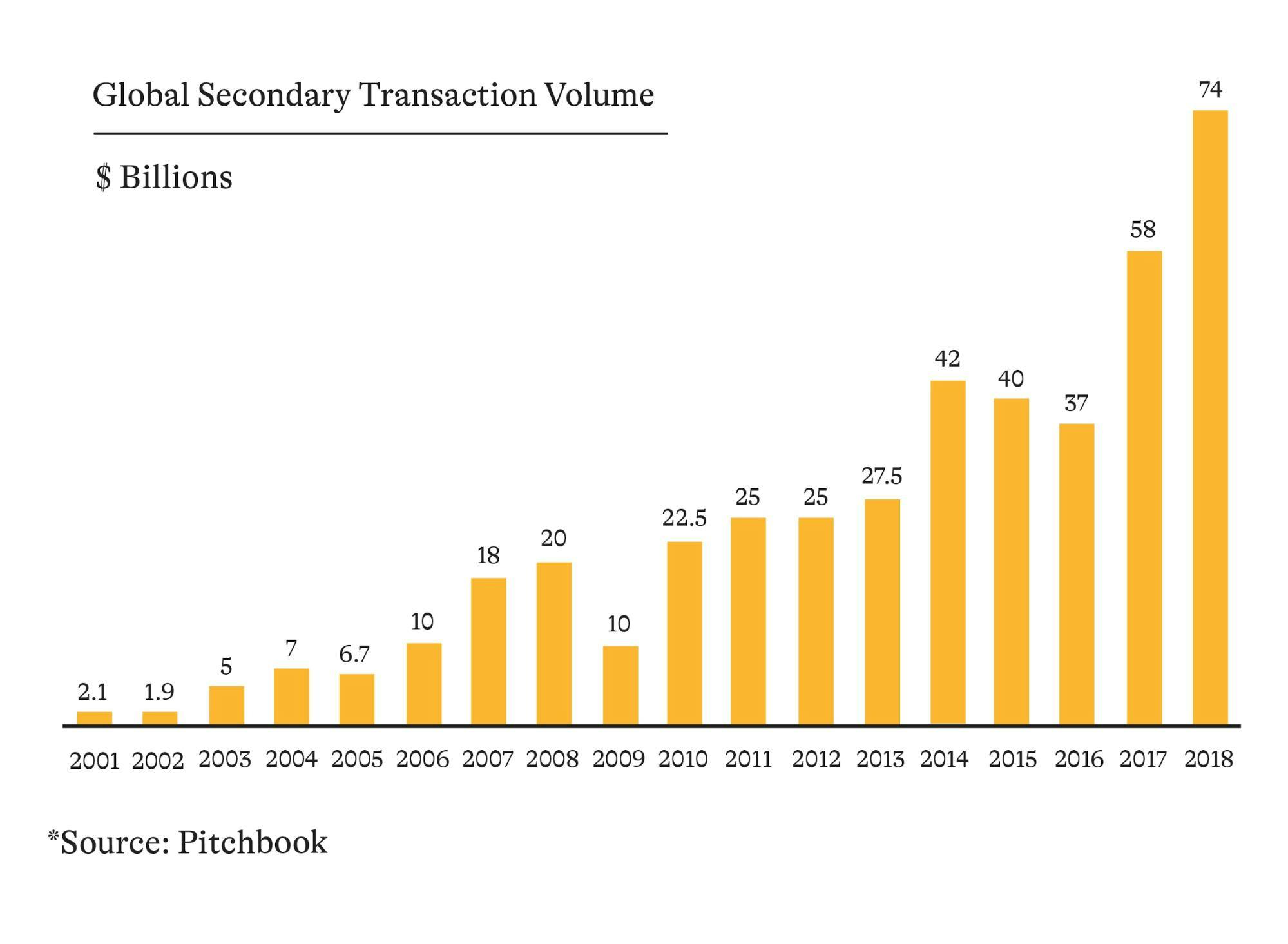

The market for private company secondaries surpassed $5 billion amid the liquidity crunch of the Great Financial Crisis. Since then, it has grown by 6x as companies have raised more money and opted to stay private longer.

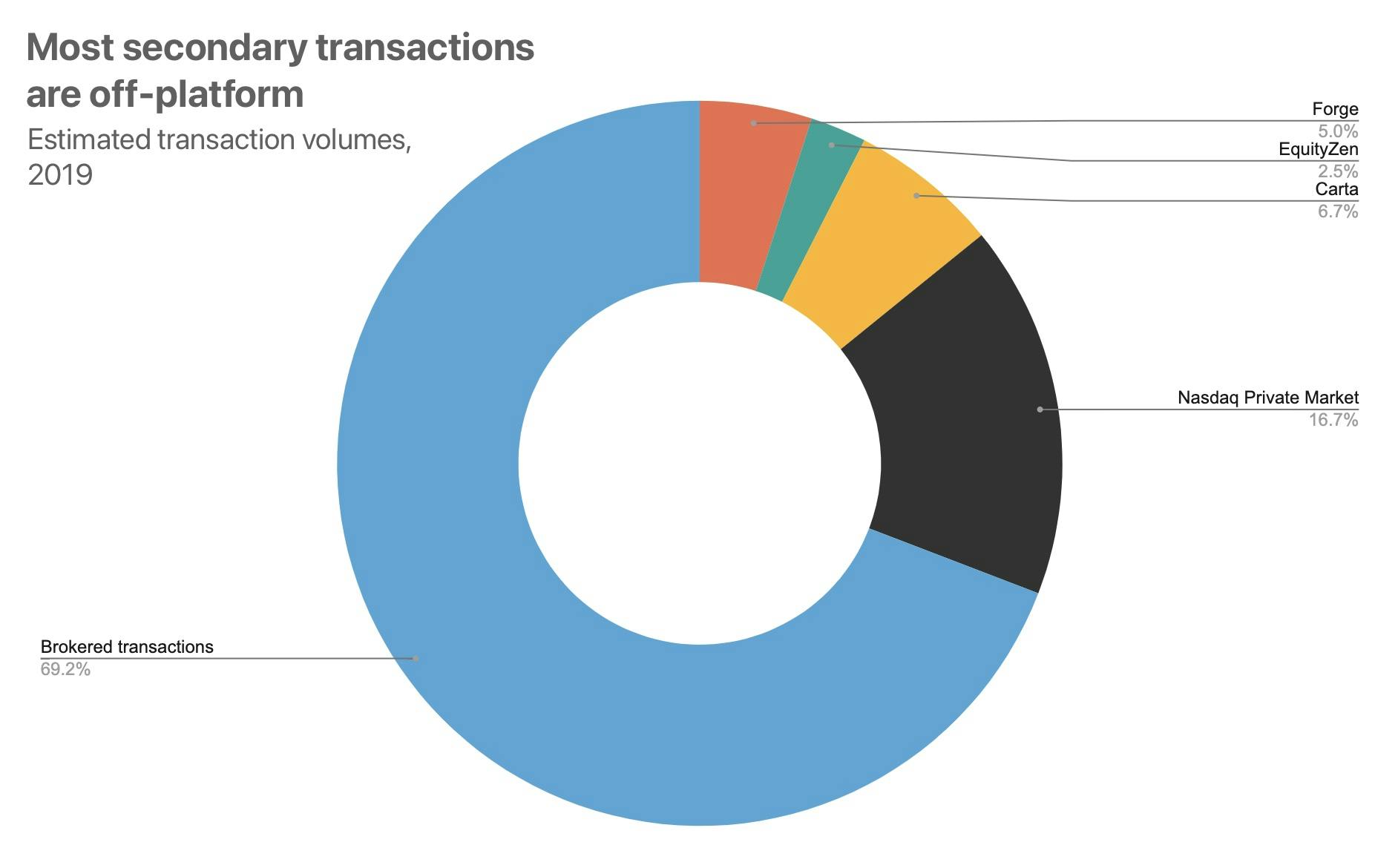

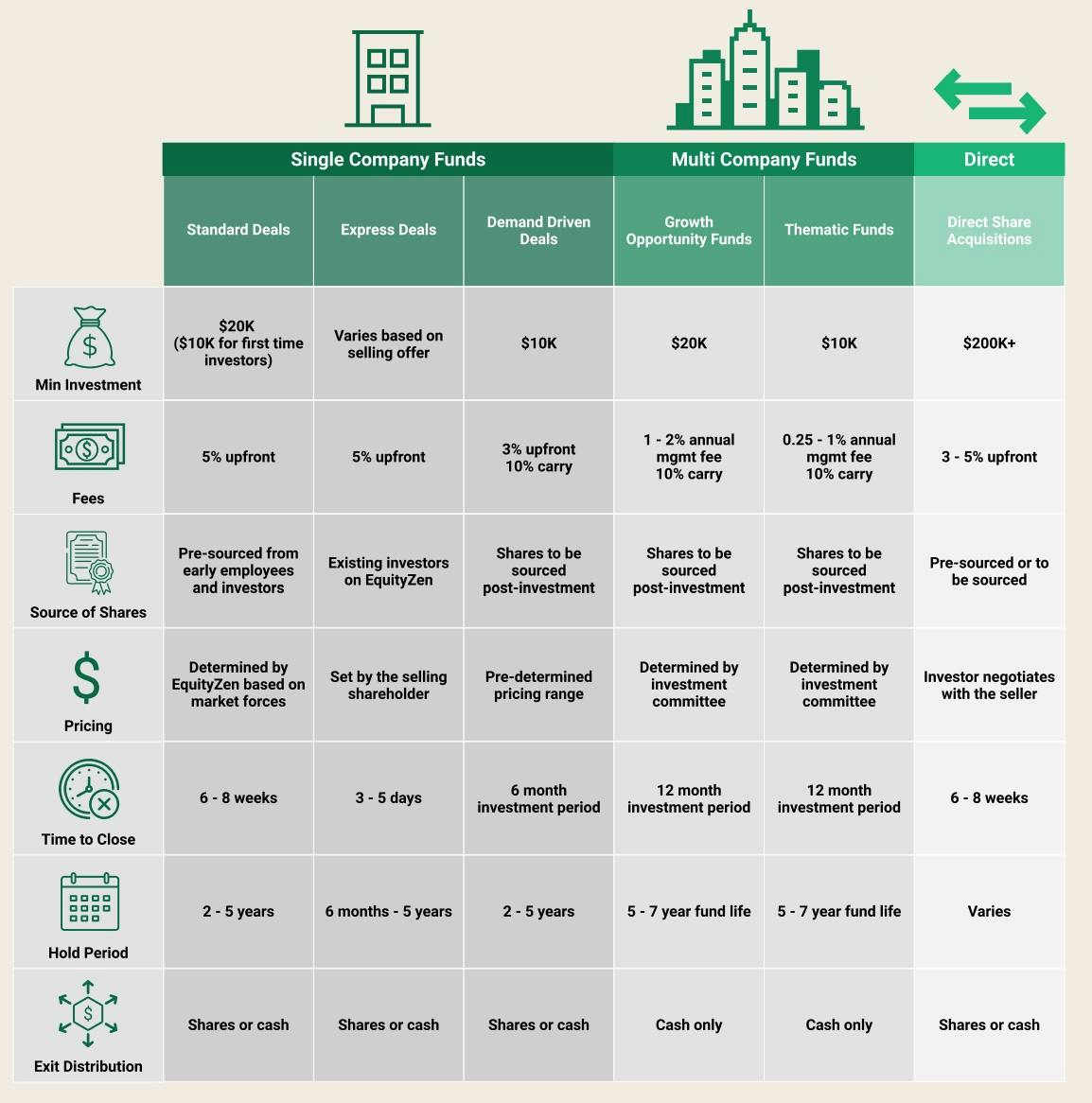

Most pre-IPO liquidity has traditionally been supplied by brokerages manually matching buyers and sellers. Today, the market for software-based, dis-intermediating solutions–while still relatively small and fragmented–is beginning to heat up, with Nasdaq Private Market facilitating issuer-controlled liquidity programs, platforms like Forge and EquityZen helping employees sell shares and investors buy them, and a wealth of other players emerging to attack the problem from different perspectives.

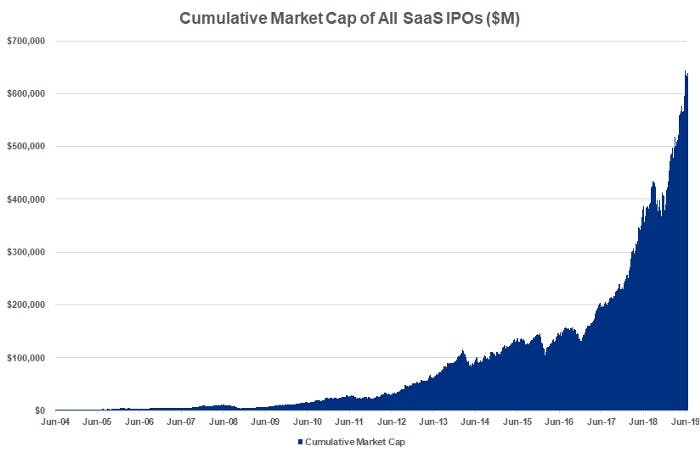

The value represented on the cap tables of the world’s venture-backed companies has been growing by more than 45% CAGR for two decades. As capital continues to flee from other asset classes into late-stage private companies and the gulf between public and private markets continues to grow, the need for liquidity will only become more and more acute, fueling demand for these kinds of offerings from employees, investors, and issuers alike.

Private market liquidity and the rise of the privately-traded company will have major implications for all the parties on the ownership graph.

A greater amount of liquidity in late-stage privates means that multi-stage, early-stage, and growth-focused venture firms need to reevaluate their strategies around exits, how they make investments, and how they structure their funds.

For issuers, it’s about taking advantage of a powerful new set of options that are emerging and exploring how being privately-traded can help them build stronger long-term businesses: how it can help them align their cap tables, better recruit, incent, and retain talent, and ease the transition into being a public company.

For family offices, hedge funds, pensions, endowments, and other traditional venture LPs, liquid private markets present an opportunity for an unprecedented degree of high-resolution investing in private companies, faster distributions, and access to a new, still largely untapped asset class.

No matter where you are on the cap table, private market liquidity is going to reshape the way that companies, investors, and markets operate.

In the short-term, it will take one of the most valuable, exclusive asset classes on the planet–late-stage, venture-backed, high-growth private companies–and allow investors around the world to access it.

In the long-term, technologically-enabled liquidity in the private markets could render the entire public market into an anachronism.

To see what this arc looks like and to understand how to best get positioned to benefit from it, issuers and investors need to know the history of private market liquidity, the ways that being privately-traded can and will change how companies operate, and how the public markets failed.

The public markets have lost product-market fit

The original proposition behind going public was that in exchange for disclosing information about how their business operates, companies could raise directly from retail investors–giving them access to a much larger pool of capital.

But conditions in the public and private markets have changed substantially, and the idea of going public has become far less appealing for many entrepreneurs over the last two decades.

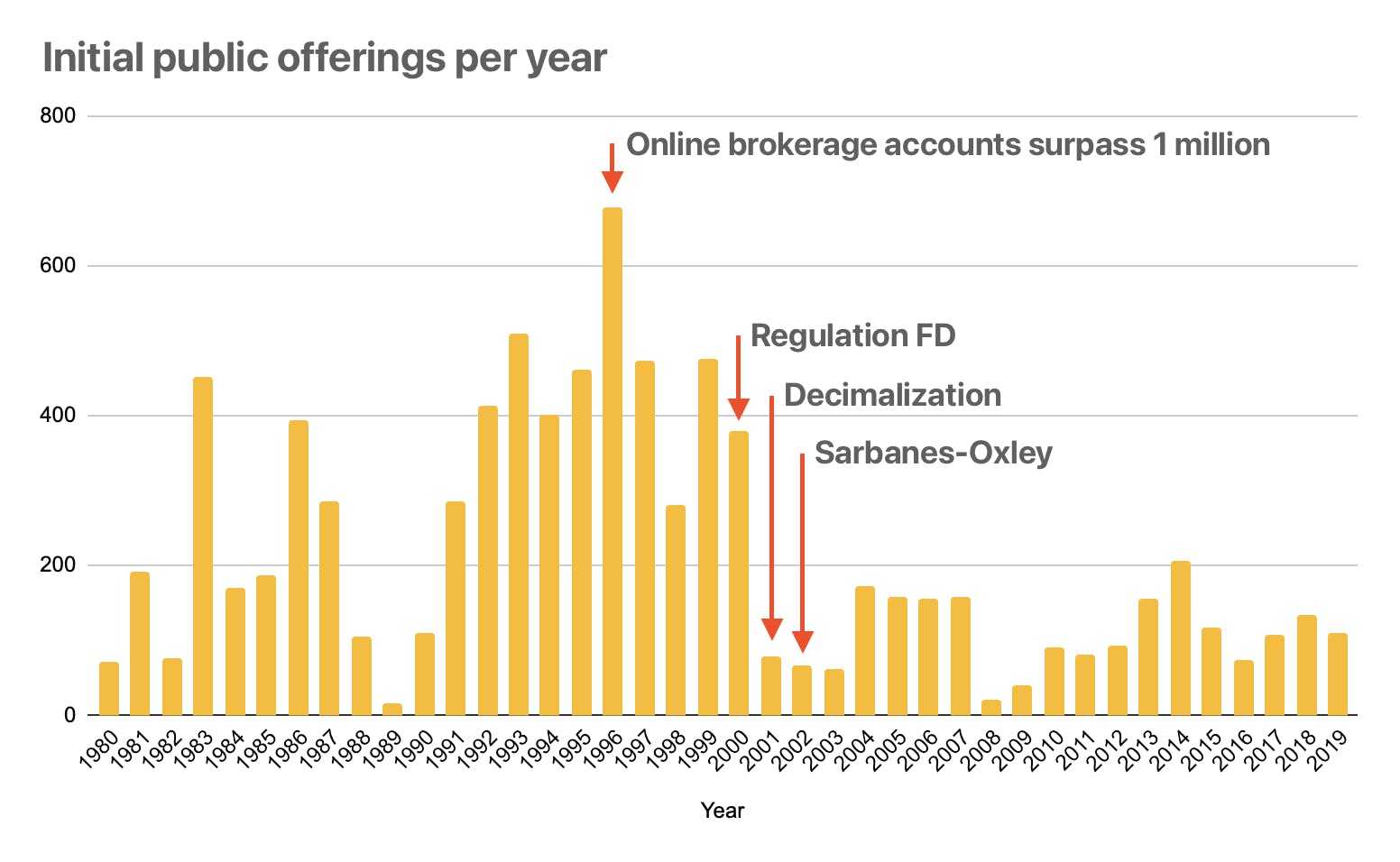

At the end of 2019, there were 3,473 stocks listed on U.S. stock exchanges. That’s down more than half from 1996, when there were 8,025.

The median companies that do go public are taking nearly three times as long to do so: 10 years (across all VC and buyout-backed companies) up to 11.5 years (for technology companies), compared to just 4 years in 2000.

There is no shortage of companies being built. The total AUM of American buyout funds has risen by more than 4x over the last twenty years to more than $1.4 trillion. VC AUM has risen from $150 billion to more than $450 billion.

The problem is that the public markets are increasingly for big, already-mature companies––not for young, fast-growing ones.

Many of the traditional rationales for going public have been eroded. Today, companies need to evaluate whether the benefits––access to certain capital markets and increased accountability––are worth the trade-offs, like short-termism and incentive misalignment.

When asked about the prospect of an IPO, Blue Bottle Coffee founder James Freeman said that given “everything [he’d] seen and read, it seems like a way of living in hell without dying.”

For Michael Fleisher, the CFO of Wayfair, going public is the last thing a private company should think about doing. “If you can continue to raise money privately, and there is sufficient liquidity for you and your current investors, don't go public,” he told Inc.

Snap CEO Evan Spiegel had an even simpler message. “Don’t go public,” he told founders considering an IPO at a Goldman Sachs investor conference––and this was after $SNAP had tripled from its 2019 lows.

Today, going public and being a publicly-traded company have simply become much less appealing for many entrepreneurs––something that they are forced to do for liquidity rather than the dominant win condition of building a successful business.

Behind the rise of direct listings, SPACs, and dual-class share structures is the fact that companies are doing everything they can to “hack” the traditional public offering.

Companies aren’t eager to go public anymore, and understanding why they’re hacking the system to get what they want helps clarify what’s wrong.

There are three core "product" problems in the public markets:

- Overbundling: The public markets promise the ability to raise capital, get new investors interested in your business, and provide shareholders with liquidity--but most companies only really need one out of three of those

- Cumbersome customer experience: Going public is time-consuming, legally risky, and not set up well to help companies tell their story to the public or to investors

- Wrong customers: The public markets offer companies access to a whole swath of new potential shareholders, but in most cases, they’re not the kind that companies want or need during their current stage

Over-bundling

The public markets’ product is a bundle. When you go public, you get access to capital, you get liquidity, you get a bank to help tell your story to investors, and you get a shot of prestige.

But the cost of this bundle has risen substantially since the late 1990s. IPOs started to become substantially more expensive during the dot-com era with the passing of Regulation ATS and the overturning of Glass-Steagall.

Sarbanes-Oxley and other rules passed in response to the collapse of Enron and Worldcom further increased the cost of going public by about 90 basis points, or $5 million given 2019’s average deal size of $546 million—that’s in addition to the $1 million+ companies pay yearly to stay in compliance.

While not directly quantifiable, Sarbanes-Oxley also forces managers of public companies to divert substantial amounts of time to compliance related tasks and has made legally much riskier to become a director of a public company.

Sarbanes-Oxley was one factor that influenced the rate of IPOs falling around the turn of the millennium, but it was not the only one.

All these fees together—for legal advice, audits, consulting, and other regulation-related preparation and maintenance—disproportionately hurt smaller companies and significantly raise the bar for going public.

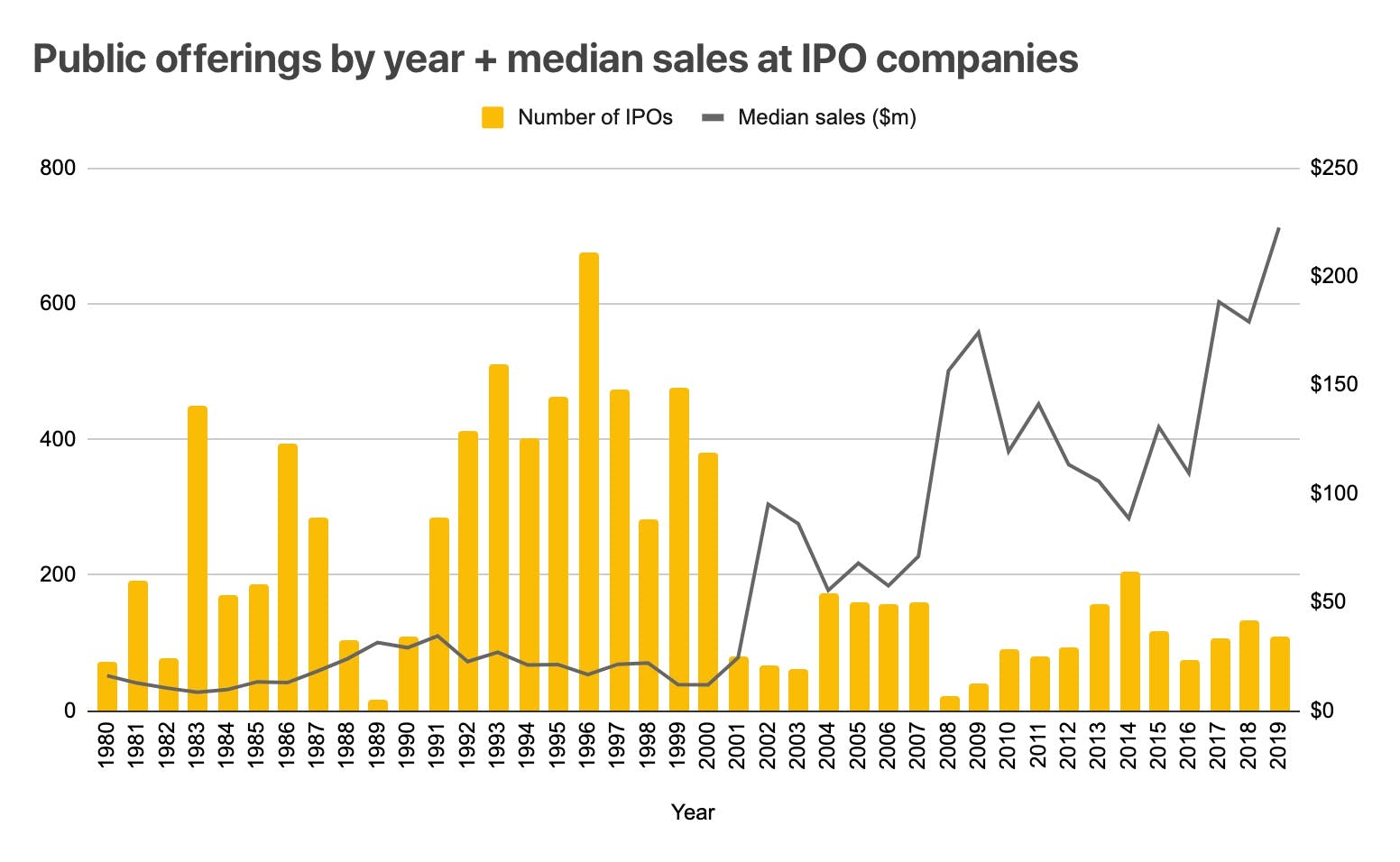

As the number of IPOs per year fell fast off dot-com highs, expectations for new offerings also rose, with median sales across IPO companies rising from barely $25 million a year through the first years of the decade to more than $200 million a year today.

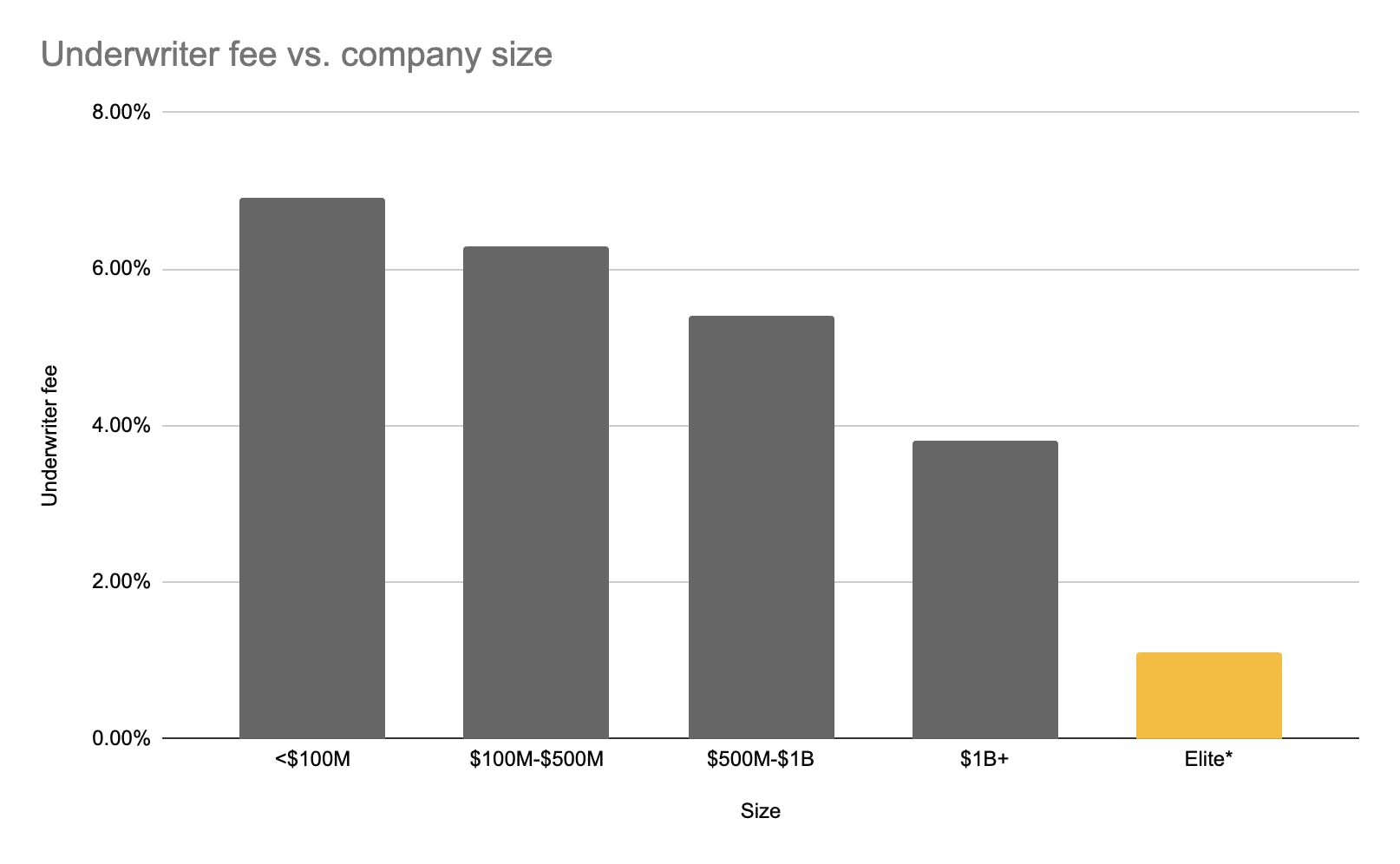

Smaller companies are further disincentivized from going public by the fact that IPO underwriters charge higher fees for them—up to 7%, compared to under 4% for companies over $1 billion and even lower than that for prestigious pre-IPO companies like Facebook and Twitter. This “middle-market” tax can mean that small to midsize companies must pay millions more to go public.

The IPO process is tilted in favor of big companies, which can negotiate underwriter fees far smaller than the 6-7% that is typically charged to smaller companies.

As a result, going public has increasingly become a viable goal only for the biggest companies.

Direct listings

A direct listing allows companies to go public without raising primary capital, working with an investment bank underwriter, or dealing with six months of lock-up restrictions on insider stock sales. Instead, companies can simply begin allowing their shares to trade and let the market set a price.

Spotify likely saved at least $90 million going public through direct listing in 2018, cutting a range of costs from the pre-IPO roadshow ($100,000~) to the underwriter fee (1-7% of all capital raised).

In total, they paid about $45 million to go public, while Facebook (about three times their size) paid $176 million, and Snap (about half their size) paid $85 million—if we take the average of those two outcomes, we can estimate Spotify would have paid about $130 million. While 3.5% to 7% is the traditional investment banker cut, big companies like Spotify can negotiate their rate down.

Currently, only secondary sales of stock are permitted during a direct listing (direct listing companies cannot raise primary capital), though the NYSE and Nasdaq both are working on changing that.

Cumbersome customer experience

"[On] July 13, 2017, there was still tremendous uncertainty as to whether the Company would complete an IPO in 2017, in 2018 or beyond." —MongoDB SEC filing from October 2017 (a month after the company went public)

Going public is often a highly uncertain moment in a company's history. Forecasting is critical for executing a successful IPO, and it’s difficult for many still-growing private companies to know what their financial results will look like in the quarters after their listing, much less what they'll look like years out.

It’s also impossible to predict what the broader market will do, and between filing to go public and listing, anything can happen.

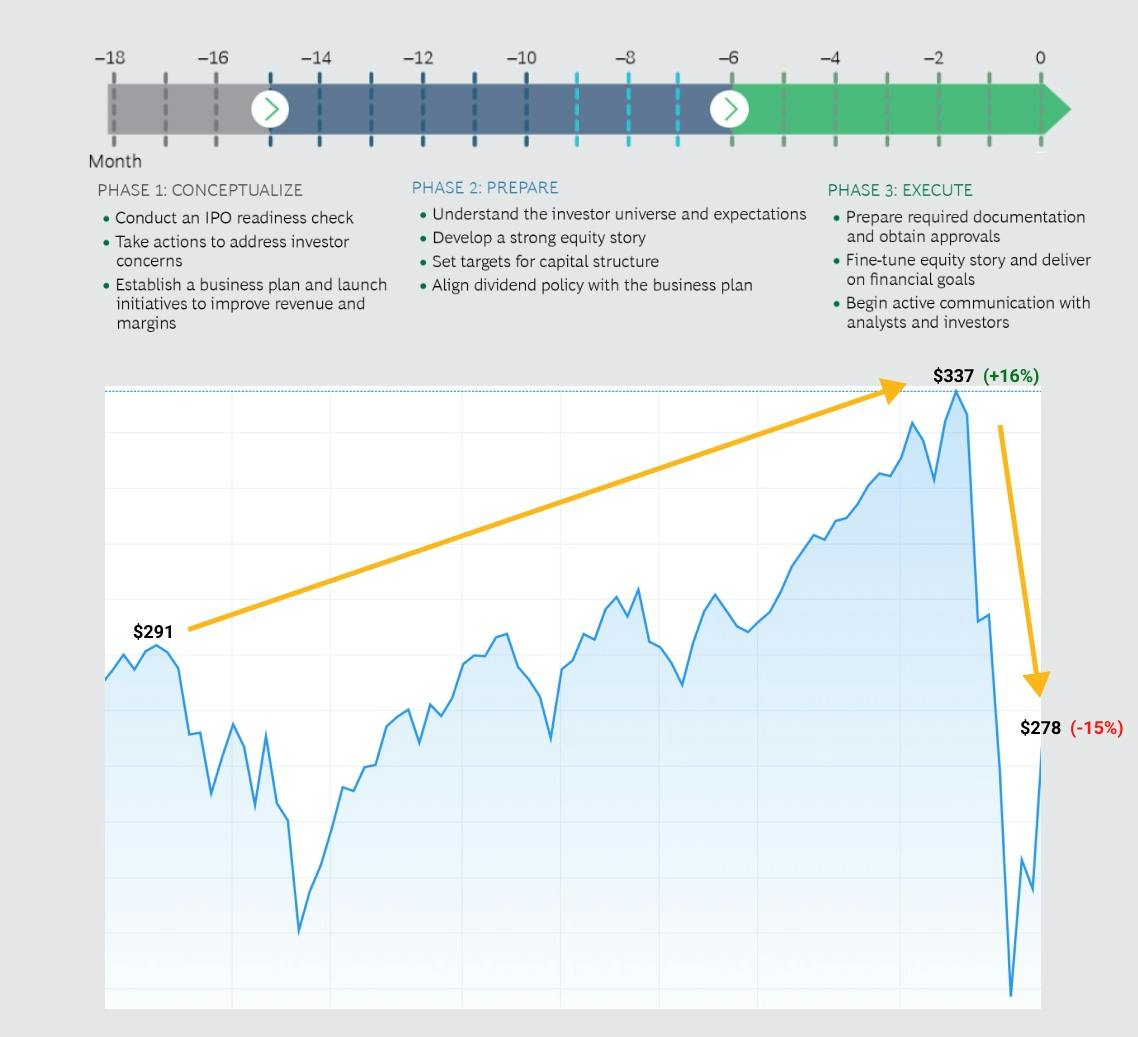

The typical IPO timeline, from conception to execution, is about eighteen months––in the markets, enough time for everything to change.

In many cases, the public markets have not been kind to private companies with high valuations.

Casper ended its first day of trading with a market capitalization of $535 million—less than half of the $1.1 billion valuation it received in the private markets.

Blue Apron, which was once valued at $2 billion in the private markets and went public at $1.9, was worth less than $1 billion just a month later.

Two years later, it was worth less than $100 million.

SPACs

The SPAC (special purpose acquisition company) is a vehicle that can help companies mitigate these kinds of uncertainties when going public. While SPACs made up just 10% of IPOs between 2003 and 2015, they accounted for 31% during the GFC in 2008 and 2009.

While SPAC IPOs have taken place for decades, they’ve become more popular in recent years. In a SPAC IPO, the entire transaction can be “pre-baked” with SEC approval and you can go public within 90 days. Instead of hoping the IPO window stays open while you wait, you can make a much more aggressive entry into the market.

You can spend time with Wall Street and create forecasts (which you can’t do when you go public via IPO), meaning you’re more likely to get analyst coverage, which tends to increase a company’s stock price while reducing volatility.

Lastly, you have the freedom to raise as much capital as you want, doing any mixture of primary/secondary fundraising, and you can remove all lockups on founders and employees so they can get liquidity immediately.

Wrong customers

Going public means swapping out one set of “customers” for another.

A company’s first customers—the VCs who invest early on—are closely aligned with management and are directly incentivized to help the company succeed and build value over the long-term.

When companies go public, these early adopters are replaced with late adopters—hedge funds, mutual funds, retail investors and others.

Like late adopters of any product, they will have varied motivations and incentives. Many are not in it for the long-term—many will be more concerned with hitting quarterly earnings goals. And that can exert the wrong kind of pressure on management.

Dual-class shares

Dual-class shares allow founders and executives to insulate themselves to a degree from short-term pressures in the market, in theory permitting them to remain innovative like a private company while being publicly-traded.

Research has shown that this is an effective technique, with dual-class share companies exhibiting:

- fewer transient institutional holdings (less short-termist investors)

- lower amounts of analyst coverage (too much of which can exert a chilling effect on innovation)

- a higher output of creative patents

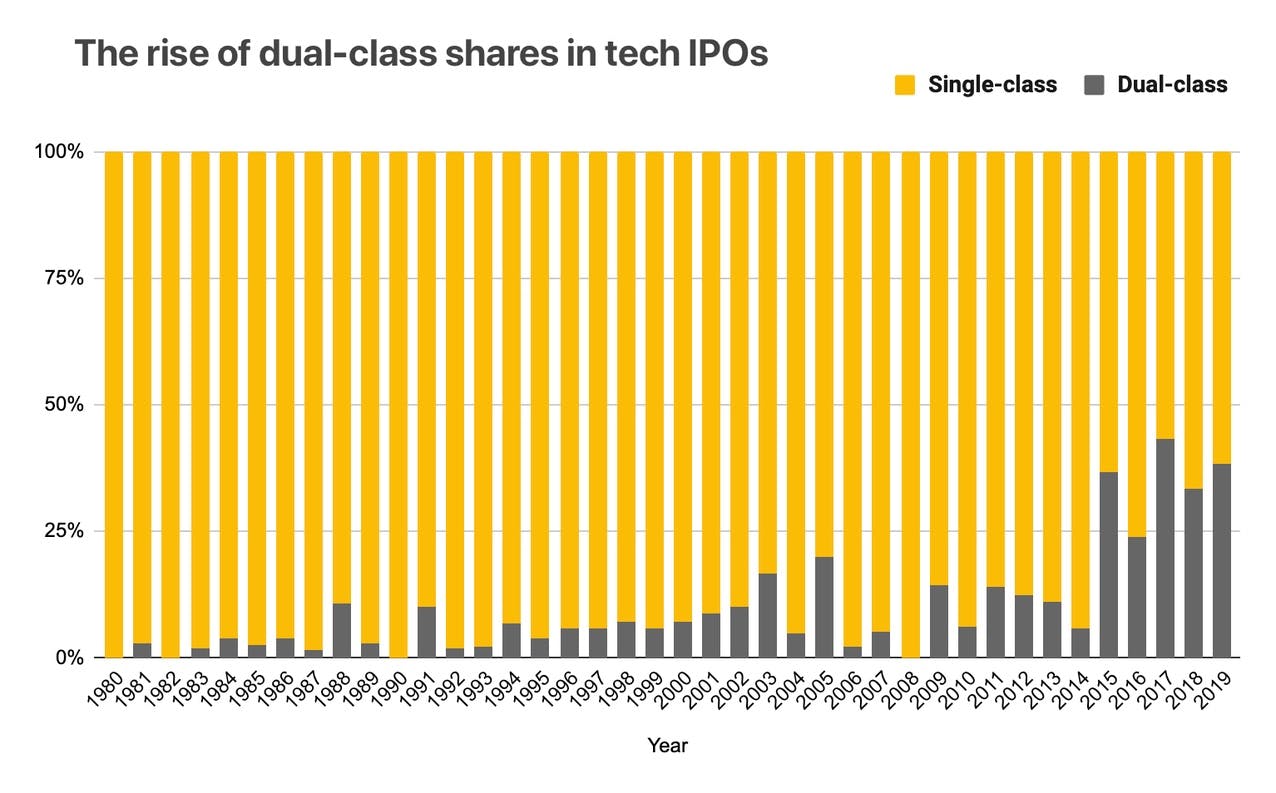

Since 2008, there has been a resurgence of interest in dual-class share structures, particularly among tech companies going public. The percentage of tech companies using dual-class share structures at IPO rose from 0% in 2008 to 14.3% a year later to 36.8% in 2015.

Around a third of tech companies go public with dual-class shares–a structure that was a rarity even during the halcyon days of the dot-com boom.

In 2017, 25 percent of IPOs across the board had dual-class shares—Snap, Blue Apron, Roku, and Stitch Fix among them—up from just 1 percent in 2005.

Those dual-class IPOs also outperformed all other IPOs in 2017 by about 500 basis points, and evidence suggests dual-class share structures do increase the value of high-growth companies—even if that value lessens over time. Additionally, companies with dual-class shares exhibit higher sales growth and more R&D intensity.

The data suggests that there’s benefits both for companies and shareholders in allowing public companies to behave more like private companies.

Disruption from below: the privately-traded company

Because the public markets have become increasingly inhospitable, more and more private companies are opting to stay private longer.

As a result, there are now more than 220 US-based unicorn companies. There were only 10 a decade ago.

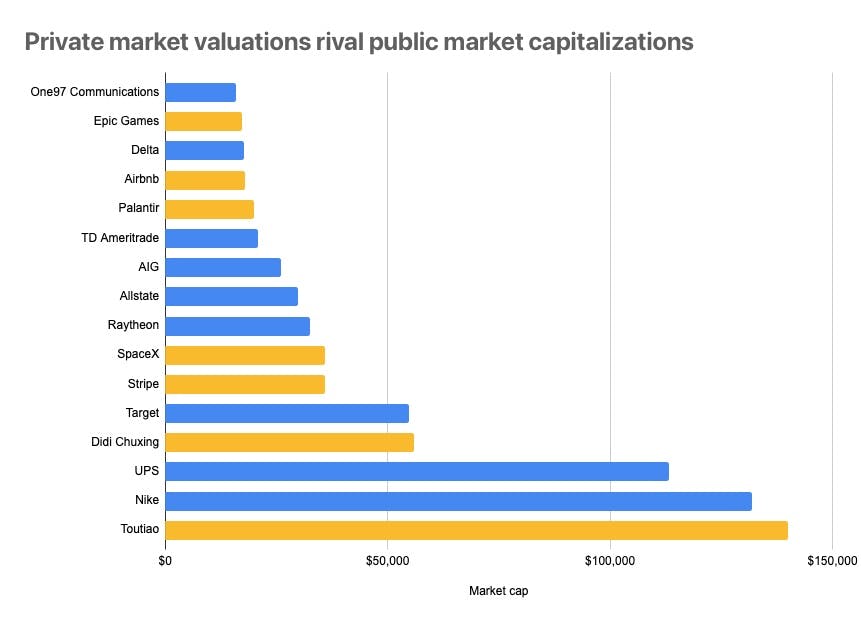

Many private companies today look like public companies in terms of both size and relevance.

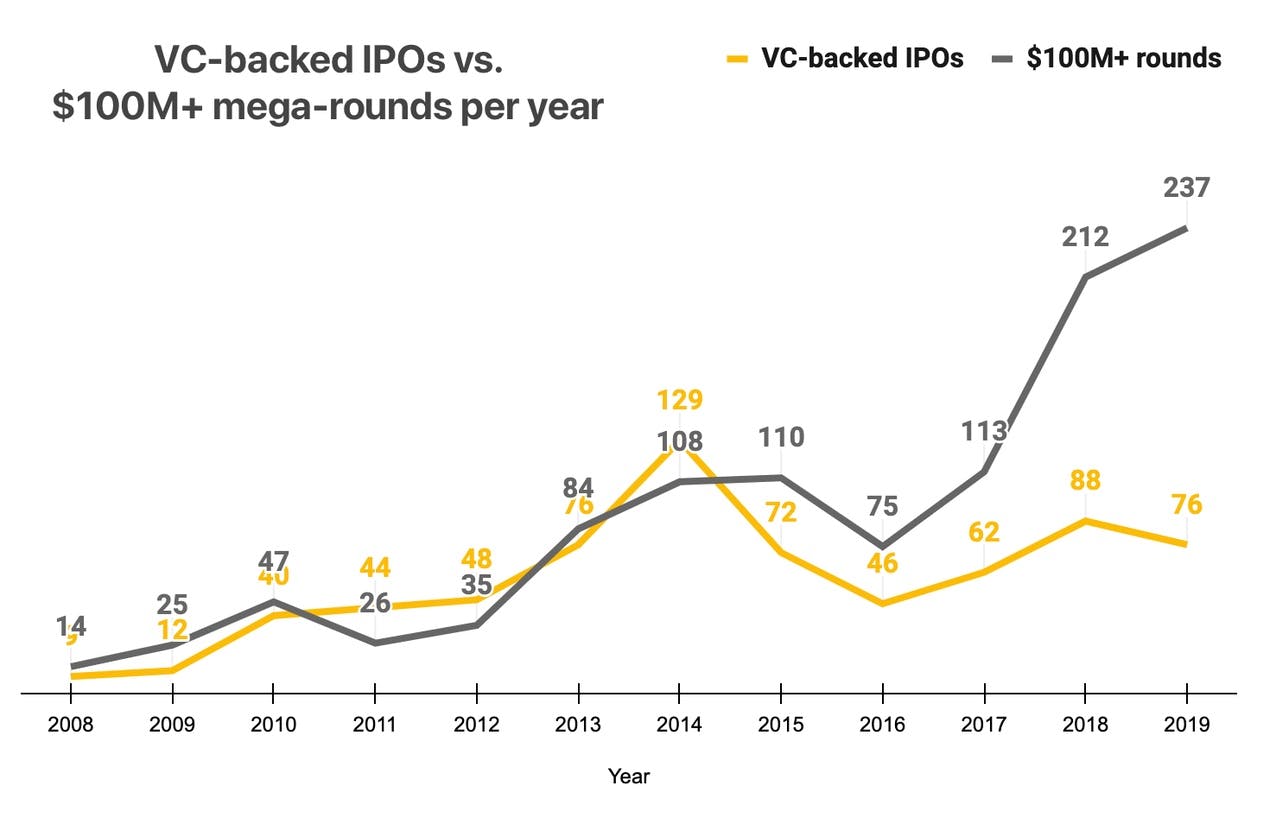

In 2019, there were 237 private fundraising rounds of $100 million or greater—approximately the median IPO deal size. In contrast, there were just 76 VC-backed IPOs.

Since 2016, the numbers of VC-backed IPOs per year and $100 million or more "mega-rounds" have diverged, with the so-called "private IPO" becoming 3x as common as the VC-backed IPO.

But while staying private for longer has become more viable each year with the continuing influx of money into venture, late-stage private companies face big challenges at scale.

On one hand, their cap tables become more and more complex, with no-longer-aligned ex-employees and early investors taking up valuable space that could be used to bring on new, strategic shareholders.

On the other, without liquidity, no one––from employees to investors to M&A targets––can get a real sense of what their stock is worth. That makes it difficult to recruit, to make acquisitions, and ultimately, to transition to the public markets.

Ultimately, for many companies, the lack of liquidity that comes along with being private becomes an existential threat. Companies must go public not just to keep their talent happy (instead of decamping for a public company with a high-compensating ESOP), but to make strategic acquisitions, bring on new investors with long-term time horizons, and extend their runway.

These twin problems of misalignment and price discovery are closely correlated. But with the ability to float some of their shares on the private markets, companies get a powerful set of tools to address both.

Restore alignment by refreshing the cap table with secondary sales

Cap table misalignment is one of the biggest problems that companies face as they scale through round after round of primary fundraising.

With each new fundraise comes a new batch of investors onto the cap table, often creating a Hotel California effect: shareholders can check out, but they never leave.

This disproportionately affects early employees and early investors. By those later rounds of funding, many of those shareholders have already left the company or dropped out of touch, their talents vastly better suited to growing and building something new (hence why they joined early) rather than scaling something into a multi-billion dollar machine.

The problem for companies is that, as they get to be worth around $500 million to $1 billion, they also find that the preference stack on their cap table has grown into the $50 to $100 million range. Huge portions of that stack are made up of those early investors and early employees who are no longer aligned with the future of the business.

To bring on the new strategic investors they need to grow––whether it’s later-stage funds with experience scaling companies or crossover funds who can help them go public––they end up needlessly creating new shares and dilute all the existing investors on the cap table.

It’s particularly needless because plenty of those early investors and ex-employees would be eager to sell their equity and free up that spot on the cap table.

Privately-traded companies can use secondary sales to refresh their cap tables, cashing out early investors and bringing on new, strategic ones––without the dilution of a primary.

If issuers allow those stakes to be sold to those new strategic investors, it allows them to put together a cap table that’s more aligned for the long-term future of the company without the dilution of issuing new shares.

Secondary sales designed to cash out early shareholders can be run on their own or in conjunction with a primary, which makes it a flexible tool for CFOs trying to be strategic about how they use the limited space on their cap tables.

Lower cost of capital and reduce dilution by changing out investors

More investors having access to private companies via secondary sales means a lower cost of capital for startups and less dilution.

Companies can raise huge amounts of capital from the kinds of late-stage investors getting involved in venture today, and they can give up relatively little in return because their structure and incentives are different.

Traditional venture firms need to cover their 2 & 20 plus hit a 20-25% IRR on a strict 10-12 year cycle. SoftBank’s Vision Fund, on the other hand, charges a management fee of just 1%, with 20% carry only on gains beyond 8%.

The same goes for investment banks, hedge funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds, and other institutional investors––with different structure comes a different cost of capital.

Liquid secondary markets will bring down that cost of capital down even further, making it even more attractive for late-stage companies to stay in the private markets––and further benefiting these deep-pocketed institutional investors.

The basic reason liquidity begets a lower cost of capital is its impact on risk. When LPs have less liquidity risk, they can require a lower liquidity premium of their GPs. That means GPs can raise more and require lower minimum returns from their companies. If a VC knows their portfolio companies are guaranteed to have liquidity in 2-3 years, then they don't need as much ownership, nor do they need to rely on 1,000x opportunities to return the fund.

Vision Fund and other non-venture investors enjoy the benefit of this too. They can pick up secondaries at a discount, and in a more open, liquid secondaries marketplace, can do so without being as limited to deals where they have insider access.

Secure in the knowledge that they’ll be able to sell on those same secondary markets, it’s likely we’ll see institutional investors increasingly investing in seed and Series A rounds––both to reduce their reliance on VC funds and to acquire a position from which to easily scoop up secondaries later.

Deep-pocketed investors with lower cost of capital and lower return requirements playing in seed and Series A/B markets could pose a significant challenge for traditional VC firms. The biggest VC firms extract discounts from their portfolio companies on the basis that their involvement in the company will help them raise money later.

The networks and expertise that GPs bring to the table are certainly important for companies. But whether even the biggest VC firms will be able to maintain that 10-14% “de-risking” discount remains an open question when sovereign wealth funds and massive asset managers, who can quite easily finance a company all the way from seed through IPO on their own, begin competing with them on a more level playing field.

Price stock more accurately to enable competitive recruiting and a more stable business

Allowing some portion of shares to trade privately, even if only within a market of 100~ investors or so, is a hugely powerful tool for issuers because it enables price discovery.

Price discovery is one of the central tenets of the public markets. Aggregate the buyers and sellers of an asset, and you get to ground truth on its value fast.

In the private markets, on the other hand, companies are valued based on negotiation between the issuer of shares and the lead investor in their round.

This creates two big problems.

For employees, in many instances, it becomes very challenging to get liquidity––a constraint that can make it impossible to handle major life events like buying a new home or taking care of a sick family member. This increases churn and makes recruiting harder.

For companies, it makes it increasingly difficult to flip the switch to operating as a public company. Stay private too long, and the economics of venture (and those “negotiations” over valuation) mean that your share price tends to explode and make it hard to justify your IPO.

With a more liquid market for their stock, however, companies can begin the process of getting real price discovery earlier––and in doing so, recruit and retain the best talent while smoothing out their evolution into a more mature, disciplined company.

Provide “off-balance sheet bonuses” with a recurring liquidity program

For years, the conventional wisdom on employee liquidity was that it was dangerous for retention to allow employees to “cash out” early.

What has emerged in the absence of private liquidity, however, is an even more deleterious style of option-optimized job-hopping.

Since employees know they’re unlikely to see liquidity at any of the early-stage companies they join, they hop from startup to startup, never staying longer than four years––and most often, leaving as soon as they think they’ve spotted the next unicorn.

Building a great business becomes much more difficult when you have your employee base churning over on this tight of a schedule.

A common argument against employee liquidity is that the equity the best companies already give their employees is valuable enough––but in reality, it is the biggest, fastest-growing private companies today that are inventing the future of private liquidity.

One of the best ways to get the best talent to come to your company and stick around is to offer not just a growing valuation and high growth rate, but liquidity to go along with it.

Liquidity can commit employees for the long-term in the same way that a small amount of liquidity can de-risk a founder’s investment and allow them to focus on the long-term.

It can also simply make a company’s compensation package so competitive that it begins to look as good, if not better than the package that a hire might get from a public company like Facebook or Google.

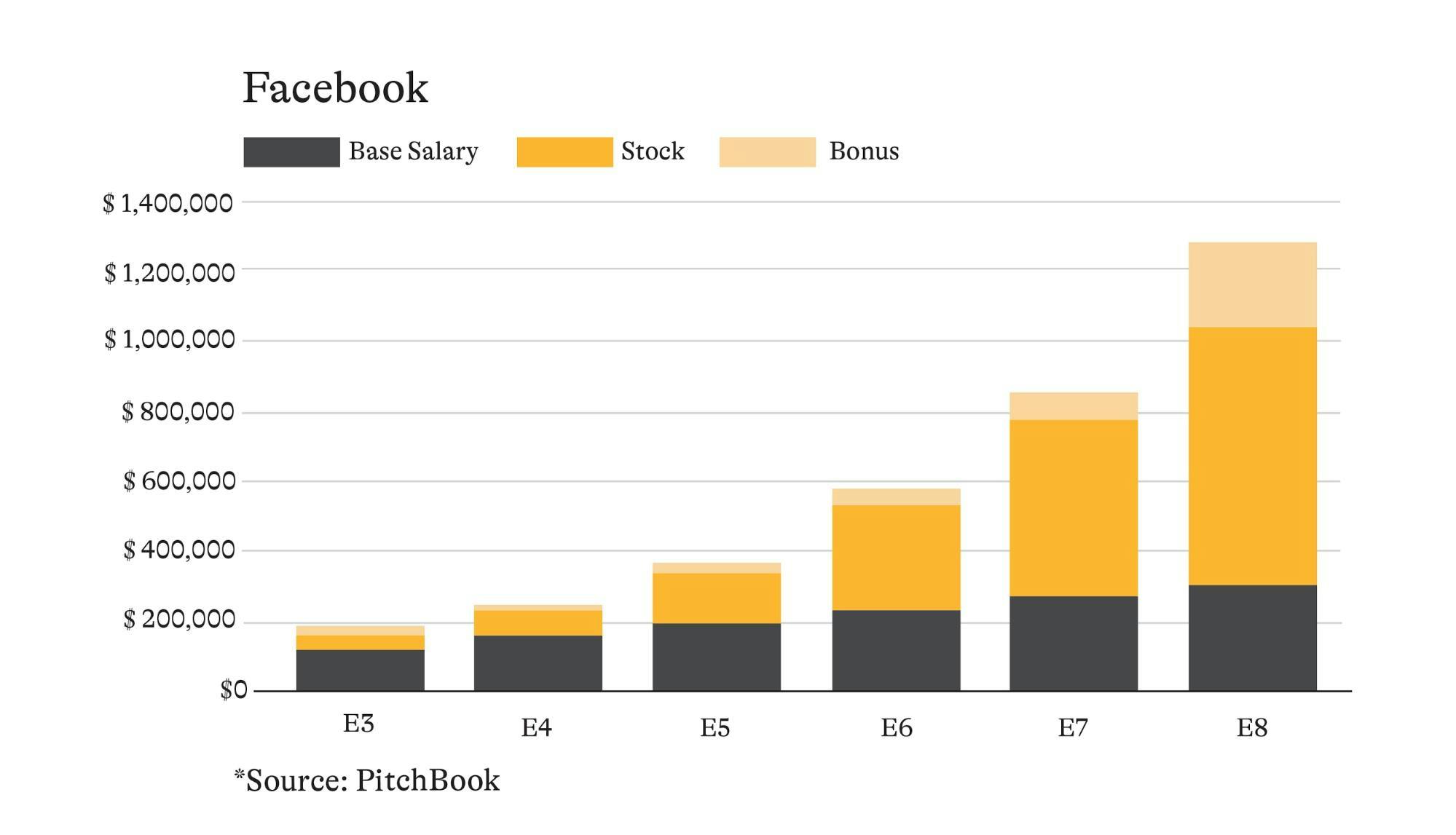

At E4, a Facebook engineer will make well over $200,000 a year, while the typical entry-level or early startup engineer makes around $120,000 a year.

Public tech companies can offer outsized salaries not because they're willing to throw heaps of cash at their employees, but because they have highly valuable, liquid equity that they can offer.

But private companies have one major advantage over public companies––a steeper growth trajectory.

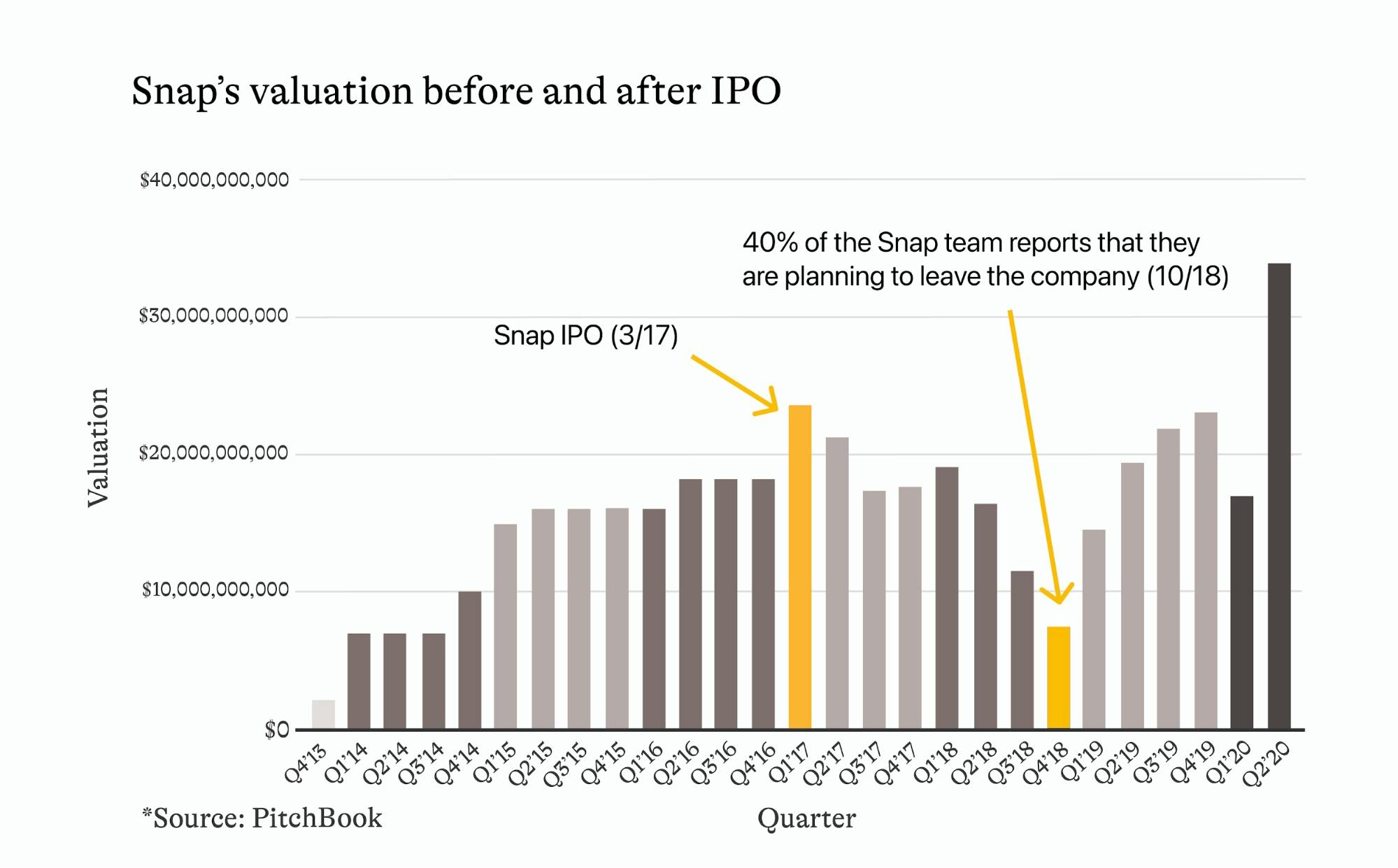

In 2012, Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy incorporated Snapchat. A year later, their company was valued at $70 million. After another two years, it was worth $10 billion. In 2017, Snapchat went public at $23 billion valuation––and then spent two years trading below that price.

Private market valuations don't always translate into the public markets––it took Snapchat two years to justify, to public investors, the price it last raised at in the private markets.

Not all companies are Snapchat, but this is what startups promise: the potential for a fast growth trajectory and the value that such a trajectory can create.

Secondaries allow companies to leverage their growth trajectory to give “off-balance sheet bonuses” that grow incrementally over time and can make working at a startup comparable or even better than a public company from a compensation perspective.

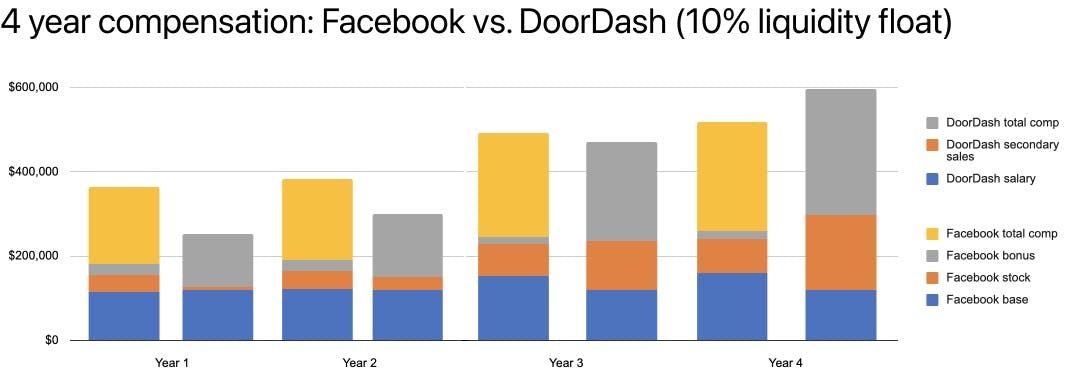

Take an engineer hired by DoorDash as a senior engineer right around the time of their Series C in 2016. As part of their compensation package, they receive 10,000 RSUs vesting over 4 years of which they’re allowed to sell 10% each year.

Over the ensuing four years, Doordash's valuation rises from $23.94 to $229.53, and the cash value of that 10% rises accordingly.

- Year 1: $5,400

- Year 2: $29,900

- Year 3: $115,200

- Year 4: $175,000

Selling 10% each year would result in that engineer receiving total cumulative compensation of $800,000 after 4 years, compared to just $480,000 without any secondary sales (assuming a base salary of $120,000).

With the ability to float just 10% of their shares in the private markets every year, an employee who joins DoorDash at the Series C with a compensation package of 10,000 RSUs can easily earn more than they would at Facebook.

Not only has that engineer brought their total compensation approximately in line with what they would have made joining Facebook (about $870,000 assuming a graduation from E3 to E4), but they would still have a substantial amount of upside left.

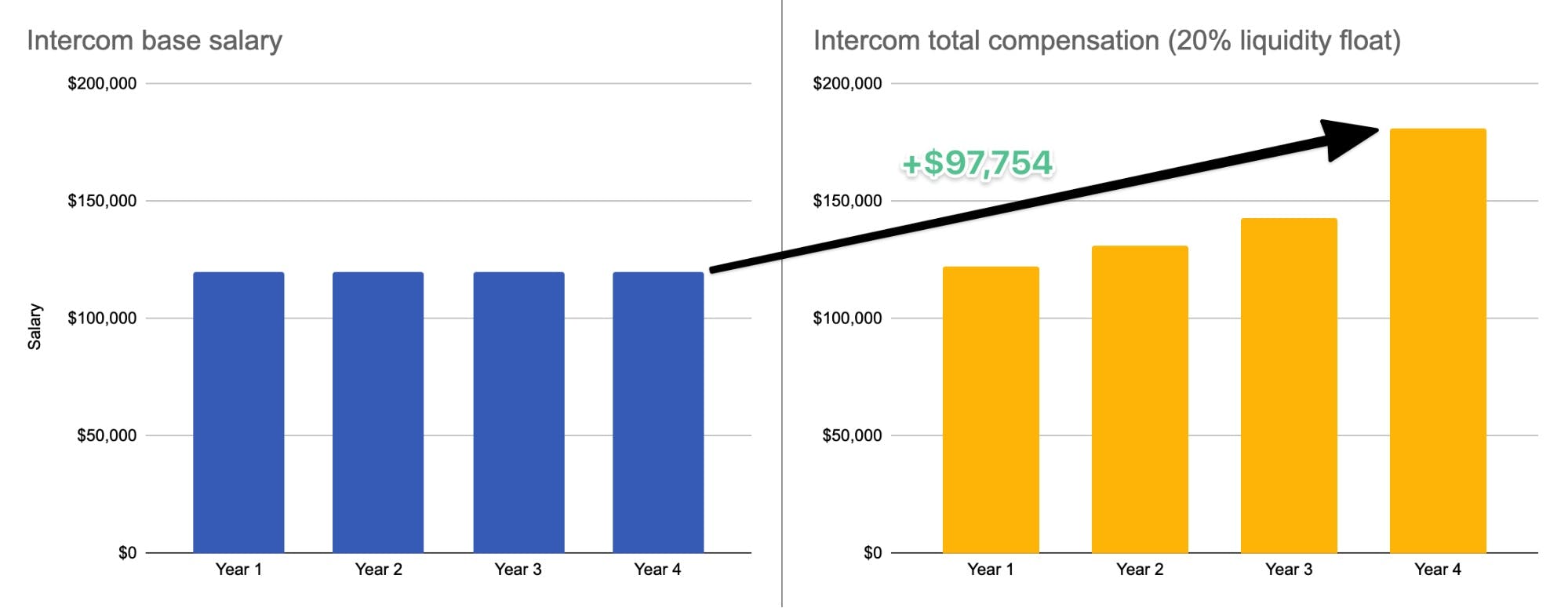

Secondary sales can make for a healthy bonus even at non-decacorns. At the $1.2 billion Intercom, 4 years of secondary sales with a 20% liquidity float would have netted the average engineer who joined the company at Series B (with a base salary of $120,000 a year + 10,000 RSUs) an extra $97,754.

You don't need a skyhigh valuation to give employees meaningful bonuses through secondary sales: with Intercom's $1.2 billion valuation, yearly secondary sales with a 20% float could allow a Series B hire with 10,000 RSUs to earn an extra $100,000 over their first four years.

Even after taking those bonuses, of course, employees are still holding onto the vast majority of their stock. Now, however, they’ve been able to feel the value that they’ve helped create––and they know that if they continue to help the company grow, those liquid shares will be worth even more in the future.

Contrast this to what happens today in the private markets. Employees come to companies that offer equity as a substantive portion of their compensation and then don’t go public. Because there’s no option to gradually de-risk by selling shares, and existing marketplaces for secondary stock are relatively shallow, liquidity becomes binary––either hold 100% or sell 100%. That employees sells their shares off to a fund or commits them via forward contract, and now two things have happened: 1) a party that the issuer doesn’t know is on their cap table, and 2) their employee is completely out of alignment with the company.

Or, assume a company does give its employees the opportunity to participate in a tender offer once every few years. Because those employees assume this one offer might be their only shot to sell, they wind up setting aggressive price targets designed to maximize their earnings and end up disappointed––or they sell low, which undervalues your stock and can trigger other employees to lower their price target as well.

With a recurring program of liquidity and the constant price discovery it brings, issuers can build a program that works to the advantage of them and their employees. For them, it can be a tool for recruiting and retaining the best talent. For their employees, it’s a way to get liquidity gradually and optimize for earnings over time––not try and fail to maximize earnings on a single transaction.

Ease the transition to a public company with regular, structured secondary sales

Companies that build a marketplace for their own stock and allow themselves to be priced by the market more frequently have more control of their own destiny.

When your stock is only priced through private rounds of fundraising that happen every year or two, it can be very challenging to convince a crossover fund, institutional investor, or acquisition target of what you think you’re worth.

If your stock trades quarterly, however, and you have external investors regularly buying in, then you have a functioning market with price discovery––and you have a much stronger argument that you truly know what you’re worth.

Companies raising a new primary round can use the evolution of their share price in the secondary markets as an anchor to begin negotiations.

Companies can raise a round of debt with warrants tied to a price established in the secondary markets last quarter versus a price established in a primary round two years ago, likely lowering their cost of capital substantially.

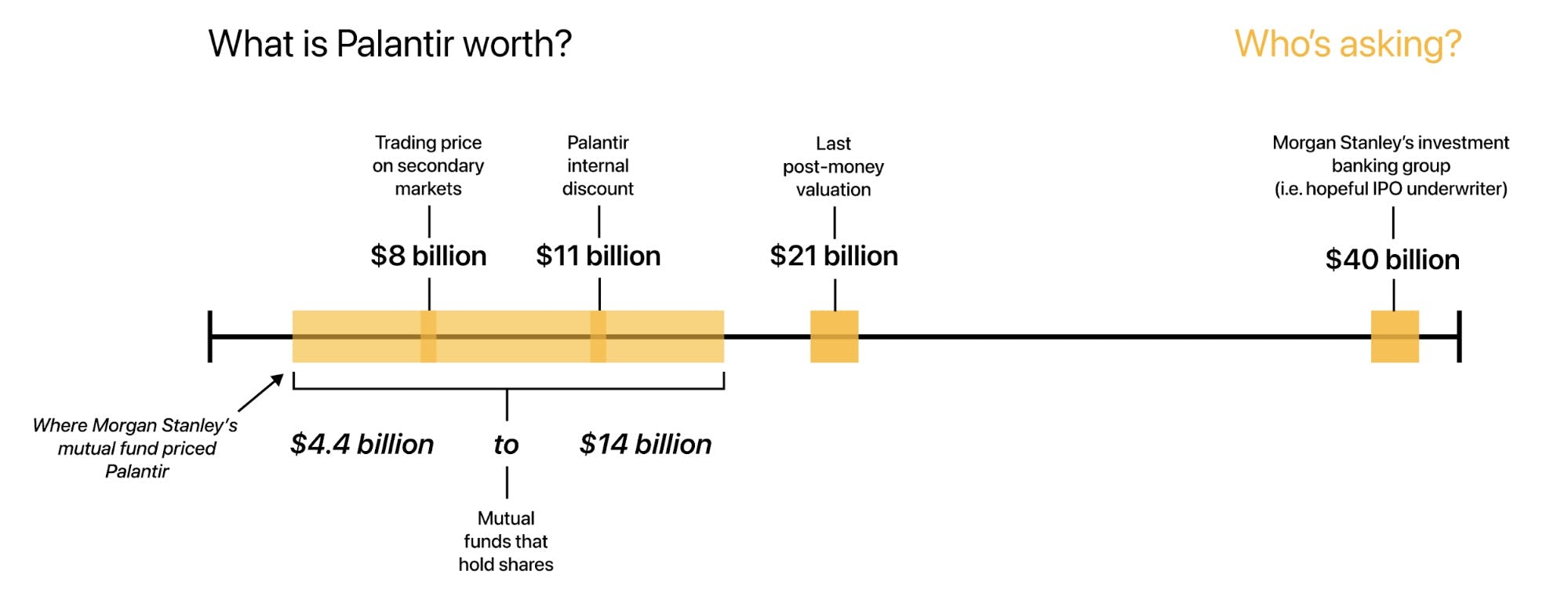

When companies stay private for a long time, valuations from different stakeholders can get out of sync––a problem that can be mitigated with more active price discovery earlier on.

And when and if companies decide to go public, they can use that secondary marketplace they’ve created to skip the process of getting an investment bank to underwrite their shares and use the price discovery they’ve already facilitated to direct list.

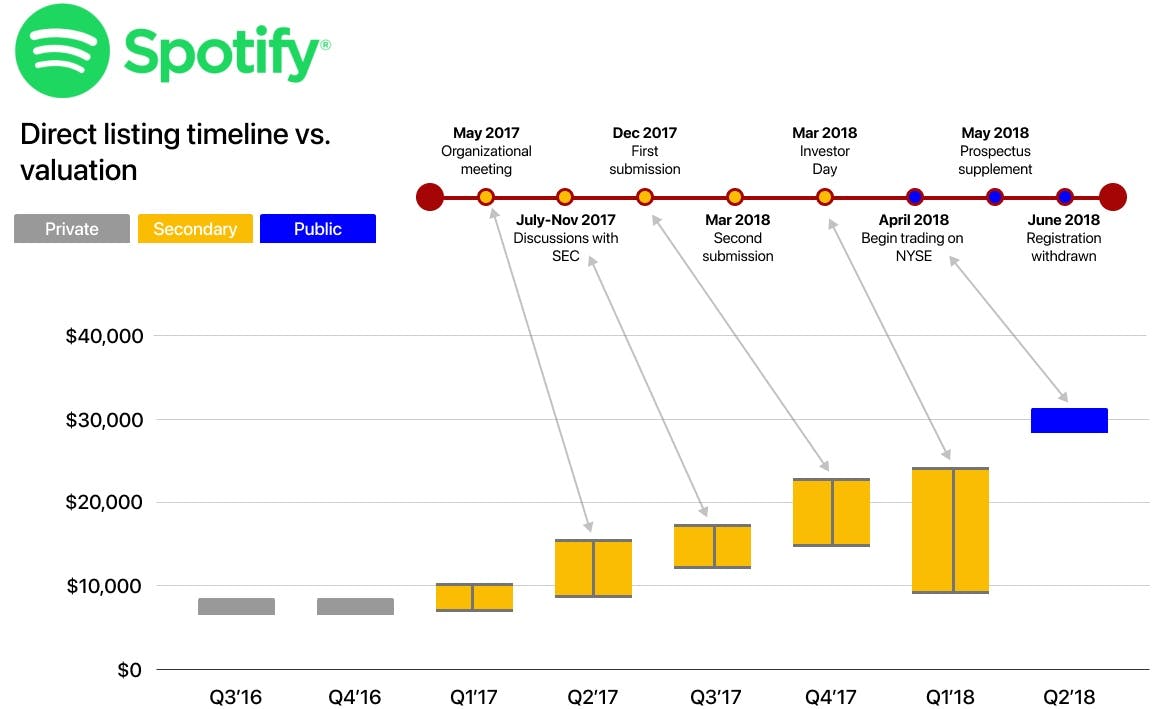

Spotify’s pioneer direct listing in 2018 was a big event in the world of private fundraising, but lesser known is the story of how they got there: through a few years of encouraging this kind of highly active secondary market in their shares.

When companies go public via a direct listing, they don’t get the bookmaking function that investment banks provide. Without a mechanism to determine what investors are willing to pay for a company’s newly floated shares, companies that want to do a direct listing need to show some other form of price discovery.

That’s why Spotify had been preparing for its 2018 direct listing for years, most importantly by running quarterly liquidity events where shares traded openly among a group of employees, investors, and institutions.

In conjunction with these sales, Spotify began acting like a public company in other ways as well, holding quarterly shareholder calls and making regular financial disclosures.

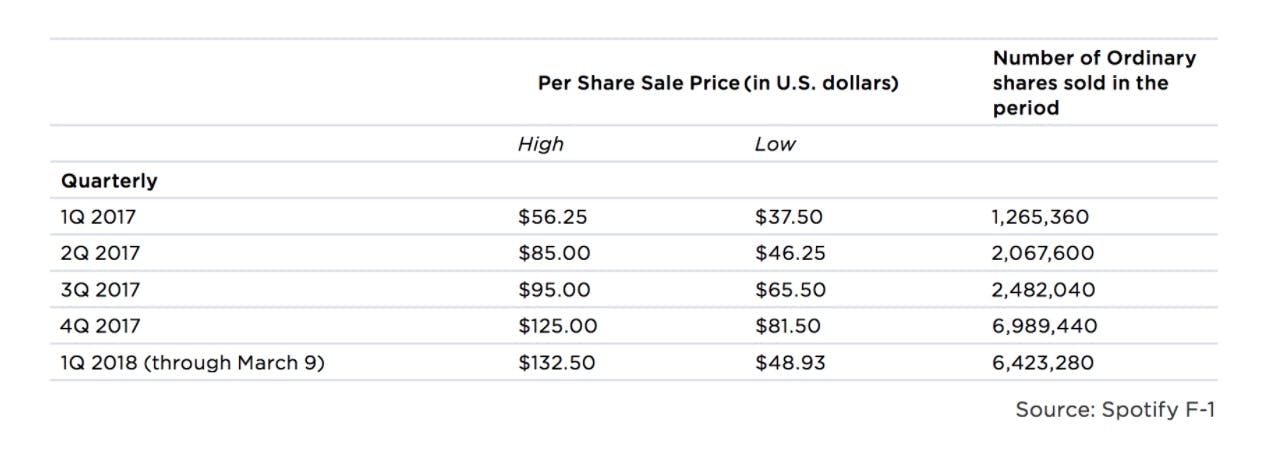

Spotify's shares traded in a gradually growing range of prices between 1Q 2017 and 1Q 2018, and that rise helped justify the eventual reference price under which the company went public on the New York Stock Exchange.

By the time they were going public, Spotify had a precedent for their reference price of $132 through a series of secondary transactions that had taken place at that price. They had experience disclosing information to shareholders and managing their investor relations. And all those secondary sales seemingly soaked up any demand there might have been from investors and employees to sell, too.

At each milestone through the direct listing process, from filing the initial documentation with the SEC to meeting with investors, they were able to point to the highly active secondary market for their shares as proof that their shares were in demand.

For Spotify, opening up a secondary market in their shares was something done in tandem with the process of applying to direct list their stock.

Despite the lack of any lock-up restriction on their stock, Spotify would go on to close its first day of trading significantly up from that reference price––and then continue to rise by more than 40% over its ensuing 4 months in the market.

When many private companies run into problems in the public market because their stock hasn’t been priced by the market before, Spotify took the opposite approach––creating as active a market as possible. That gave early investors and employees a chance to sell, it gave external investors confidence in the company, and ultimately it facilitated a smooth transition to the public markets.

The future of private company liquidity

The era of the privately-traded company is emerging fast. The privately-traded form offers companies massive benefits, and going public continues to be an expensive, onerous exercise.

Unlocking private liquidity represents a massive opportunity given the huge amount of directly addressable value. There is now $1.5 trillion worth of private shares waiting to be unlocked on the cap tables of the world’s venture-backed startups––and that figure has been increasing at more than 46% CAGR for more than two decades.

Only $30 billion of that is currently being transacted each year, or 2%. A decade ago, that figure was closer to a few billion total.

In the years to come, we expect to see that percentage continue to increase as macro factors force companies to stay private longer and extend more liquidity to shareholders and as various liquidity solution providers develop better offerings.

The coming liquidity crunch in late-stage privates

None of the trends propelling the growth of the private company liquidity industry are slowing down––in fact, startup employees and investors are being squeezed for liquidity harder and harder with each passing year.

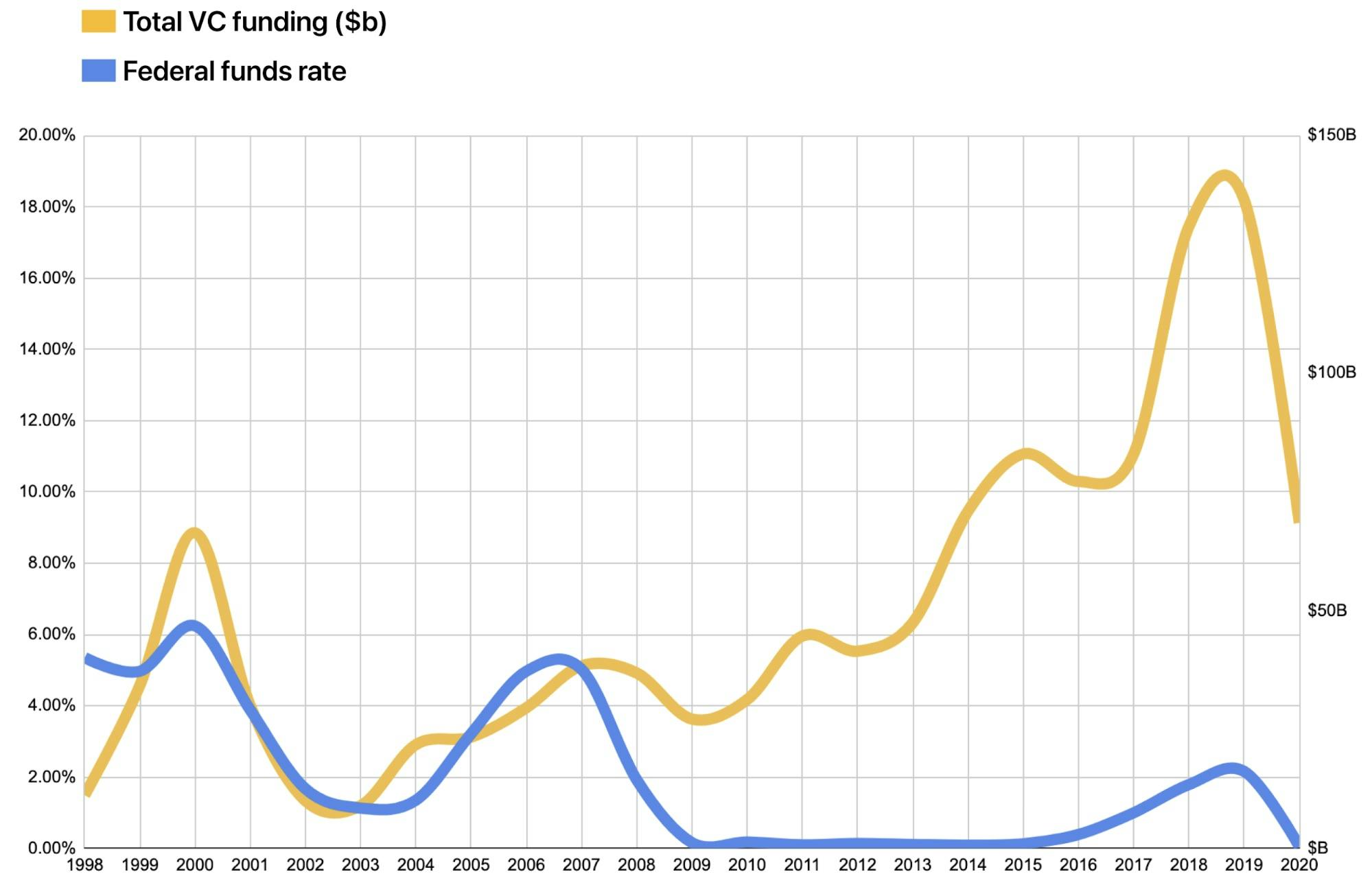

The Fed cutting interest rates to near zero in 2009 triggered VC funding to rise from $27 billion to $136 billion a year, and the Fed is now expected to keep rates at zero for the next five years. This will have the effect of both increasing late-stage fundraising further and driving a rise in secondary market transaction volume.

Since 2009, the near-zero federal funds rate has helped fuel an explosion of capital into venture, as more and more investors have sought out yield in the private markets.

Low interest rates cause asset managers, pension funds, endowments and other LPs to allocate more capital to venture. As Sequoia’s Alfred Lin put it, "With interest rates close to zero, you can’t make money in the bond market, so the bond people now invest in stocks, and people who invest in stocks invest in private growth rounds.”

More capital flowing into venture capital means larger funds, and larger funds must write larger checks into larger companies. Low rates also incentivize investors to de-risk, which in this case means allocating more of their money into late-stage companies and less into early-stage bets.

As more capital flows into these big companies, they stay private longer, creating pressure from both investors and employees for liquidity.

When companies stay private for too long without liquidity, employees may leave and it can be challenging to recruit new employees––investors who need to raise a new fund, meanwhile, may have trouble producing the money for a follow-on.

For issuers, orchestrating secondary sales becomes important not just to align with investors and employees, but also to begin the process of price discovery to ease the transition to going public.

Then there are the changing dynamics of the technology market in general. Many of the core technological markets like social networks, smartphones, and ecommerce have begun to reach asymptotes of adoption. As these bigger private companies begin to compete more seriously with one another for growth in a more and more zero-sum world, they will require even more capital and even longer timeframes to achieve their ends.

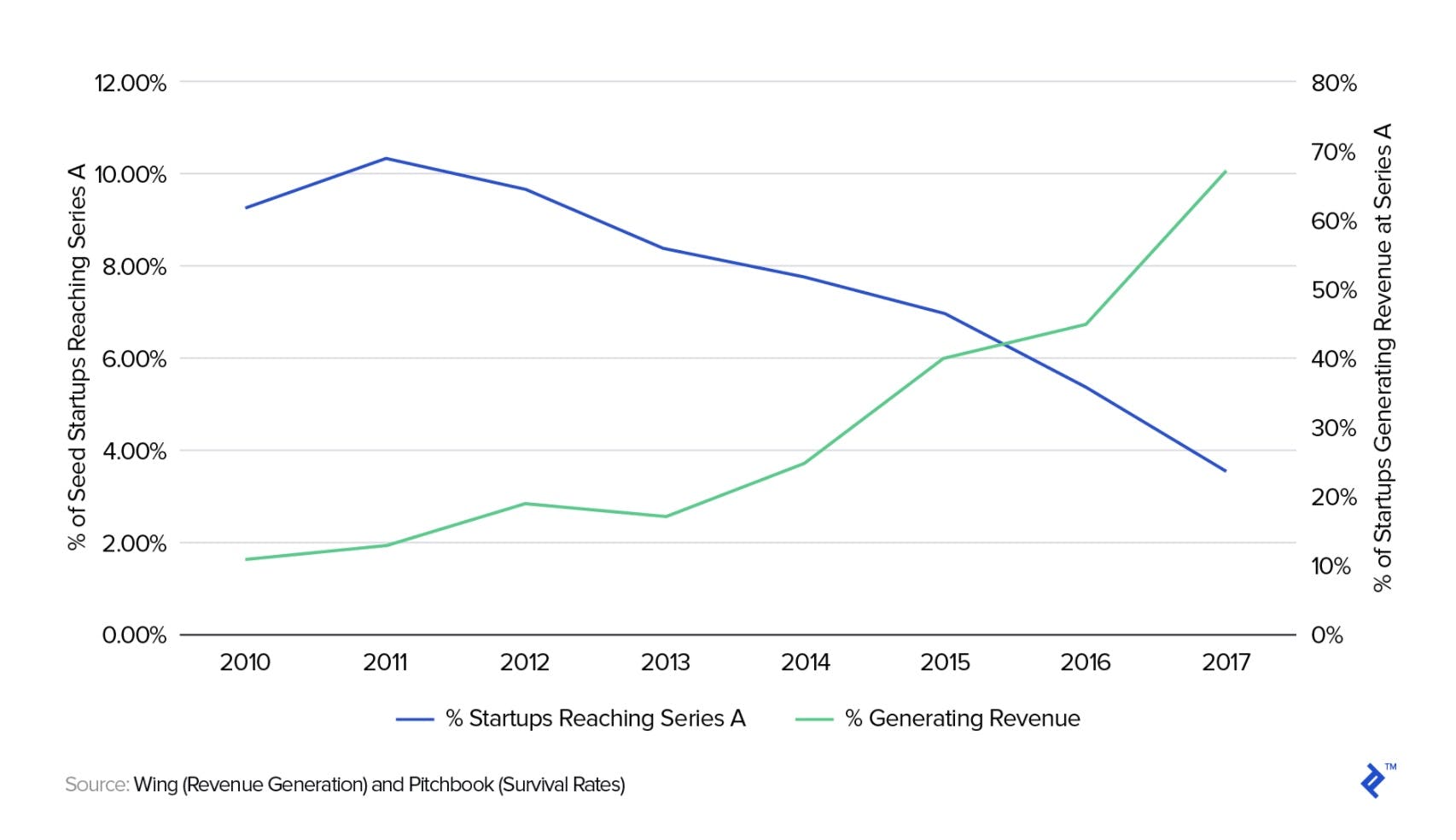

Between 2010 and 2017, the proportion of startups making it to Series A fell from 10% to less than 4%––and for those reaching Series A, 70% were generating revenue (compared to under 10% in 2010).

It will be even harder for these companies to get the amount of growth necessary to go public early, they will be even more capital intensive (incentivizing them to spend longer raising cheap money in the private markets), and they will have far more shareholders with liquidity needs than the lean software startups of the early 2000s.

The cost of building a company will continue to rise. Between 2009 and 2014, San Francisco real estate and payroll costs alone grew by 12% and 15% respectively.

At the same time, more predictable economics––based on sales, marketing, capex, and opex versus pure R&D––will make these companies an even more attractive investment for institutional investors hungry for yield.

So far, these trends––growing demand for private companies from institutional investors, bigger late-stage fundraising rounds and longer pre-IPO timelines––have fueled the growth of the private company secondary market from a few billion a year in 2010 to more than $30 billion a year in 2020.

As secondaries have gone from a marginal, side-line activity to a regular occurrence in Silicon Valley, so too has the market for private company liquidity solutions.

A brief history of the private company liquidity market

Dayton Carr, who founded Venture Capital Fund for America and started investing in secondary limited partner interests in 1982, is believed to be the first private equity secondary market investor in the United States.

Carr’s observation that secondary shares allowed investors to acquire valuable fund interests “later and cheaper” would soon become common knowledge, with Jeremy Coller at Coller Capital, Lexington Partners, Arnaud Isnard at ARCIS, and Stanley Alfeld at Landmark Partners starting their own secondary funds in the years that followed.

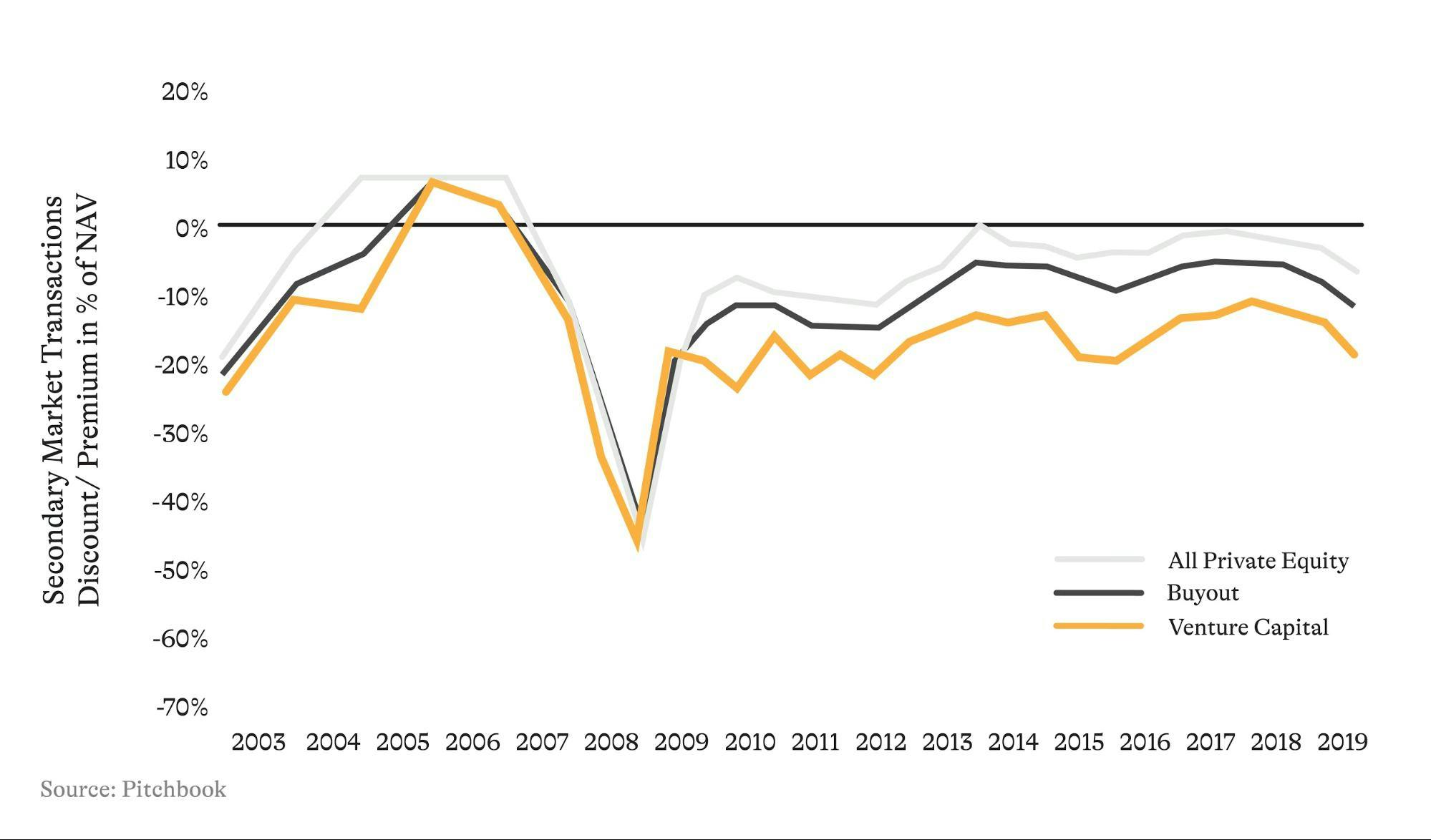

But secondaries would not become a massive market for decades. Transaction volumes in the private equity secondary markets went from less than $1B a year in 1997, to a little over $6B in 2003, to a record $88B last year.

The overall market for secondaries around the world has risen, like the market for direct company secondaries, in line with the explosion in private market financing––both buy-outs and venture.

The growth of the market for direct secondaries in private companies over the last several years has had a lot to do with a cultural shift in how startups and venture capitalists think about secondary sales.

A decade ago, venture capitalists and companies alike distrusted the idea of secondaries. Today, it is commonplace for founders to sell secondary as early as Series B, and in some cases earlier. Past the B, most primary rounds of fundraising include some secondary components.

Concurrently, the processes around running secondary sales have improved. Ten years ago, the secondary markets were known as a Wild Wild West, with employees of hot companies like Facebook selling shares at made-up prices to random investors.

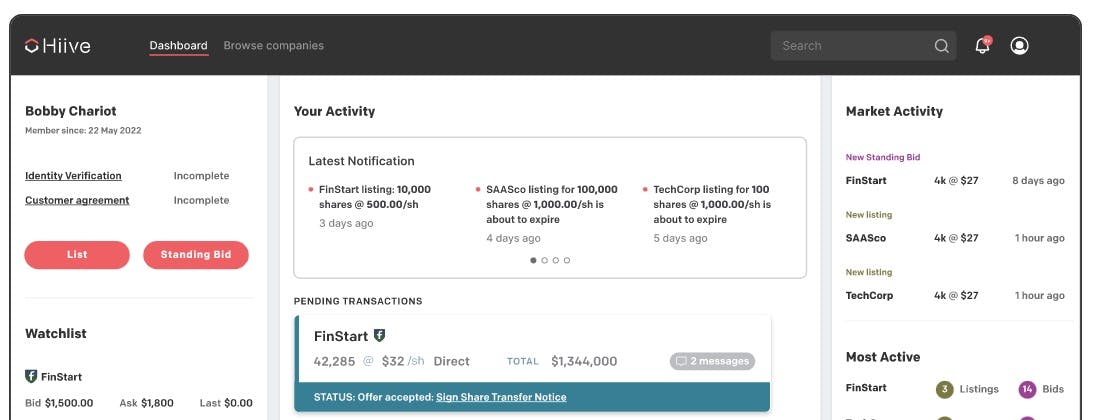

Today’s secondary market is far more sophisticated, if still nascent. While more open marketplaces still exist, transactions still must be issuer-approved and run through a more process. On the other side, issuer-controlled and structured liquidity programs allow companies to get liquidity on their own terms, carefully managing which employees and investors can participate.

1. Facebook, SecondMarket, and the Wild Wild West (2009-2012)

While services have existed to help investors transact in private company shares since the 90’s, the first two platforms built with secondary shares as the main focus—SecondMarket and SharesPost—both launched in 2009.

The secondary market for shares in Facebook was a flashpoint for the entire industry––and while it had a temporary chilling effect on secondary sales, it also helped lay the legal groundwork for the market we have today.

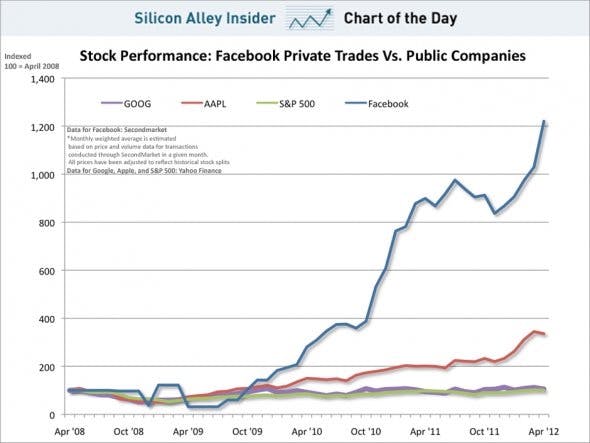

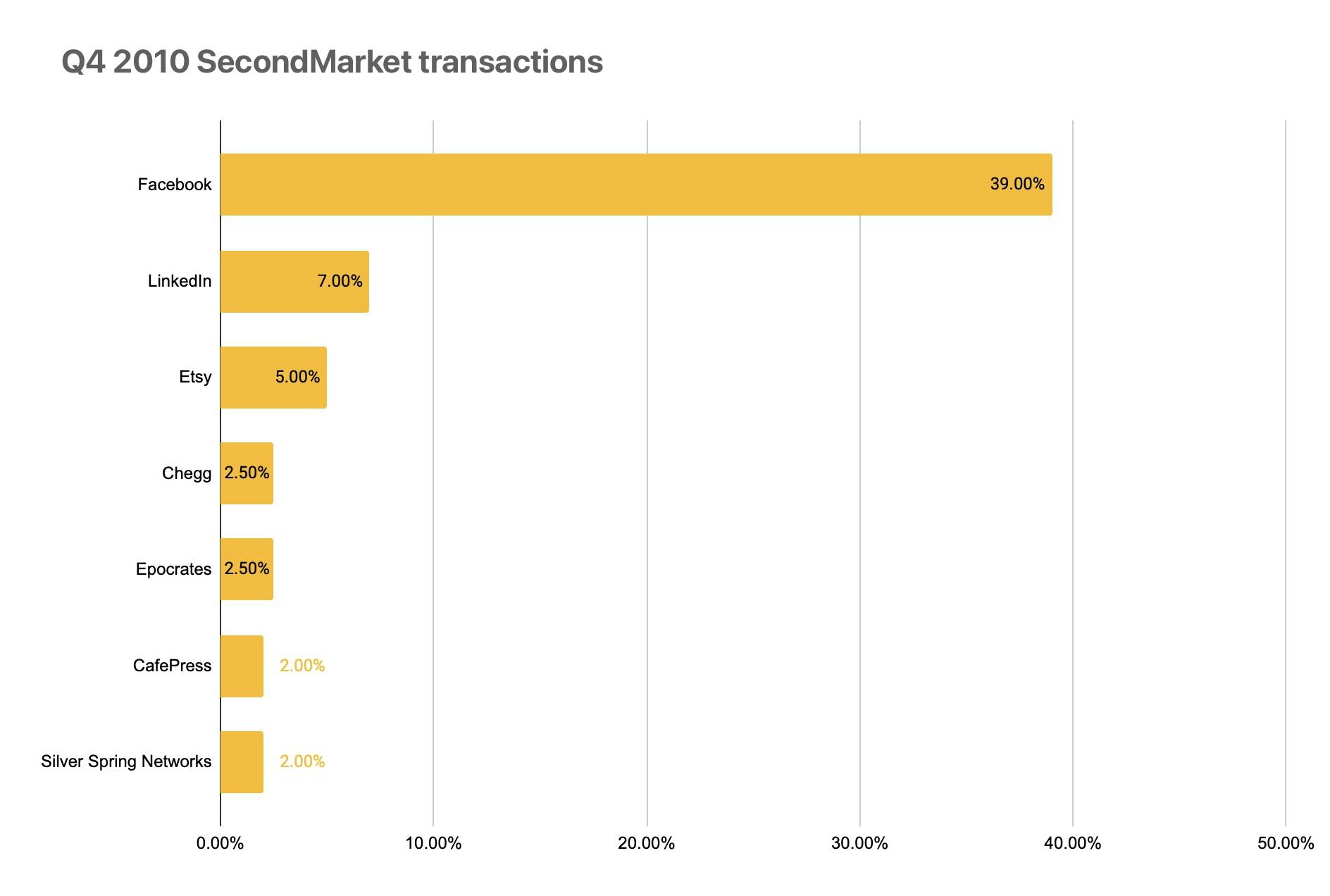

The majority of transaction volume for both exchanges through their first three years came from the stock of one company: Facebook. In the years leading up to Facebook’s IPO, shares of the company exploded in value on the secondary markets, surpassing shares of Apple and Google in value by April 2010.

Facebook's debut on the secondary markets and the resulting problems––wild pricing, thin trading, information asymmetries, and a lack of control––became an object lesson for issuers in how not to run a secondary market.

Participating were investors who had passed on the Series A (Kleiner), investors who had led previous rounds but wanted to increase their stakes (DST), and various pop-up funds, banks, and accredited investors, betting on growth.

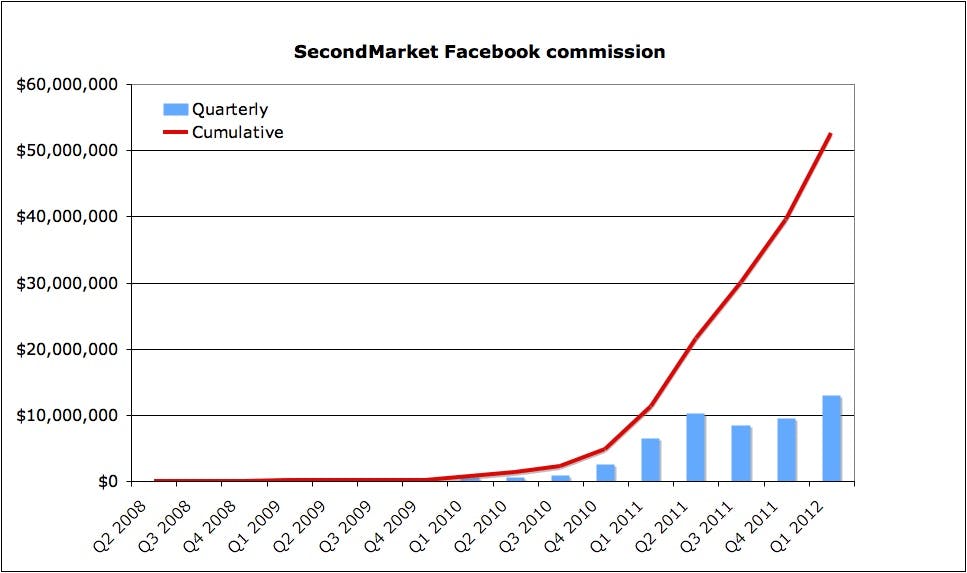

The “private-company exchanges” saw transaction volumes grow rapidly. SecondMarket went from facilitating $100M in transactions in 2009 to $360M in 2010 to $558M in 2011. Between 2010 and 2011, SharesPost doubled its transaction volume from about $300M to $625M.

Then came Facebook’s IPO.

Facebook’s value had soared on the secondary markets, pumped up by VC firms, banks, and others speculating on its future growth—and then it deflated. After a disastrous first, flat day, Facebook’s stock declined by 50% over its first four months in the market.

Facebook was such a popular stock on SecondMarket that it accounted for almost all of the volume on the platform in both 2010 and 2011.

Other private companies took notice, delaying their own IPOs, but also instituting various restrictions on secondary sales of stock, from insider trading rules to exorbitant transfer fees. Founders didn’t want their shares changing hands in the shadowy, anonymous secondary markets.

After the Facebook IPO, a 2014 Fortune survey found that most venture capital firms recommended banning secondary sales altogether until a liquidation event.

It wasn’t necessarily the concept of secondary sales itself that prompted the backlash from Facebook and others—it was the way that SharesPost and SecondMarket brokered transactions behind the backs of companies.

These exchanges came off as shadowy, and the entire secondary market for private company stock as a Wild Wild West, because they allowed startup employees to offload their shares to minimally vetted investors investing purely on speculation, with companies having no say in how often these transactions could happen, who could participate, and how much could be sold.

Because transactions took place between individuals without a true aggregating or exchange function in the marketplace, trading was thin and prices could swing wildly.

About 64 million shares of Facebook worth a cumulative $1.75 billion traded through SecondMarket before the company went public. Given SecondMarket’s 3-5% take rate, the company would have made somewhere in between $50 million and $87.5 million.

The result was a mess for public perception, pricing, the cap table, and existing shareholders, many of whom, in Facebook’s case, did not manage to capitalize on the hype and instead saw the value of their shares get cut in half.

Nor did trading Facebook shares wind up being a very good business for SecondMarket, either. We can reasonably estimate their total revenue from four years of facilitating a market for Facebook shares at about $50 million to $87.5 million––substantially lower than the $177 million that JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, and Facebook’s other underwriter reaped from the IPO in fees.

After Facebook’s IPO, SecondMarket would go on to lay off 40% of its staff and begin focusing on other, alternative asset classes––like wine. Transaction volumes there and at SharesPost cratered, though they began to recover back towards earlier levels by 2012. Meanwhile, a new batch of companies was getting started, aiming to avoid the same roadblocks that had gotten SecondMarket in trouble.

2. Forge, EquityZen, and the refactoring of the private-company exchange (2012-2015)

“We heard from the companies saying, ‘Quite frankly, (selling shares) should be outlawed because it’s so distracting. We don’t want anything like (what happened at Facebook) to develop and we’re looking at ways to change the bylaws in our businesses so it can be explicitly outlawed.’ Venture firms have said when founders are forming their companies, they’re (outlawing share sales) at that stage. That was when we realized a different solution was going to be required.“ —SecondMarket Founder & CEO Barry Silbert.

The hype around pre-IPO Facebook stock had proven that there could be a market for this kind of transaction, but it had also shown the problems in the current model for secondary transactions—problems to which companies in this space would spend the next few years trying out various solutions.

A big problem was control. Companies wanted to be able to manage the process of selling shares on the secondary market, from which employees were allowed to participate and how many shares each one was able to sell. They also wanted to make sure they weren’t adding investors they didn’t know or trust to their cap table.

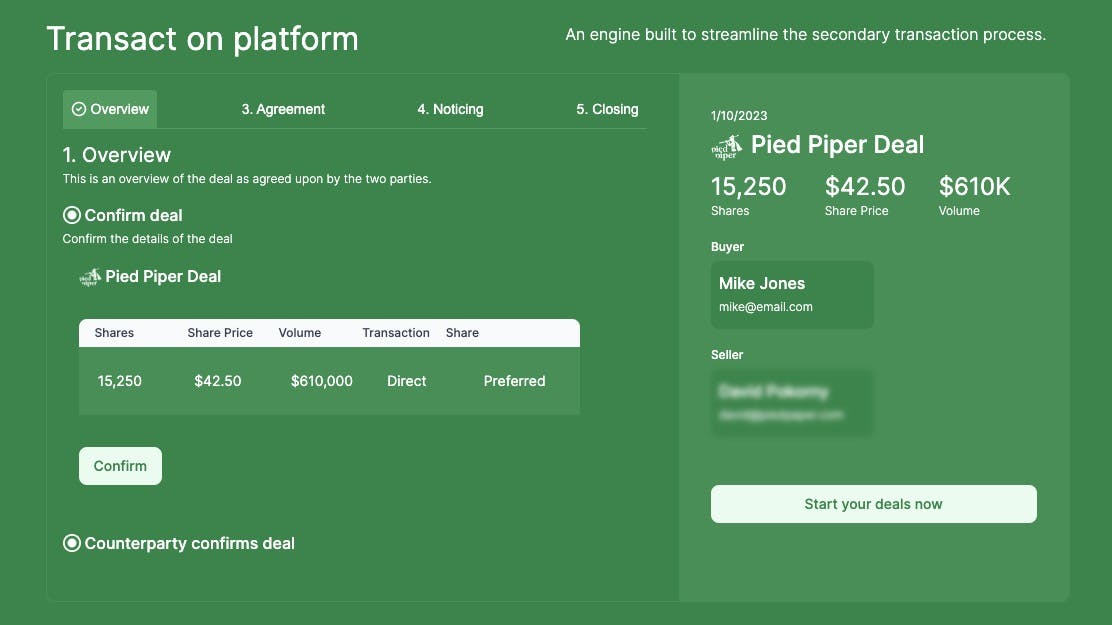

Another was logistics. Trading shares on the secondary markets means negotiating piles of physical stock certificates, cap table changes, ROFRs, restrictions on downstream ownership, and so on—a CFO’s nightmare. All in all, the process of exchanging shares between employee and investor can take anywhere from 3 to 6 months.

SharesPost, which started out as a bulletin board for startup employees and investors to meet up and negotiate an exchange, discovered this was a problem early on. More often than not, participants in their network wound up coming to SharesPost for help completing transactions.

While two banner years for the IPO market in 2013 and 2014 momentarily quieted appetites for secondary shares of stock, SecondMarket, SharesPost, and others began building new avenues through which private market liquidity might flow. In the process, they’ve developed distinct solutions to the problems of control and logistics—some issuer-centric, and some investor-centric—in handling secondary share transfers.

SecondMarket went the issuer-centric route, completely pivoting its business to helping companies set up private tender offers or “liquidity programs”—tailored, structured transactions between a select number of employees and a select number of vetted investors. Companies could run these liquidity programs in a completely customized way to give some liquidity to their employees and investors.

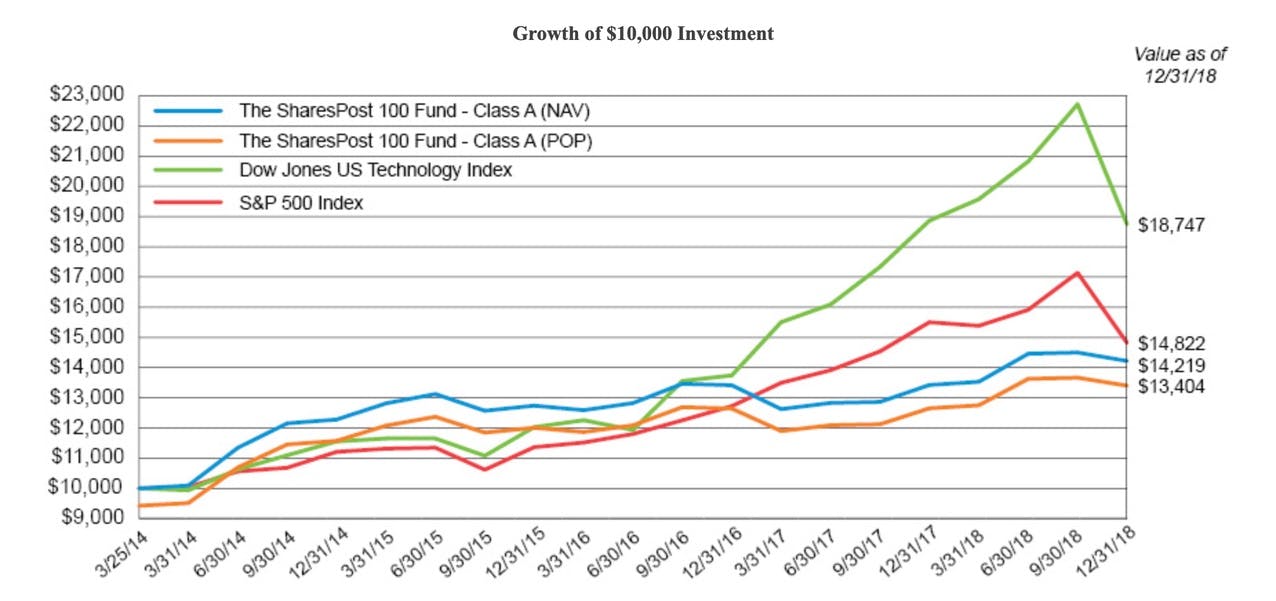

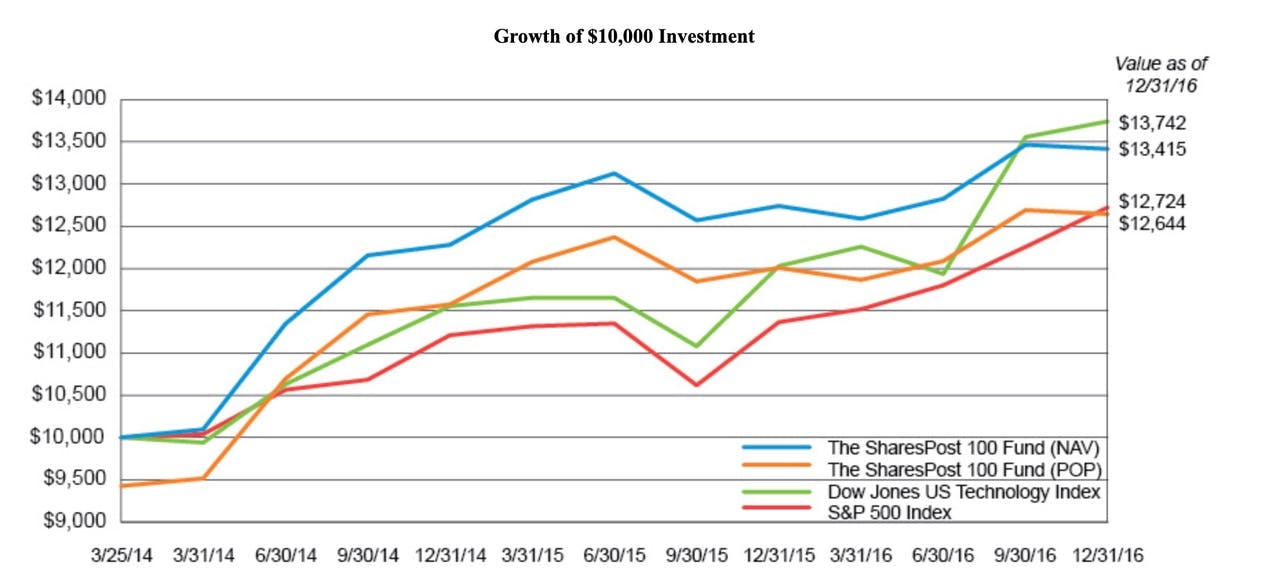

SharesPost went the investor-centric route, adding features like transparent bid/ask prices and research reports into the process and opening up the “SharesPost 100 Fund” to give investors a way to capture the upside on the growth of private companies without taking ownership of actual shares. While SharesPost made it possible for companies to halt trading, they did not mandate company participation.

The performance of the SharesPost 100 Fund varied through the years––between 2014 and 2016, it outperformed the Dow Jones US Technology Index and the S&P 500, while it underperformed between 2016 and 2018.

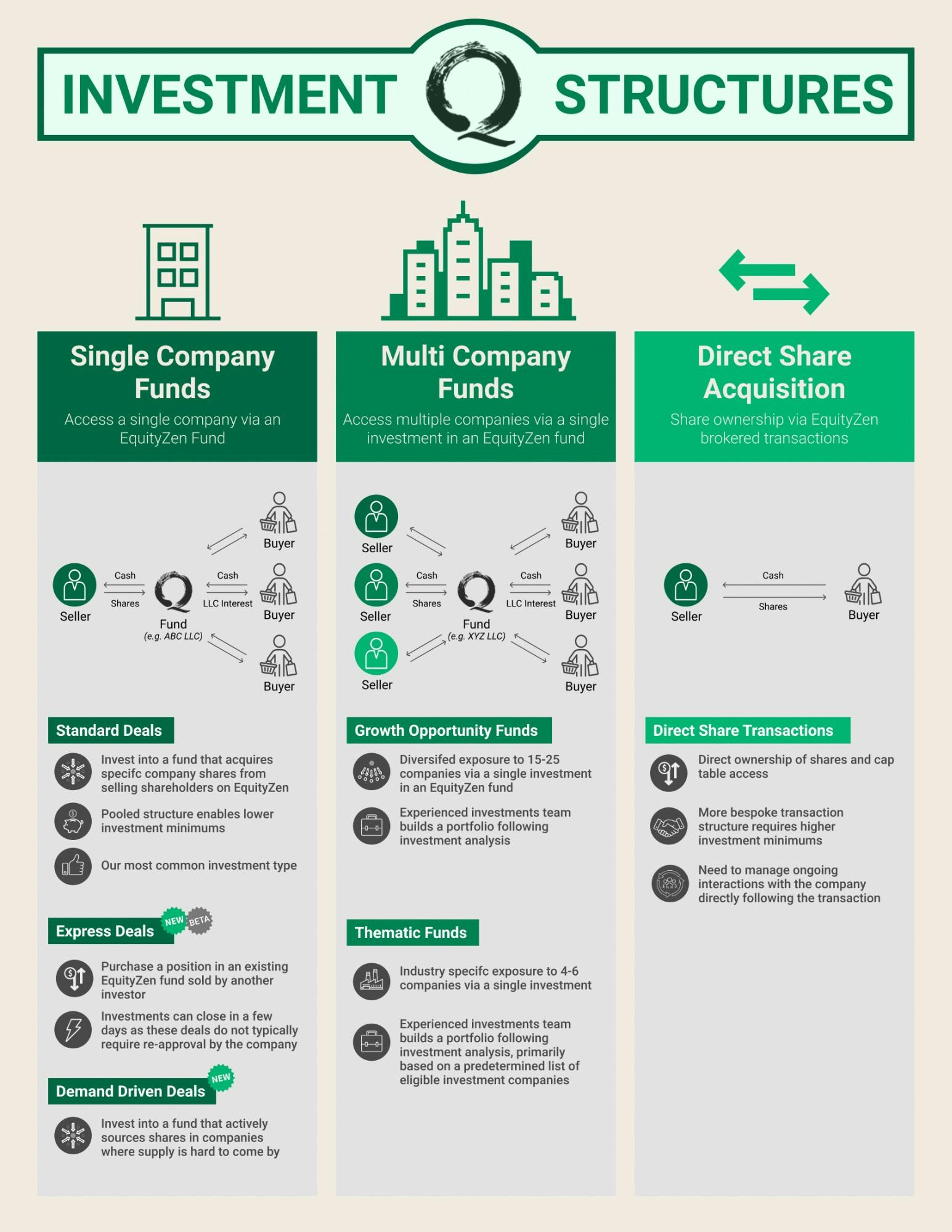

Other platforms that got started in these years sought to use derivative/swap and fund structures to accomplish approximately the same end goal as these marketplaces (giving companies access to liquidity and investors access to private companies) without needing to worry about the logistics of transferring shares.

Forge (formerly Equidate) was founded in 2013 with the idea that you help create liquidity in a way that eliminated the need for underlying share transfer entirely. Through forward contracts, investors could pay for the right to a shareholder’s shares upon exit—either through an IPO or an M&A. This allowed Forge to side-step all of the legal and financial complexities of transferring restricted stock, while at the same time introducing a few new types of complexities and risks—in particular, the risk that the company decides not to honor the terms of the contract at exit.

EquityZen also sought to avoid the complexity of transferring the underlying shares through a fund-based structure. Instead of employees selling shares to investors, employees sell their rights to the liquidity of those shares to EquityZen, who holds them in a fund until the company goes through an exit. Because of that LLC fund structure, only EquityZen ends up on the company’s cap table.

3. Nasdaq Private Market, Carta, and consolidation (2015-2020)

By 2015, the secondary market in private company shares had shifted.

Rather than being dominated by employee sales and individual-centric transactions, the company-sponsored tender offer had become the main driver of transaction volume.

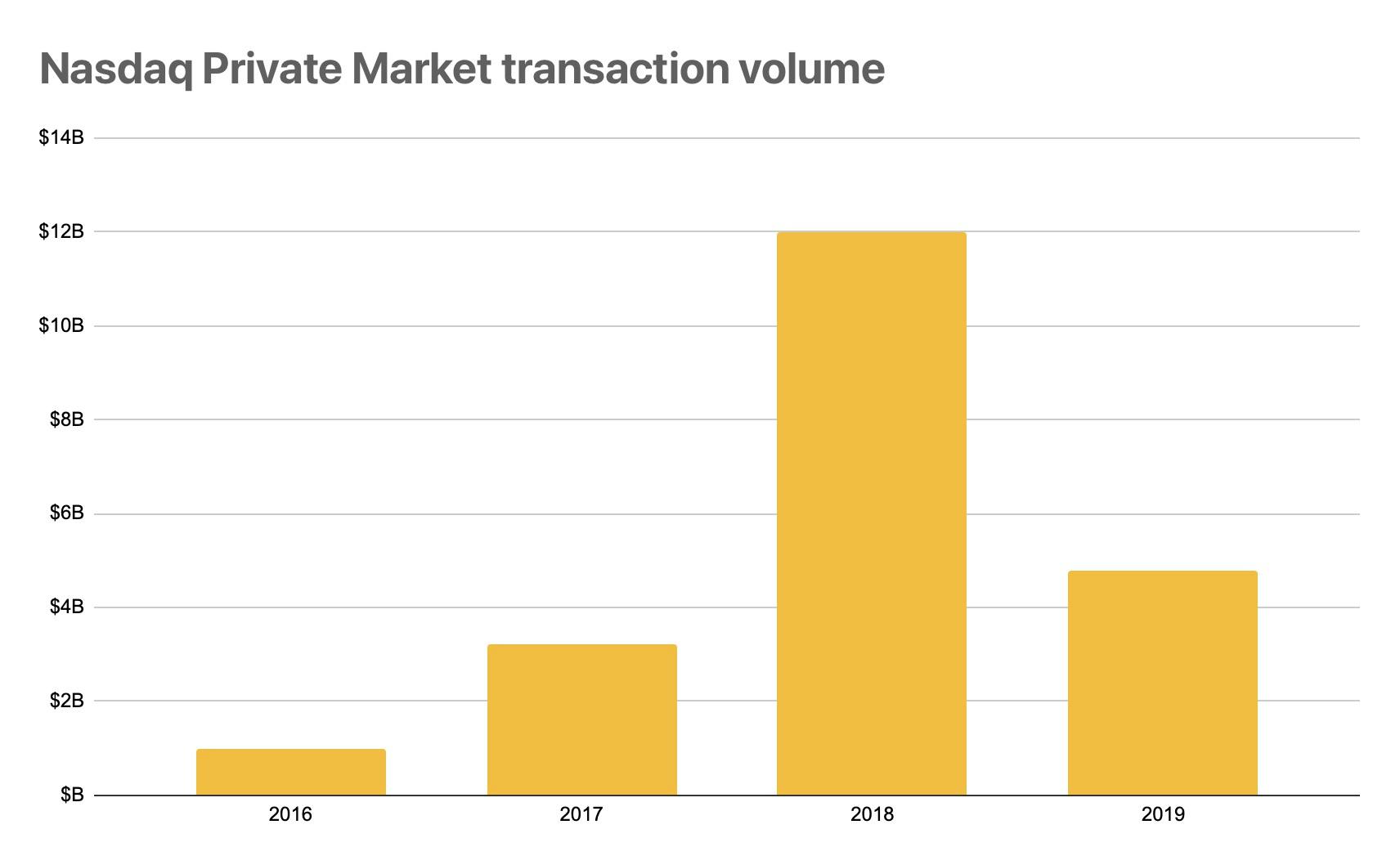

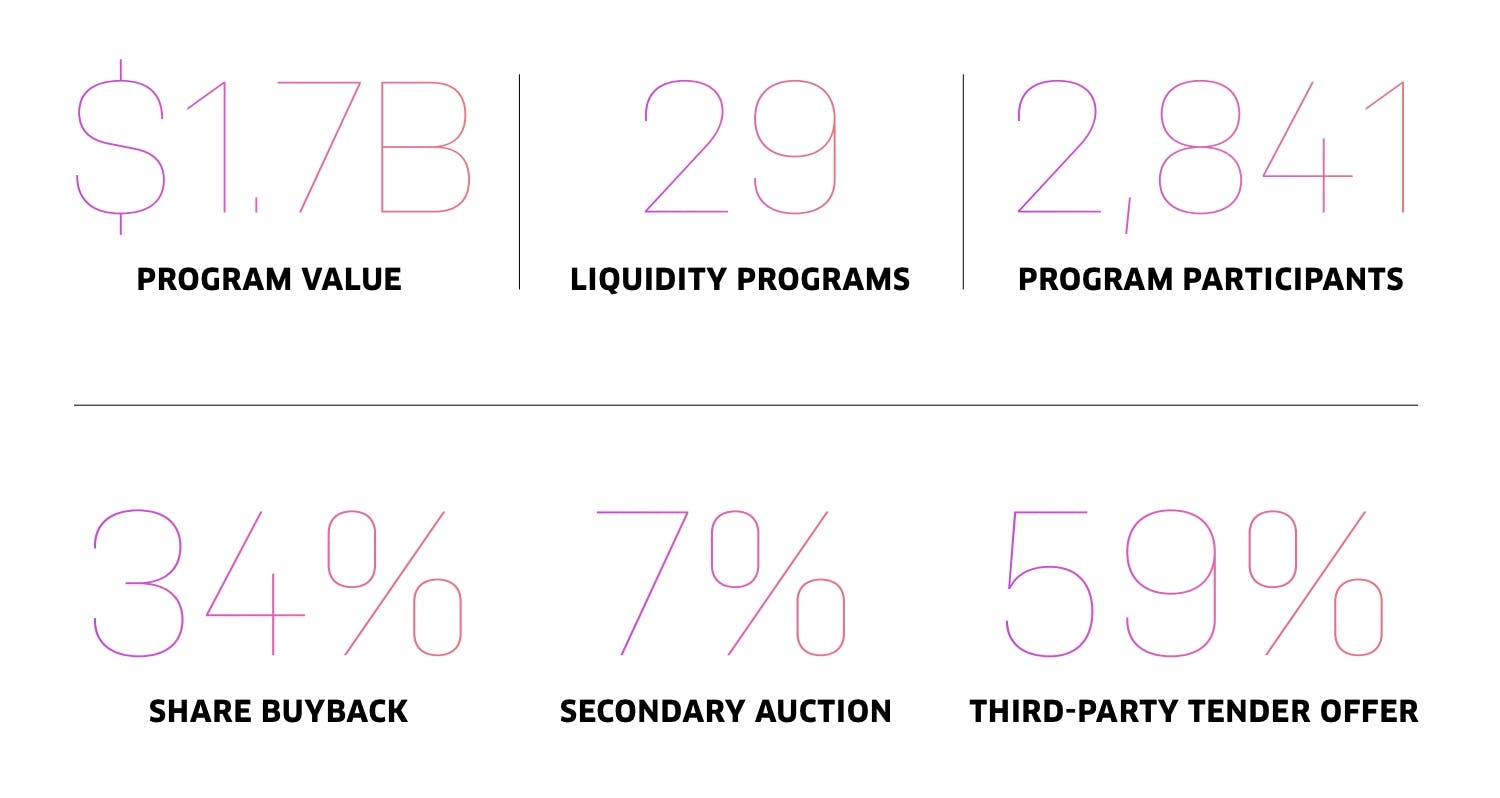

Nasdaq PM has steadily grown its transaction volume over the last several years (A greater than $12 billion secondary sale conducted by Uber drove up the average in 2018).

Today, the platform with the highest transaction volume in Nasdaq Private Market, which began as a joint partnership between Nasdaq and SharesPost before Nasdaq acquired SecondMarket in 2015. Nasdaq PM, which did about $4.8B in transaction volume through their platform in 2019, took SecondMarket’s technology and applied it to the use case of helping companies conduct tender offers.

With Nasdaq’s wide network of institutional investors, private placement agents, and advisors, they have the advantage of being able to tap into a deep pool of capital on the buy-side.

Utilizing a similar approach has been Carta, which will be launching its private marketplace CartaX later in 2020.

Carta, which manages the cap tables of about a third of all venture-backed private companies in the United States, has a unique advantage in having already made substantial progress building the private capital market rails essential to making secondary transactions frictionless.

Many of the complexities and costs involved in secondary transactions emerge directly out of the lack of a central repository for company shares. From dealing with restrictions on stock to physically transferring the shares to making sure the cap table accurately reflects all transactions, a lot of these problems can be solved when the transactions are done via a system of record for company equity. Solving them with software also makes it possible to turn liquidity events into a more frequent event—something that could completely reshape the way these events are perceived by issuers, employees, and investors alike.

The merger between Forge and SharesPost in May of 2020 that valued the latter at $160 million tells us that some much-needed consolidation is finally coming to the market for private company secondaries.

The fragmented nature of the market through its history has created poor liquidity as each platform competes for employees, investors and issuers. The general reliance on brokers to facilitate trades hasn’t helped, either, since brokers have a natural incentive to “shop” deals around to as many investors as possible, sometimes merely gathering information and interest versus genuinely selling shares that they own.

But not every entrant in this market is following the structured, company-centric listing model. ClearList, a subsidiary of the public market maker GTS, for example, is aiming instead to replicate the liquidity and autonomy of the public markets in the private markets from day one. Companies that list on ClearList will have their shares available for persistent trading within an open market, with GTS taking the other side of any transaction from the buy or sell-side.

The $225 billion addressable market for private company liquidity

While $30 billion a year in transaction volume is significant, there are trillions of dollars in equity value bound up, untapped, in the cap tables of the world’s venture-backed companies.

The total cumulative value of global unicorns alone is around $1.5 trillion as of 2020. Even if we suppose that companies only allow employees and investors to sell about 15% of their holdings per year, we still get a total addressable market for private company liquidity of $225 billion: about 7.5x the size of the market today.

We assume that most issuers would be willing to allow a cumulative 10-20% of their cap table to trade on the private markets.

Growth in this market has been constrained largely by the fact that buying and selling secondary is a time-consuming process that has not yet meaningfully scaled.

Most secondary sales today still take place via handshake deals and emails. Some are company-sponsored or at least company-informed, while others are initiated by brokers.

In this kind of opaque, decentralized market, brokers have the advantage of being able to see into both sides––and for doing the job of connecting buyers and sellers, they can collect hefty fees upwards of 7% per transaction (from both sides). These transactions are, however, plagued by informational asymmetries and perceptions of conflicts of interest.

Naturally, various disintermediating solutions have emerged to make this market more efficient, from marketplaces for pre-IPO stock like EquityZen and Forge to controlled liquidity program and tender offer products like Nasdaq Private Market.

None of the software platforms for secondary trading have yet been able to dethrone the one-to-one, broker-driven system by which most secondary sales are bought and sold.

The main challenge for these solutions has been that secondary markets are made up of several counterparties with different contexts and priorities:

- Employees have small blocks of stock and are highly motivated to sell due to the concentration risk of holding too much of their net worth in options.

- Investors have, or want to buy, large blocks––and they want to do so at the best price possible.

- Issuers, on the other hand, prize maintaining control of their cap table over all else.

Each platform fills a role in the ecosystem: platforms like EquityZen and Forge help exchange smaller, individual blocks of stock between investors and employees, and Nasdaq Private Market and Carta help late-stage privates create a secondary market for their shares before going public.

One of the challenges in building a centralized marketplace for private stock––which would guarantee a more liquid market––is that each distinct group of participants has different priorities and needs when transacting.

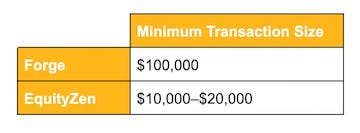

Marketplaces like Forge and EquityZen, with their hands-off and arms-length process, have an advantage when it comes to attracting individual employees who want to sell––and who therefore only need approval from their board or CFO––because they can make transactions happen relatively quickly. For these platforms, growing their network of institutional investors will be their main engine of growth.

Nasdaq PM and Carta, with their tender products, offer issuer control at the expense of speed and simplicity. Running a tender offer from start to finish can take up to 6 months––as long as your typical IPO prep process. There is a considerable investment of time, from the company, on working out the disclosures and risk factors of handling a tender.

One argument for an issuer-centric platform––one that puts control of liquidity firmly in the hands of companies––is simply that companies are ultimately the ones in control of their equity. Build a solution that doesn't work for them, and a critical mass will be unlikely to agree to it.

The upside is that companies can control who is going on their cap table and sell large blocks to both existing and new investors. For them, the core challenge is winning over demand from issuers and convincing them to run regular liquidity programs.

Because these different players have different core focuses, the growing market for private company liquidity is unlikely to be a winner-take-all one, at least in the short-term.

Common objections to the privately-traded model

When companies remain private, it cuts off the average American from accessing an increasing amount of value creation happening only in private markets

Short of forcing companies to go public once they hit a certain valuation, there’s little that can be done to push companies into the public markets.

What would be better would be to pull retail investors into the private markets. The SEC’s recent ruling on accreditation requirements is a positive step in this direction, but what’s needed to make quality private investment opportunities accessible to the everyday investor is a high-liquidity marketplace for buying and selling shares.

In 2019, the SEC began investigating a plan to allow retail investors to get access to pre-IPO companies through specialized funds, and companies like EquityZen have been giving their customers access to both actively managed and passive index funds in private companies for years.

More accessible liquid secondary markets pose a safety threat to everyday retail investors

While accessible markets do open up the possibility of retail investors losing money on investments, the same is true in the public markets. The everyday retail investor does not have the same access to information as a multi-billion dollar hedge fund.

The private markets do differ in that investments are generally illiquid, which is why liquidity is so important as a protection for investors: with sufficient liquidity, investors have the ability to exit trades instead of being locked in long-term.

Private companies will never make the disclosures necessary for this kind of market to operate and be liquid

Today, many of the biggest private companies already operate effectively like public companies in terms of disclosing information.

Uber, Facebook and Spotify all began disclosing comprehensive financials in the months and years leading up to their IPOs—to gain the trust of investors and demonstrate the strength of their businesses.

When companies become privately-traded, they’ll have to do the same to attract institutional investors that don’t have information rights and are fundamentally betting on the company’s economics and business model, and less so its product or vision.

The public markets are where companies become disciplined and set themselves up for long-term sustainability

In the years before it went public, Spotify allowed its stock to trade in the secondary markets every quarter. In exchange for giving team members and investors liquidity, and generating a pricing history that would become useful once the company direct listed into the New York Stock Exchange, Spotify made regular disclosures of its financial status and reported core KPIs, including free and paid user growth.

What Spotify’s case demonstrates is that even for the most well-known companies, establishing a liquid market for the shares of a privately held company will require companies to disclose.

Companies that wish to run a secondary sale once a year may have to disclose less than a company that runs them on a quarterly or monthly basis, but some degree of disclosures will be crucial nonetheless to generating investor demand––and that’s without the SEC getting involved.

The SEC is already discussing allowing unaccredited investors to participate in diversified pre-IPO funds in exchange for those pre-IPO companies disclosing more information, which means an SEC ruling establishing that private companies allowing more broad trading of their stock must disclose more information seems likely once liquidity in the secondary markets picks up.

How to build a privately-traded company: a guide for issuers

The privately-traded company is a powerful alternative to the status quo of total liquidity as a public company and zero liquidity as a private company.

Being privately-traded gives companies the ability to clean up their cap table and re-align with their investors, compete with public companies for the best talent, and build a more mature, disciplined business––all without facing the heightened disclosures and scrutiny of the public markets.

This guide will help you decide whether becoming a privately-traded company makes sense for your business, as well as help you think about the various challenges and decisions that go into creating a market for your privately-held stock, such as:

- Setting limits on who can buy and sell, and how much

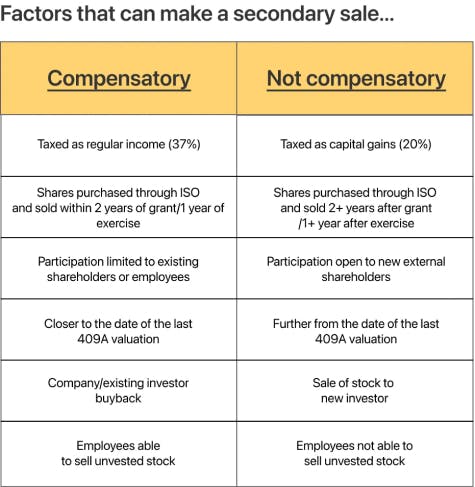

- Planning around the tax impact of sales as well as effects on your 409A valuation

- How establishing a private market can help you go public

Why companies get stuck between public and private

Once companies reach a certain size, they face a choice between two paths:

- Go public and accept the heightened scrutiny of public markets in exchange for a highly liquid market for their shares

- Stay private, minimize disclosures, but accept a degree of illiquidity that can make it difficult to recruit and retain team members

For a growing number of companies, neither path is ideal. Going public is no longer the prestige event that it was in the 1980’s or 1990’s, and it no longer serves the same purpose:

Companies today can raise hundreds of millions of dollars in the private market, and they don’t need an investment bank to introduce them to the world. And thanks to the JOBS Act of 2012, the shareholder limit that forced both Facebook and Google to go public is no longer an issue for most companies.

Meanwhile, private companies are using that cash to build increasingly durable, mature, businesses, and they’re doing so while retaining total control over their own narrative and insulating themselves from the volatile public markets.

That means they can set aside short-term, quarterly earnings and focus on their long-term mission, whether it’s colonizing Mars (SpaceX) or re-building the payments infrastructure of the internet from the bottom-up (Stripe).

The problem is liquidity.

Over time, employees and investors who have deployed either their labor or their capital in exchange for equity in your company begin to expect some kind of return. Funds have a life cycle of 12 years or so, and VCs raise a new one every 2-3 years––the median tenure for startup employees is just 2 years.

The longer you stay private, the more vested equity you have building up on your cap table, and the more pressure there’s going to be to go public––because you’re no longer aligned with your shareholders, and an IPO generally is the easiest way to re-align.

The third path: the privately-traded company

Becoming a privately-traded company is about using controlled liquidity, not an IPO, to re-align yourself with your employees, with your investors, and with the market as a whole.

The misalignment created by illiquidity is gradual. Employees, who might hold most of their net worth in equity but don’t see an exit event coming on the horizon, start thinking about leaving. Investors, who have seen their investment 10x but are getting close to the end of their fund lifecycle, find they start needing to return capital to their LPs.

Fortunately, this misalignment can also be reversed through the controlled deployment of liquidity through secondary sales.

Align with investors by refreshing your cap table

Misalignments with investors can result in a wide variety of negative outcomes: selling too early, not selling when selling would be the optimal outcome, taking on systemic risks, trying to grow too fast, going public too early.

By building a marketplace for their stock while still private, CEOs gain three vital tools for correcting misalignments with investors, avoiding these kinds of outcomes, and building a stronger business:

- Rebalancing the cap table: Investors can take 10-20% of their returns off the table, allowing them to return some capital to LPs or raise a new fund while sticking around for the long-term

- Refreshing the cap table: Early stage investors whose skill sets no longer match the needs of the business can get their exit and make more room for other investors

- Replacing the cap table: New investors with strategic importance (e.g. for a new distribution strategy or in anticipation of an IPO) can be brought onto the cap table without creating dilution

Key to the liquidity program’s power is the fact that investors can modify their exposure in real time. Depending on their specialization and where they are in their current fund’s lifecycle (as well as any other funds they might be raising), different sets of investors will have different ideas about what kind of business you’re building, when it might make sense to sell or go public, and how long they’re willing to wait for either outcome.

With the power to “rebalance” their portfolio, investors can take just enough off the table to satisfy their need for liquidity and get re-aligned for the long-term.

In other cases, a CEO might want to get an earlier, misaligned investor off the cap table entirely.

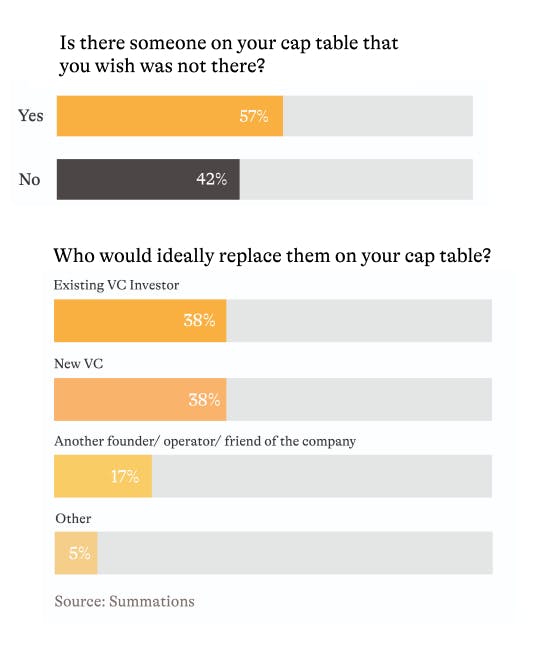

Of 100 founders surveyed by Flex Capital on secondary sales earlier this year, more than half said that they currently had people on their cap table that they wished they were not there. More than half said they would prefer their place on the cap table be taken up by a new VC or another friend of the company/fellow operator.

There are multiple reasons a founder might want to switch out investors and bring other ones on. One investor might have come in at the seed stage, and might have been asking for some time about the possibility of liquidating some of their shares. Their expertise might be primarily useful for earlier-stage companies, and so their value to the company may no longer be as high. And a company planning to go public in the near future might want to bring on a larger institutional investor like Fidelity or T. Rowe that can help support the IPO.

Ultimately, companies can live or die on whether or not their investors want or need liquidity. A controlled liquidity program makes it possible for a company to fit better into the economics of VC, and that means better alignment between CEOs and investors—and better long-term odds for everyone.

Align with employees by providing periodic liquidity

After Fairchild Semiconductor, it became normal for companies in Silicon Valley to offer employees stock options. But employee equity has become broken in many ways.

In 1999, technology companies took about 4 years to go public. In 2020, the median technology company going public takes more than 11.5 years. And many of the most valuable ones are already close to or above that threshold:

- Stripe: 10

- Airbnb: 12

- UiPath: 15

- Tanium: 13

- Palantir: 17

- SpaceX: 18

- Automattic: 15

- Epic Games: 29

When companies stay private this long, it can throw them out of alignment with employees and create substantial retention and recruiting challenges.

Illiquid compensation is the core problem. After the typical 4-year vesting period and any refresh grants they receive afterwards, an employee might hold a big portion of their net worth in their employer’s restricted stock. Without the means to sell any of that stock, however, the gains remain on paper.

Employee discussions on sites like Blind and Glassdoor make clear that many recruits no longer attribute value to the options or RSUs they get from a prospective private employer—they value them at $0.

What makes this illiquidity all the more frustrating, but ultimately an asymmetric advantage if your company employs a liquidity program, is the way that valuations rise so quickly in the private markets. Employees can become paper millionaires years before they have any chance of seeing a real return.

With a liquidity program that allows them to sell 10-20% of their stock every year, however, those same employees can potentially be getting huge off-balance-sheet bonuses that make their compensation competitive with some of the best (public) companies out there.

Some CEOs fear that giving out liquidity to employees will hurt their long-term commitment to the business, but the truth is the reverse. By letting them relieve some pressure on their finances through a controlled liquidity program, companies can get their best talent to double down—rather than taking their skills somewhere that they can get liquidity for their shares.

When companies stay private for as long as they do nowadays, employees go through many of the same life stages that founders do while still illiquid—buying a house, getting married, dealing with sickness, and so on.

Without liquidity, employees who want to take one of these big steps in life are faced with nothing but bad choices:

- Stay illiquid, hold on for exit, and accept the risk creep that comes with being so undiversified

- Leave, spend tens of thousands of dollars if not more to exercise a set of uncertain options

- Leave, return the options, and lose out on the value that you’ve built up over the years of work

With liquidity, employees can turn a small amount of their stock into cash that can help handle some of these kinds of life events, and then return to the business of making the company successful over the long-term. After all, they still are going to have a substantial portion of options after selling 10%—they just won’t have as huge a concentration risk.

Align with the market by allowing progressive price discovery

Creating liquidity for your stock in the private markets allows for better price discovery. While a conventional view is that investors and founders and employees all benefit from illiquidity because it generates higher valuations, more efficient pricing is better for businesses in the long-run.

That means more opportunities to buy and sell stock, but it also means fostering more openness and transparency around the state of the business as you grow, and sharing information with not just internal stakeholders but the public.

Today, a private company’s stock tends to get repriced once every 1-2 years. That repricing is largely the domain of the company’s lead investor, which has a strong incentive to not create a perception of weakness with a down round, which means valuations naturally tend to rise over time.

Liquidity is more than a way to improve your compensation plans––in the hands of a strategic CFO, it is a powerful tool that unlocks M&A opportunities, can lower your cost of capital, and more.

They don’t rise gradually, either. In many cases, startups are on forced marches upwards, and those sudden step-function valuation jumps can end up coming back to hurt companies.

It’s impossible to know for sure whether WeWork or Zenefits could have been a sustainable company without the huge expectations foisted upon them by their huge valuations, but they didn’t help.

For companies like Snapchat and Uber, some better price discovery before IPO might have helped temper expectations and avoid the bad reputation that comes with a sagging stock price.

If a company does want to go public, secondary sales prior to listing have already proven effective at establishing a market price and preparing a company for the transition.

A year before iHeartRadio went public, the price of the stock had hung in a $15-19 range while trading on the Pink Sheets OTC market. When the company listed on NASDAQ in 2019, it ended its first day of trading right in the middle of that range at $16.50 a share.

Over the three months preceding Spotify’s IPO, 7.8M+ shares of Spotify changed hands on the secondary markets, with Equidate alone handling $150M worth of transactions. Spotify ran liquidity events at a rate of one per quarter according to John Buttrick at Union Square Ventures. Each liquidity event was made open to all existing holders of the company’s stock, including employees, executives, and investors.

Spotify also began doing quarterly shareholder calls a few years before it went public, disclosing information to shareholders about their business and financials.

Running these events allowed Spotify to demonstrate the market’s interest in their stock, set a precedent for the price they chose when they listed on the stock exchange, and got the company accustomed to making regular disclosures.

In the end, Spotify’s reference price was set at $132—just below the highest per-share secondary sale price during 1Q 2018. The company employed market maker Citadel Securities to help build an order book for the first day of trading. The stock would go on to close its first day at about $149.

Both Spotify and iHeartRadio, in effect, used secondaries to bridge the gap between the private and public markets. In both cases, using secondaries for price discovery also made it more possible to direct list, enabling them to go public without an IPO underwriter setting their price.

How to design a liquidity program

Becoming a privately-traded company is like building your own internal stock market.

A market is a complex organism, and it’s important that you design the structure of the liquidity program meaningfully, with the right parameters and limits––otherwise, you can easily lose control.

Auctions for secondary shares of Facebook traded weekly with very little oversight between 2010 and 2011. Employees rushed to liquidate shares of the seemingly-overvalued company. Shares traded at rapidly changing prices, resulting in a flood of random shareholders on the Facebook cap table. One employee was fired for insider trading, while the SEC charged several funds with fraud for their involvement in the market.

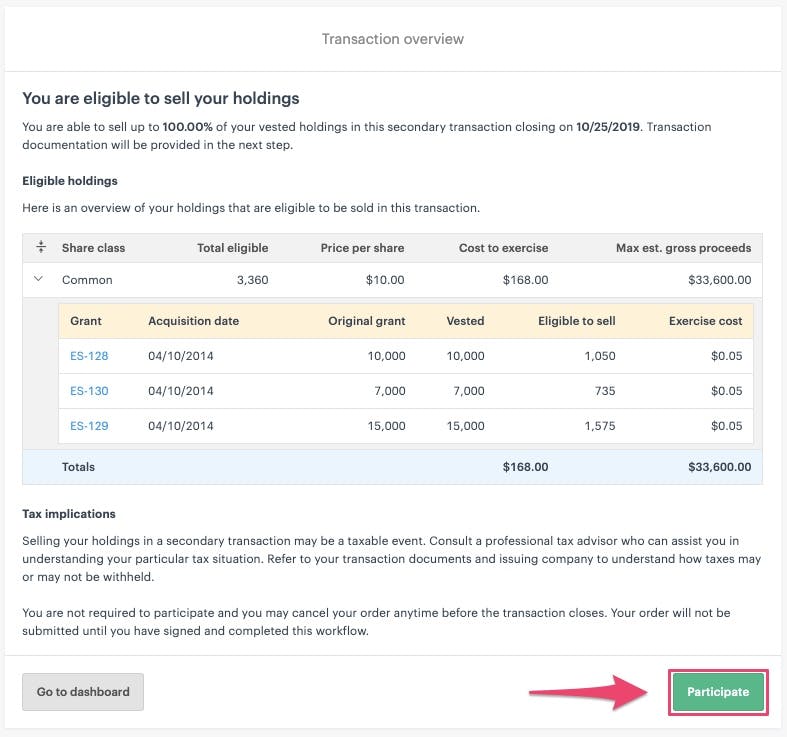

Since Facebook, virtually all venture-backed companies have instituted strict restrictions on who can sell secondary, when they can sell it, and to whom. At some companies, employees aren’t allowed to sell secondary at all.